Maureen Letostak

(202) 205-2603

Maureen.Letostak@usitc.gov

To view changing data, hover over or touch the animated graphic below.

To view changing data, hover over or touch the animated graphic below.Change in 2017 from 2016:

- U.S. total exports to the United Kingdom: increased by $1.0 billion (1.9 percent) to $56.3 billion

- U.S. general imports from the United Kingdom: decreased by $1.2 billion (2.2 percent) to $53.1 billion

- U.S. trade surplus with the United Kingdom: increased by $2.2 billion (220.0 percent) to $3.3 billion

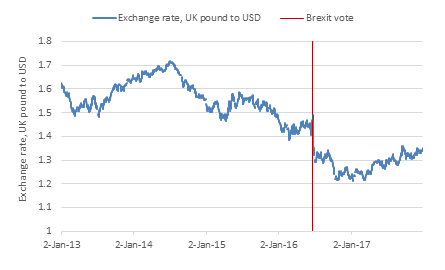

In a referendum held on June 23, 2016, 51.9 percent of the participating United Kingdom (UK) electorate voted to leave the European Union (EU). The UK is set to officially withdraw from the EU in March 2019, with a 21-month transition period lasting through December 2020.[1] This departure from the EU is also known as “Brexit.” While the impact of Brexit on the U.S. economy is still largely unknown, some immediate effects have been noticeable. Following the vote, the British pound fell against the U.S. dollar.[2] And while the pound’s value increased overall throughout 2017, it has yet to return to pre-vote levels (figure UK.1). This 2017 rise in the pound’s value boosted the competitiveness of U.S. exporters in 2017,[3] which may explain, at least in part, the increase in U.S. exports to the UK between 2016 and 2017.

Figure UK.1: Exchange rate of the UK pound sterling to U.S. dollars, 2013–17

Source: Federal Reserve. Foreign Exchange Rates. Table H.10 (accessed May 6, 2018).

Inflation in the UK after Brexit increased to a yearly rate of 3.1 percent by the end of 2017, its highest level since 2012. This subsequently caused a slowdown in consumer spending and economic growth.[4] The unemployment rate declined throughout 2016 and 2017, while wage growth reached its peak in the fourth quarter of 2016.[5]

U.S. Total Exports

U.S. total exports to the UK increased by $1.0 billion (1.9 percent) to $56.3 billion in 2017. Despite a large decline in U.S. transportation equipment sector exports (down $1.7 billion), the value of U.S. total exports rose overall due to increases in exports of both energy-related products (up $2.0 billion) and minerals and metals (up $967 million).

Table UK.1: United Kingdom: U.S. total exports, general imports, and merchandise trade balance, by major industry/commodity sectors, 2013–17

|

Million $

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item |

2013

|

2014

|

2015

|

2016

|

2017

|

Absolute change,

2016–17

|

Percent

change,

2016–17

|

| U.S. total exports: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Agricultural products |

1,888

|

1,975

|

2,083

|

2,077

|

1,918

|

-159

|

-7.6

|

| Forest products |

1,583

|

1,761

|

1,896

|

1,745

|

1,696

|

-49

|

-2.8

|

| Chemicals and related products |

7,103

|

7,553

|

8,997

|

8,022

|

7,498

|

-524

|

-6.5

|

| Energy-related products |

2,484

|

2,606

|

2,334

|

1,769

|

3,760

|

1,990

|

112.5

|

| Textiles and apparel |

665

|

665

|

695

|

647

|

661

|

14

|

2.2

|

| Footwear |

35

|

24

|

24

|

22

|

29

|

7

|

29.7

|

| Minerals and metals |

5,311

|

7,655

|

7,360

|

7,303

|

8,269

|

967

|

13.2

|

| Machinery |

3,338

|

3,968

|

3,809

|

3,735

|

3,860

|

124

|

3.3

|

| Transportation equipment |

12,326

|

13,901

|

14,790

|

16,046

|

14,372

|

-1,675

|

-10.4

|

| Electronic products |

6,549

|

7,120

|

7,083

|

6,743

|

6,723

|

-21

|

-0.3

|

| Miscellaneous manufactures |

4,149

|

4,448

|

4,452

|

4,737

|

4,983

|

246

|

5.2

|

| Special provisions |

1,930

|

2,236

|

2,572

|

2,440

|

2,559

|

118

|

4.9

|

| Total |

47,361

|

53,913

|

56,095

|

55,289

|

56,329

|

1,040

|

1.9

|

| U.S. general imports: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Agricultural products |

