Section 232 and 301 Trade Actions in 2018

Marin Weaver

![]() View PDF Version

View PDF Version

![]() Timeline of Major Trade Policy Actions Regarding Section 232 and Section 301 Tariffs

Timeline of Major Trade Policy Actions Regarding Section 232 and Section 301 Tariffs

To view changing data, hover over or touch the animated graphic below.

To view changing data, hover over or touch the animated graphic below.In 2018, after certain trade actions by the United States and some of its largest trading partners, including China, Canada, Mexico, and the European Union (EU), observable trade shifts occurred for a number of products. The first part of this chapter aims to describe the trade actions taken by the President under section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 (section 232) and sections 301–310 of the Trade Act of 1974 (section 301),[1] and the foreign responses to the U.S. actions under these authorities of the law. The second part presents data on the shifts in 2018 U.S. trade for trading partners and for products covered by those two authorities, as well as by additional duties imposed in response by seven trading partners (China, Canada, Mexico, the EU, Russia, Turkey, and India). This chapter demonstrates that trends in product-level trade flows varied after tariffs were applied. Examples follow of some of the types of trade responses observed in the data for the covered products.

In 2018, for the first time in more than 30 years, a President took action under section 232.[2] This section of the law allows a U.S. President to take action—including imposing tariffs or quotas—if, after an investigation, the U.S. Department of Commerce (Commerce) finds that subject imports “threaten to impair national security.”[3] Between 1964 and 2016, the United States initiated 26 section 232 investigations, the most recent of which was on iron ore and semifinished steel in 2001.[4] Of those, according to a Congressional Research Service (CRS) report, Commerce (or another investigating agency)[5] found that there was a potential national security threat nine times and that a U.S. President took action based on these findings six times.[6]

During 2017–19, the Secretary of Commerce (the Secretary) initiated five section 232 investigations. The first two, covering certain steel articles and aluminum products, were completed and resulted in Presidential action during 2018 (table ST.1).[7] Commerce delivered these reports in January 2018. The Secretary found that “the present quantities and circumstance” of steel and aluminum imports are “weakening our internal economy and threaten to impair the national security as defined in section 232.”[8] The “circumstance” noted for both products was global excess capacity for both aluminum and steel.[9] The Secretary also noted a number of other important factors in support of his recommendation for each product group. These included, for example, “the risk of becoming completely reliant on foreign producers of high-purity aluminum” and “the reduction in basic U.S. oxygen furnace facilities since 2001” for steel production.[10] The President agreed with the Secretary’s findings for both steel and aluminum.[11]

In March 2018, the President imposed duties on U.S. imports of certain steel products (25 percent) and certain aluminum products (10 percent) from all countries except Canada and Mexico.[12] (Throughout this report, these tariffs are referred to as “section 232 tariffs.”) According to the President’s proclamations, the goal of these section 232 tariffs is to adjust the imports of steel articles and of aluminum “so that such imports will not threaten to impair the national security.”[13] In addition, the President’s proclamations stated that the section 232 tariffs would enable the United States to utilize idle or closed steel and aluminum facilities, including mills; preserve workers’ skills; reduce dependence on foreign producers; and ensure a level domestic supply of steel and aluminum “necessary for critical industries and national defense.”[14]

Table ST.1 U.S. section 232 investigations, 2017–19

|

Initiation date |

Brief description of product(s) |

Status |

Initial presidential decision |

|---|---|---|---|

|

April 19, 2017 |

Certain steel products including stainless and carbon and alloy products which are pipe and tube, flat, and long or in semifinished forms |

Complete; Presidential action announced March 8, 2018. |

Concurred with the Secretary’s findings. Imposed a 25% tariff on steel articles.a |

|

April 26, 2017 |

Certain aluminum products, including unwrought aluminum, bars, rods, wire, certain plates and sheets, certain foil, tubes and pipes and their fittings |