2,561

|

2,645

|

2,629

|

2,778

|

2,830

|

53

|

1.9

|

| Forest products |

556

|

624

|

622

|

627

|

667

|

40

|

6.5

|

| Chemicals and related products |

8,665

|

9,411

|

13,960

|

11,338

|

9,364

|

-1,973

|

-17.4

|

| Energy-related products |

7,998

|

6,286

|

4,006

|

3,247

|

3,242

|

-5

|

-0.2

|

| Textiles and apparel |

405

|

457

|

460

|

422

|

390

|

-32

|

-7.7

|

| Footwear |

30

|

33

|

31

|

28

|

24

|

-4

|

-14.7

|

| Minerals and metals |

3,332

|

3,835

|

3,079

|

2,990

|

2,976

|

-15

|

-0.5

|

| Machinery |

3,998

|

4,239

|

4,129

|

3,732

|

3,835

|

103

|

2.8

|

| Transportation equipment |

12,988

|

14,106

|

14,836

|

15,432

|

15,855

|

423

|

2.7

|

| Electronic products |

5,445

|

5,572

|

5,596

|

5,441

|

5,490

|

49

|

0.9

|

| Miscellaneous manufactures |

2,393

|

2,395

|

2,839

|

2,476

|

2,914

|

438

|

17.7

|

| Special provisions |

4,369

|

5,088

|

5,805

|

5,761

|

5,488

|

-273

|

-4.7

|

| Total |

52,741

|

54,689

|

57,993

|

54,272

|

53,075

|

-1,197

|

-2.2

|

| U.S. merchandise trade balance: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Agricultural products |

-673

|

-669

|

-546

|

-701

|

-912

|

-211

|

-30.2

|

| Forest products |

1,028

|

1,137

|

1,274

|

1,118

|

1,029

|

-89

|

-8.0

|

| Chemicals and related products |

-1,562

|

-1,858

|

-4,963

|

-3,315

|

-1,866

|

1,449

|

43.7

|

| Energy-related products |

-5,515

|

-3,680

|

-1,672

|

-1,478

|

518

|

1,996

|

(a)

|

| Textiles and apparel |

259

|

208

|

235

|

225

|

272

|

47

|

20.7

|

| Footwear |

5

|

-8

|

-7

|

-6

|

5

|

11

|

(a)

|

| Minerals and metals |

1,978

|

3,820

|

4,282

|

4,312

|

5,294

|

982

|

22.8

|

| Machinery |

-660

|

-271

|

-320

|

4

|

25

|

21

|

571.3

|

| Transportation equipment |

-662

|

-205

|

-46

|

614

|

-1,483

|

-2,098

|

(a)

|

| Electronic products |

1,104

|

1,548

|

1,486

|

1,302

|

1,233

|

-69

|

-5.3

|

| Miscellaneous manufactures |

1,755

|

2,054

|

1,612

|

2,262

|

2,070

|

-192

|

-8.5

|

| Special provisions |

-2,439

|

-2,852

|

-3,233

|

-3,321

|

-2,929

|

392

|

11.8

|

| Total |

-5,380

|

-776

|

-1,898

|

1,017

|

3,254

|

2,237

|

220.0

|

Source: Compiled from official statistics of the U.S. Department of Commerce.

Note: Import values are based on customs value; export values are based on free along ship value, U.S. port of export. Calculations based on unrounded data. Sectors are ordered by the level of processing of the products classified therein.

aNot meaningful for purposes of comparison.

U.S. exports of energy-related products accounted for the largest increase in U.S. exports to the UK (up $2.0 billion, or 112 percent). This increase is almost completely due to the growth in U.S. exports of crude petroleum, which surged by $1.8 billion (762 percent) to $2.1 billion in 2017. The increase appears to reflect two important developments: it followed the removal of U.S. restrictions on exports of crude petroleum in December 2015[6] and an increase in U.S. crude petroleum production by more than 384,000 barrels per day in 2017.[7] In 2017, the UK was the United States’ third-largest export market for crude petroleum after Canada and China, though it accounted for only 9 percent of exports. The U.S. was the second-largest supplier, after Norway, of crude petroleum to the UK in 2017.[8]

U.S. exports of bituminous coal[9] to the UK increased $166 million (196 percent) from 2016 to 2017. Between 2016 and 2017, U.S. exports of thermal coal to the UK increased by $103 million (2,738 percent); of metallurgical coal, by $62 million (77 percent). While UK consumption of coal has continued to decline[10] as the UK moves toward more environmentally friendly forms of energy, coal production has fallen faster than coal consumption in the UK, which has increased the UK’s need to import coal to supply its remaining coal-powered plants.[11] In 2017, U.S. coal accounted for one-third of the UK’s imports of bituminous coal.[12]