Complete; Presidential action announced March 8, 2018. |

Concurred with the Secretary’s findings. Imposed a 10% tariff on aluminum.a |

|

May 23, 2018 |

Certain automobiles and certain automobile parts |

Complete;b Presidential action announced May 17, 2019. |

Concurred with the Secretary’s findings. The President directed the U.S. Trade Representative to “pursue negotiation of agreements . . . to address the threatened impairment of the national security” for these products and to monitor imports.c |

|

July 18, 2018 |

Uranium |

Complete; presidential memorandum issued July 12, 2019. |

Did “not concur with the Secretary’s finding that uranium imports threaten to impair the national security.” No tariffs were imposed. Established the United States Nuclear Fuel Working Group to study topics including U.S. nuclear fuel production and supply chain. The Working Group has not yet released its recommendations. |

|

March 4, 2019 |

Titanium sponge |

Ongoing |

N/A |

Sources: 82 Fed. Reg. 19205 (April 26, 2017); 82 Fed. Reg. 21509 (May 9, 2017); USDOC, BIS, The Effect of Imports of Steel, January 11, 2018, 18, 21–22; USDOC, BIS, The Effect of Imports of Aluminum, January 17, 2018, 18, 20; Proclamation No. 9704, 83 Fed. Reg. 11619 (March 15, 2018); Proclamation 9705, 83 Fed. Reg. 11625 (March 15, 2018); Proclamation 9886, 84 Fed. Reg. 23421 (May 21, 2019); 83 Fed. Reg. 24735 (May 30, 2018); 83 Fed. Reg. 35204 (July 25, 2018); 84 Fed. Reg. 8503 (March 8, 2019); Proclamation 9888, 84 Fed. Reg. 23433 (May 21, 2019); Presidential Memorandum, Memorandum on the Effect of Uranium Imports on the National Security and Establishment of the United States Nuclear Fuel Working Group, July 12, 2019.

Notes: The brief description of products is for illustrative purposes. See Proclamations 9704 and 9705 for the definitive list of products subject to section 232 tariffs for the completed investigations. All tariffs discussed in this chapter are ad valorem duties unless otherwise noted. N/A= not applicable. This table is current as of October 1, 2019.

a Canada and Mexico were initially excluded from these tariffs.

b Commerce’s report was delivered to the President but has not been made public.

c The EU and Japan were specifically flagged for negotiations. No tariffs were imposed.

When announcing the section 232 tariffs, the President stated that trading partners with which the United States has “important security relationships” could discuss alternative ways to address the national security problems caused by steel and aluminum imports.[15] During 2018, the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) led negotiations with seven trading partners that the President determined have important security relationships with the United States: Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, the EU, Mexico, and South Korea.[16]

The President’s grounds for negotiations with all seven trading partners included shared concerns about global excess capacity in the steel and aluminum industries and strong economic integration or partnerships. In his proclamations, the President also noted other specific grounds for each country—for example, certain shared commitments supporting “national security concerns” (e.g., with South Korea, North Korea’s nuclear threat; with Argentina and Brazil, Latin American security concerns).[17] In these initial proclamations, the President also delayed the application of the section 232 tariffs for these seven trading partners—indefinitely in some cases, temporarily in others.[18]

As a result of these negotiations, the following adjustments had been made to the initial section 232 tariffs as of October 2019 (see also the timeline above):

- Argentina: On March 22, 2018, the President temporarily suspended section 232 tariffs.[19] Effective June 1, 2018, annual quotas were established for U.S. imports of Argentinian steel and aluminum products (which, for 2018, took into account all Argentinian steel and aluminum products imported since January 1, 2018).[20]

- Australia: On March 22, 2018, the President temporarily suspended section 232 tariffs.[21] On May 31, 2018, the President announced that, in lieu of tariffs, to address the section 232 concerns “the United States agreed on a range of measures” with Australia. These included measures to reduce excess aluminum and steel production and capacity, “measures that will contribute to increased capacity utilization in the United States, and measures to prevent the transshipment of aluminum articles and avoid import surges.”[22]

- Brazil: On March 22, 2018, the President temporarily suspended section 232 tariffs.[23] Effective June 1, 2018, annual quotas were established for U.S. imports of Brazilian steel products (which, for 2018, took into account all Brazilian steel products imported since January 1, 2018).[24] Also on June 1, 2018, aluminum imports from Brazil became subject to the section 232 tariffs.[25]

- Canada and Mexico: On March 8, 2018, the President temporarily suspended section 232 tariffs. However, he applied them to both steel and aluminum products effective June 1, 2018.[26] The President lifted section 232 tariffs on steel and aluminum from Canada and Mexico on a “long-term basis” starting on May 20, 2019, after the United States “successfully concluded discussions with Canada and Mexico on satisfactory alternative means to address the threatened impairment of the national security posed by” imports of these products from both countries.[27] The agreed-upon means were not specified in public statements.

- European Union: On March 22, 2018, the President temporarily suspended section 232 tariffs. However, negotiations did not lead to permanent suspension, and section 232 tariffs were applied to both steel and aluminum products starting on June 1, 2018.[28]

- South Korea: On March 22, 2018, the President temporarily suspended section 232 tariffs.[29] In April 30, 2018, the President announced that annual quotas were established for steel that would take effect “as soon as practicable” and would take into account all imports from South Korea since January 1, 2018.[30] Starting on May 1, 2018, aluminum imports became subject to the section 232 tariffs.[31]

The President instructed the Secretary to create a process through which certain imported products would be excluded from the section 232 steel and aluminum tariffs.[32] The President authorized the Secretary to grant exclusions if (1) the steel or aluminum article is not produced in the United States “in a sufficient and reasonably available amount”; (2) the steel or aluminum article is not produced in the United States “of a satisfactory quality”; or (3) the steel or aluminum article is needed for “specific national security considerations.”[33] In March 2018, Commerce, through the Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS), created an exclusion process, which includes a period during which all requests for exclusions are made available on a government website to allow for public comment.[34] Only affected parties located in the United States, including buyers of steel and aluminum articles, may request exclusions in this ongoing process.[35]

In June 2018, Commerce began issuing decisions on exclusion requests, granting some while denying others.[36] Estimates vary about how many exclusions have been requested and how many exclusion decisions Commerce has made.[37] According to a CRS report, as of March 4, 2019, Commerce had granted 16,500 steel exclusion requests (out of about 70,000 submitted requests) and 3,000 aluminum exclusion requests (out of about 10,000).[38]

A number of U.S. trading partners argued that the section 232 tariffs are safeguard measures that are not compliant with WTO rules, and a number of trading partners threatened to impose additional duties on U.S. exports.[39] Between April and August 2018, nine trading partners—Canada, China, the EU, India, Mexico, Norway, Russia, Switzerland, and Turkey—filed disputes against the United States at the World Trade Organization (WTO) concerning the U.S. section 232 tariffs.[40] All the complaints alleged that the section 232 tariffs are inconsistent with certain articles of the WTO’s Agreement on Safeguards and with certain articles of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade of 1994 (GATT).[41] On these grounds and others, trading partners contend that WTO rules allow them to apply tariffs on imports from the United States. For example, the EU stated that a “the WTO Agreement on Safeguards provides for the right of any exporting member affected by a safeguard measure to suspend the application of substantially equivalent concessions or other obligations to the trade of the WTO Member applying the safeguard measure.”[42]

Seven trading partners ultimately imposed tariffs in response to the U.S. section 232 tariffs on U.S. products in 2018: Canada, China, the EU, India, Mexico, Russia, and Turkey.[43] (In response, the United States filed WTO disputes against all seven countries claiming that these additional duties are inconsistent with Articles I:1, II:1(a), and II:1(b) of GATT.[44]) In reviewing the tariffs imposed in response to the U.S. section 232 by U.S. trading partners, this section focuses on the four largest U.S. trading partners––China, Canada, Mexico, and the EU. As discussed below and in other chapters, there were a number of observable shifts in exports to these countries after the tariffs were imposed in 2018. Details on the additional duties imposed by these trading partners are presented below in table ST.2.