U.S. total exports to the UK in the minerals and metals sector increased by $967 million (13.2 percent), rising from $7.3 billion in 2016 to $8.3 billion in 2017. Over half of U.S. exports to the UK in this sector were in unrefined and refined gold,[13] specifically nonmonetary gold bullion, which accounted for $844 million of the $967 million increase. This increase can be attributed to the global increase in gold prices from 2016 to 2017.[14] The value of U.S. exports of gold to the UK has continued to rise since 2013.

While U.S. total exports to the United Kingdom grew in over half the industry sectors, U.S. exports of transportation equipment declined by $1.7 billion (a drop of 10.4 percent); U.S exports of transportation equipment, the largest export sector, accounted for 25.5 percent of U.S. total exports to the UK in 2017. Most of this decline ($1.6 billion) was in exports of goods that fall within the aircraft, spacecraft, and related equipment sector.[15] Aircraft represents the largest HS 2-digit export category to the UK from the United States (HS 88 went from $11 billion to $9.4 billion). Nearly all of this decline was in civilian aircraft ($10.6 billion to $9.1 billion). This decline in U.S. exports in 2017 largely offset an increase in this sector that occurred between 2015 and 2016. Though the UK does not produce entire civilian aircraft, the UK aerospace industry is the second largest in the world, following the United States.[16]

U.S. General Imports

U.S. general imports from the UK decreased by $1.2 billion (2.2 percent) to $53.1 billion in 2017. This decline is attributable in large part to a decline in imports of chemicals and related products ($2 billion), which more than offset increases in the miscellaneous manufactures and transportation equipment sectors ($438 million and $423 million, respectively). Thirty percent (over $15.85 billion) of U.S. general imports from the UK came in the transportation equipment sector in 2017, of which a substantial part were vehicles. U.S. imports of vehicles (for both consumer and commercial use) from the UK (HS 87) also declined slightly, going from $9.7 billion in 2016 to $9.64 billion in 2017. In addition, close to 20 percent ($9.36 billion) of U.S. general imports from the UK came in the chemicals sector.

Table UK.2: United Kingdom: Leading changes in U.S. exports and imports, 2013–17

|

Million $

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item |

2013

|

2014

|

2015

|

2016

|

2017

|

Absolute change,

2016–17

|

Percent

change,

2016–17

|

| U.S. total exports: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Increases: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Energy-related products:

Crude petroleum (EP004)

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

238

|

2,057

|

1,818

|

762.4

|

|

Coal, coke, and related chemical products (EP003)

|

1,132

|

746

|

313

|

85

|

257

|

171

|

200.5

|

|

Precious metals and non-numismatic coins (MM020)

|

2,522

|

4,479

|

4,428

|

4,488

|

5,417

|

929

|

20.7

|

| Decreases: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Transportation equipment:

Aircraft, spacecraft, and related equipment (TE013)

|

8,373

|

9,131

|

9,681

|

10,973

|

9,417

|

-1,557

|

-14.2

|

|

Motor vehicles (TE009)

|

1,526

|

1,856

|

2,144

|

2,247

|

1,899

|

-348

|

-15.5

|

|

Medicinal chemicals (CH019)

|

3,281

|

3,496

|

4,810

|

4,226

|

3,639

|

-587

|

-13.9

|

| All other |

30,528

|

34,205

|

34,719

|

33,032

|

33,644

|

612

|

1.9

|

| Total |

47,361

|

53,913

|

56,095

|

55,289

|

56,329

|

1,040

|

1.9

|

| U.S. general imports: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Increases: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Transportation equipment:

Internal combustion piston engines, other than for aircraft (TE002)

|

1,022

|

1,095

|

963

|

791

|

1,068

|

277

|

35.0

|

|

Aircraft, spacecraft, and related equipment (TE013)

|

1,293

|

1,467

|

1,321

|

1,302

|

1,469

|

167

|

12.8

|

|

Miscellaneous manufactures:

Precious jewelry and related articles (MS006)

|

58

|

50

|

53

|

133

|

365

|

232

|

174.6

|

|

Works of art and miscellaneous manufactured goods (MS017)

|

1,693

|

1,692

|

2,093

|

1,659

|

1,870

|

211

|

12.7

|

| Decreases: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Medicinal chemicals (CH019)

|

4,918

|

5,502

|

10,277

|

7,806

|

5,530

|

-2,275

|

-29.2

|

|

Petroleum products (EP005)

|

6,211

|

5,366

|

3,371

|

2,620

|

2,500

|

-120

|

-4.6

|

|

Precious metals and non-numismatic coins (MM020)

|

1,004

|

944

|

484

|

720

|

623

|

-96

|

-13.4

|

| All other |

36,542

|

38,573

|

39,430

|

39,242

|

39,650

|

408

|

1.0

|

| Total |

52,741

|

54,689

|

57,993

|

54,272

|

53,075

|

-1,197

|

-2.2

|

Source: Compiled from official statistics of the U.S. Department of Commerce.

Note: Import values are based on customs value; export values are based on free along ship value, U.S. port of export. Calculations based on unrounded data.

U.S. general imports of precious jewelry and related articles and of works of art in the miscellaneous manufactures sector also increased from the UK in 2017. Imports in the first category grew by $232 million (up 174.6 percent), while art imports grew by $211 million (up 12.7 percent). Globally, the art market grew in 2017; the United States and the United Kingdom were the second- and third-largest markets, respectively (China was the largest).[17] Precious stones and jewelry are in the UK’s top five global product export groups, with the United States in the top five destination markets.[18] U.S. demand in the gold jewelry market increased 4 percent between the second quarter in 2016 and the second quarter in 2017,[19] while demand in the fourth quarter of 2017 was the highest in nearly a decade.[20]

The decline in prices for generic drugs[21] was the main cause of a decrease in value, but not quantity, of U.S. general imports from the UK in the chemicals and related products sector. U.S. general imports of medicinal chemicals from the UK fell by $2.3 billion from 2016 to 2017. This decline was driven largely by a decline in import value of medicaments)—specifically, medicaments in measured doses (excluding vaccines), imports of which decreased $1.0 billion in value (34.7 percent) during 2016–17. While the value of these imports decreased, import quantities from the UK rose 2,107 metric tons (18.8 percent) from 2016 to 2017.[22] These medicaments in measured doses were the top U.S. import in the chemicals and related products sector, accounting for 20.9 percent of imports from the UK in that sector and 3.9 percent of total imports in 2017.

U.S. Merchandise Trade Balance

The U.S. trade surplus with the UK tripled to $3.3 billion in 2017 (up $2.2 billion, or 220 percent). The most significant shifts occurred in energy-related products, which moved from a deficit to surplus (rising $2 billion); in chemicals and related products, which saw a decrease in the deficit of $1.4 billion; and in minerals and metals, for which the surplus increased by $982 million. The increasing U.S. trade surplus with the UK was partially offset, however, by a $2.1 billion reversal in what had previously been a trade surplus in transportation equipment. The increase in the surplus can be partially attributed to the recovering but still weakened British pound, stemming from the Brexit referendum in 2016.

[1] Hunt and Wheeler, “Brexit: All You Need to Know,” May 24, 2018.

[2] Duncan, “Brexit, Sterling, and Spending Power,” August 3, 2017.

[3] Malaket, “What Does Brexit Mean for Trade?” July 4, 2016.

[4] Giles, “Squeeze on UK Living Standards,” December 27, 2017.

[5] Guardian, “How Has the Brexit Vote Affected the Economy?” February 22, 2018.

[6] EIA, “Today in Energy: U.S. Crude Oil Exports,” March 15, 2018.

[7] EIA, “Today in Energy: Crude Oil Prices Increased in 2017,” January 3, 2018.

[8] IHS Markit, World Trade Atlas database (HS 2709; accessed April 12, 2018).

[9] Bituminous coal, HS 2701.12, includes thermal coal, used for power generation, and metallurgical coal, used mainly for steel production. World Trade Atlas database (HS 2701.12, accessed April 12, 2018).

[10] In 2016, two coal-fired power plants—Longannet in Scotland and Ferrybridge in England—closed, further reducing the need for coal in the UK. Du, “UK Coal Consumption Slumps 29% in 2017,” February 24, 2018.

[11] Du, “UK Coal Consumption Slumps 29% in 2017,” February 24, 2018.

[12] IHS Markit, World Trade Atlas database (HS 2701.12; accessed April 20, 2018).

[13] USITC DataWeb/USDOC (commodity group MM020A; accessed April 24, 2018).

[14] Ash, “Gold Bullion Price Up 12% in 2017,” December 30, 2017.