Table ST.2 Additional duties imposed by select trading partners on U.S. imports in response to the U.S. section 232 tariffs, 2018

|

Trading partner |

Products (no. of 8-digit tariff subheadings) |

Duty rates (%) |

Effective date |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Canada |

231 |

25 (steel products); 10 (all other covered products ) |

July 1, 2018a |

|

China |

128 |

25 (pork products and aluminum scrap); 15 (all other covered products) |

April 2, 2018 |

|

European Union |

154 |

25 (all covered products: Stage 1)b |

June 20, 2018 |

|

Mexico |

208 |

Initially between 5 and 25 (certain steel, aluminum, and agricultural products); certain pork and cheese products faced a temporary duty of 10–15%

|

June 5, 2018 (initial); July 5, 2018 (duties on certain pork and cheese products increased to 20–25%)a |

Sources: Government of China, Ministry of Finance, “Taxation Committee Announcement [2018] No. 13,” April 1, 2018; Government of Canada, “Canada Order SOR/2018-152,” and “Canada Order SOR/2018-153,” both June 28, 2018; Government of Canada, “Canada Order SOR/2019-144,” May 19, 2019; Government of Canada, Department of Finance, “Updated—Countermeasures in Response to Unjustified Tariffs,” May 23, 2019; Government of Mexico, “Decreto por el que se Modifica la Tarifa” (Presidential decree modifying the tariff), June 5, 2018; Government of Mexico, “Decreto que Modifica el Diverso por el que se Modifica la Tarifa” (Presidential decree that removes the modified tariff); EC, “Commission Implementing Regulation (EC) 2018/724,” May 17, 2018.

Note: All duties discussed in this chapter are ad valorem duties unless otherwise noted. Duties were imposed in addition to other duties, including WTO most-favored-nation (MFN) duties.

a These tariffs were removed starting May 20, 2019.

b Stage 2 tariffs, which cover a different list of products, are scheduled to start on March 23, 2021, “or upon the adoption by, or notification to, the WTO Dispute Settlement Body of a ruling that the United States' safeguard measures are inconsistent with the relevant provisions of the WTO Agreement, if that is earlier.”

Starting July 1, 2018, Canada imposed additional duties on products from the United States covered by 231 8-digit subheadings, “representing the value of 2017 Canadian exports affected by the U.S. tariffs” (which Canada estimated at $16.6 billion).[45] Canada imposed additional duties of 25 percent on the 131 8-digit subheadings for U.S. steel products and additional duties of 10 percent on the other 100 8-digit subheadings, which included aluminum, agricultural, and wood products. Effective May 20, 2019, Canada repealed its additional duties on the U.S. steel and aluminum products after reaching an agreement with the United States to remove section 232 tariffs on U.S. imports from Canada.[46]

China imposed additional duties on imports from the United States of products covered by 128 8-digit subheadings starting April 2, 2018.[47] Roughly three-quarters of these U.S. products were agricultural items, including pork products, wine, tree nuts, and fresh fruit. The remaining items were aluminum scrap and a number of steel products. China imposed a 15 percent additional duty on all covered products except for pork products and aluminum scrap, which received a 25 percent additional duty.

The EU applied additional duties to imports from the United States in two stages, the first of which impacted trade in 2018. In stage 1, which was effective June 20, 2018, the EU applied additional duties of 25 percent on U.S. products covered by 154 8-digit subheadings. These included a number of steel and aluminum products and a selection of agricultural products such as sweet corn, whiskies, and certain types of rice and juices. Stage 2 is scheduled to start on March 23, 2021, or on an earlier date depending on the WTO dispute settlement body ruling. [48] Stage 2 covers a different list of products, although certain whiskey subheadings are covered in the lists for both stages.

Mexico applied additional duties on products from the United States covered by 208 8-digit subheadings starting on June 5, 2018.[49] The majority of subheadings were for steel products and were subject to a 15 percent additional tariff, although some were subject to a 25 percent tariff. Mexico also applied tariffs of up to 25 percent on a few U.S. agricultural products, including pork products, whiskey, and cheese. All covered products were subject to these additional duties starting June 5, 2018, although for a few pork and cheese products Mexico further increased tariffs on July 5, 2018.[50] Effective May 20, 2019, Mexico repealed its additional duties on the U.S. steel and aluminum products after reaching an agreement with the United States to remove section 232 tariffs on U.S. imports from Mexico.[51]

In 2018, after an investigation under section 301, the President directed the U.S. government to take certain actions towards China, including imposing tariffs on some imports.[52] Section 301 provides authority for the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) to take certain actions after an investigation finding among other things that “an act, policy, or practice of a foreign country is unreasonable or discriminatory and burdens or restricts U.S. commerce.”[53] Those actions include imposing duties or other import restrictions on goods of the foreign country that is the subject of the finding.[54]

On August 14, 2017, the President directed the U.S. Trade Representative to determine whether to investigate “any of China’s laws, policies, practices, or actions that may be unreasonable or discriminatory and that may be harming American intellectual property rights, innovation, or technology development” under section 301(b) of the Trade Act of 1974.[55] On March 22, 2018, USTR delivered its report outlining the basis for its findings that “the acts, policies, and practices of the Government of China related to technology transfer, intellectual property, and innovation covered in the investigations are unreasonable or discriminatory and burden or restrict U.S. commerce.”[56] That day, based on the findings in USTR’s report, the President directed that the following three actions be taken:[57]

- The U.S. Trade Representative should consider whether to apply additional tariffs to Chinese products (referred to as “section 301 tariffs” in this report),

- The U.S. Trade Representative should “pursue dispute settlement in the WTO to address China’s discriminatory licensing practices,” and

- The Secretary of the Treasury should look into imposing investment restrictions.

This chapter focuses on the first of these actions because it was an important event in terms of the shifts in U.S.-China trade in 2018. The United States has imposed section 301 tariffs on imports from China in tranches (sometimes called lists).[58] During 2018, the United States imposed tariffs in three tranches, which have a combined estimated annual trade value of $250 billion (table ST.3). For context, total U.S. imports from China were valued at $544 billion in 2018.[59] In May 2019, tariffs on tranche 3 were raised from 10 percent to 25 percent,[60] and a fourth tranche was proposed by USTR.[61] On September 1, 2019, the United States began applying tariffs to products in group one of tranche 4.[62]

For each tranche, USTR publicly proposed a “determination of action pursuant to Section 301” and sought public comments on a proposed list of 8-digit subheadings of the Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (HTS) on which to apply tariffs, including through a public hearing.[63] After the public comment period, USTR issued a notice of action with the final list of products and duty rate(s) for a given tranche. The section 301 tariffs are applied “in addition to all other applicable duties, fees, exactions, and charges.”[64] As with the section 232 tariffs, the Administration has provided opportunities for U.S. stakeholders to request product exclusions from the section 301 product lists through a process administered by USTR.[65] USTR issued the first of a group of exclusions in late December 2018.[66] Hence any exclusions issued in 2018 would have had only a minimal impact on trade in 2018, which is the subject of further discussion below.

The section 301 tariffs imposed in 2018 encompassed a wide range of products—over half of the approximately 11,100 HTS 8-digit subheadings in the U.S. tariff schedule.[67] The first tranche primarily covered advanced technology and machinery products.[68] The second tranche primarily covered plastics and plastic articles and additional advanced technology and machinery products.[69] The third (and largest) tranche covered the widest array of items, including numerous agricultural, mineral, chemical, textile, wood, glass, metal, and furniture products, as well as additional advanced technology and machinery products.[70]

Table ST.3 U.S. Section 301 tariff tranches

|

Tranche |

Products (no. of HTS 8-digit subheadings)a |

USTR estimated value of annual trade (billion $) |

Duty rate (%) |

Effective date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

818 |

34 |

25 |

July 6, 2018 |

|

2 |

284 |

16 |

25 |

August 23, 2018 |

|

3 |

5,733b |

200 |

Initially 10; then 25 |

September 24, 2018 (Initial); May 10, 2019 (increase to 25%)c |

|

4 |

3,805d |

300 |

15 |

September 1, 2019 (Group 1); December 15, 2019 (Group 2) |

Sources: 83 Fed. Reg. 28710 (June 20, 2018); 83 Fed. Reg. 40823 (August 16, 2018); 83 Fed. Reg. 47974 (September 21, 2018); 83 Fed. Reg. 49753 (September 28, 2018); 84 Fed. Reg. 20496 (May 9, 2019); 84 Fed. Reg. 26930 (June 10, 2019); 84 Fed. Reg. 22564 (May 17, 2019); 84 Fed. Reg. 43304 (August 20, 2019); 84 Fed. Reg. 45821 (August 30, 2019).