[15] USITC DataWeb/USDOC (commodity group TE013; accessed April 24, 2018).

[16] USDOC, ITA, Export.gov, “United Kingdom—Aerospace Products,” November 21, 2017.

[18] IHS Markit, World Trade Atlas database (HS 2701.12; accessed April 20, 2018); IHS Markit, Global Trade Atlas (HS 71; accessed May 6, 2018).

[19] DeMarco, “Global Gold Jewelry Demand Improves,” August 3, 2017.

[20] World Gold Council, “Gold Demand Trends Full Year 2017,” February 6, 2018.

[21] MedCity News, “Biotech,” January 5, 2017.

[22] IHS Markit, World Trade Atlas database (HS 3004.90; accessed April 20, 2018). The product category is “Medicaments (excluding goods of heading 3002, 3005, or 3006) consisting of mixed or unmixed products for therapeutic or prophylactic uses, put up in measured doses (including those in the form of transdermal administration systems) or in forms or packings for retail sale: Other.”

Bibliography

Ash, Adrian. “Gold Bullion Price Up 12% in 2017 as Stock Markets Add 20%.” Gold News, December 30, 2017. https://www.bullionvault.com/gold-news/gold-bullion-price-2017-123020171.

DeMarco, Anthony. “Global Gold Jewelry Demand Improves, but Weakness Prevails.” Forbes, August 3, 2017. https://www.forbes.com/sites/anthonydemarco/2017/08/03/global-gold-jewelry-demand-improves-but-weakness-still-prevails/#53e82a3f4bb8.

Du, Becky. “UK Coal Consumption Slumps 29% in 2017.” Shanxi Fenwei Energy, February 24, 2018. https://www.sxcoal.com/news/4568993/info/en.

Duncan, Eleanor. “Brexit, Sterling, and Spending Power.” Financial Times, August 3, 2017. https://www.ftadviser.com/investments/2017/08/03/brexit-sterling-and-spending-power/.

Ehrmann, Thierry. “2017 Summary—The Art Market Enters a New Phase.” In Artprice, The Art Market in 2017. https://www.artprice.com/artprice-reports/the-art-market-in-2017/2017-summary-the-art-market-enters-a-new-phase/ (accessed May 3, 2018).

EIA. See U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA).

Federal Reserve System. “Foreign Exchange Rates: H.10; Country Data.” https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h10/hist/ (accessed May 6, 2018).

Giles, Chris. “Squeeze on UK Living Standards Is the Theme of 2017.” Financial Times, December 27, 2017. https://www.ft.com/content/90c628a4-e715-11e7-97e2-916d4fbac0da.

Guardian. “How Has the Brexit Vote Affected the Economy? February Verdict,” February 22, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2018/feb/22/how-has-the-brexit-vote-affected-the-economy-february-verdict.

Herszenhorn, David M., and Tom McTague. “UK Officials Float Brexit Customs Compromise.” Politico, May 18, 2018. https://www.politico.eu/article/brexit-customs-trade-eu-northern-ireland-uk-officials-float-brexit-customs-compromise/.

Hunt, Alex, and Brian Wheeler. “Brexit: All You Need to Know about the UK Leaving the EU.” BBC News, May 24, 2018. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-politics-32810887.

IHS Markit. World Trade Atlas database (accessed April 12, 2018) (fee required).

Malaket, Alexander. “What Does Brexit Mean for Trade?” World Economic Forum Agenda, July 4, 2016. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/07/trade-finance-and-the-brexit/.

MedCity News. “Biotech: Here’s an Infographic of Drug Patents Expiring in 2017,” January 5, 2017. https://medcitynews.com/2017/01/infographic-drug-patents-expiring-2017/?rf=1.

U.S. Department of Commerce (USDOC). International Trade Administration (ITA). Export.gov. “United Kingdom—Aerospace Products.” United Kingdom Country Commercial Guide, November 21, 2017. https://www.export.gov/article?id=United-Kingdom-Aerospace-Products.

U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). “Today in Energy: Crude Oil Prices Increased in 2017, and Brent-WTI Spread Widened,” January 3, 2018. https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=34372.

U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). “Today in Energy: U.S. Crude Oil Exports Increased and Reached More Destinations in 2017,” March 15, 2018. https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=35352.

World Gold Council. “Gold Demand Trends Full Year 2017: Jewellery,” February 6, 2018. https://www.gold.org/research/gold-demand-trends/gold-demand-trends-full-year-2017/jewellery.