Notes: The number of products listed for each tranche is based on official notices and does not reflect any exclusions granted. All tariffs discussed in this chapter are ad valorem duties unless otherwise noted. The information in the table is current as of October 1, 2019.

a While most products are listed at the HTS 8-digit subheading level, tranches 3 and 4 include “full and partial tariff subheadings.” Product counts used reflect counts published by USTR in its final action unless otherwise noted.

b Tranche 3 was modified on September 28, 2018. The initial list covered 5,745 products.

c Tariffs on products covered in tranche 3 were scheduled to rise on January 1, 2019; USTR delayed the imposition of these duties until May 10, 2019, with an exception that goods on the water as of May 10 had until June 15, 2019, to enter the United States at the 10 percent duty rate.

d The tranche 4 count is based on the initial USTR proposal from May 2019. The list was subsequently modified, but USTR’s Federal Register notices on final actions published in August 2019 did not provide a final product count.

China claimed that the section 301 tariffs violate WTO rules and responded by applying additional duties on imports of certain U.S. products.[71] In 2018, it filed two disputes against the United States at the WTO with respect to the U.S. section 301 tariffs, claiming that the “measures appear to be inconsistent with: Articles I:1, II:1(a) and II:1(b) of GATT and Article 23 of the Dispute Settlement Understanding” of the WTO .[72] China issued its additional duties imposed in response to U.S. section 301 tariffs in tranches timed to align with the U.S. section 301 tariffs (table ST.4).[73] Three tranches of additional tariffs were imposed in 2018, and a fourth was imposed on September 1, 2019.[74] China also established an exclusion request process, but it was not in effect until mid-2019.[75]

By October 2018, China’s additional duties imposed in response to the U.S. section 301 tariffs covered 6,085 products with an estimated value of $110 billion.[76] Based on this estimate, these tariffs cover more than two-thirds of Chinese imports from the United States that totaled $154 billion in 2018.[77] As with the U.S. section 301 tariffs, China imposed these duties in addition to any other tariffs. The first tranche included agricultural, aquatic, and automobile items.[78] Soybeans, the largest U.S. agricultural export to China for more than a decade before 2018, were included in tranche 1.[79] The second tranche included vehicles and vehicle parts, a wide range of waste products including plastic and metal, petroleum and oil products, and chemicals. As with the U.S. section 301 tariffs, China’s first two tranches were subject to 25 percent additional duties. The third tranche is by far the largest, covering over 5,000 8-digit subheadings and a wide range of products. China divided tranche 3 products into 4 groups or lists; the first two lists were subject to 10 percent tariffs and the second two lists to 5 percent tariffs, until June 1, 2019, when tariffs for three of the lists rose.[80] In addition, China temporarily suspended tariffs on 211 8-digit subheadings covering autos and automobile parts beginning January 1, 2019.[81]

Table ST.4 China: Tranches of additional duties in response to U.S. Section 301 tariffs

|

Tranche |

Products (no. of 8-digit subheadings) |

Estimated value of annual trade (billion $)a |

Duty rate (%) |

Effective date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

545 |

34 |

25 |

July 6, 2018 |

|

2 |

333 |

16 |

25 |

August 23, 2018 |

|

3 |

5,207b |

60 |

Initial rates of 5 or 10; rising to 10, 20 or 25 for some productsc |

September 24, 2018 (initial); June 1, 2019 (increased to 10, 20 or 25 percent)c |

|

4 |

5,078c |

75 |

5 or 10 (groups 1 and 2). |

September 1, 2019 (group 1); December 15, 2019 (group 2) |

Sources: Government of China, Ministry of Finance, “Taxation Committee Announcement [2018] No. 5,” June 16, 2018; Government of China, Ministry of Commerce, Announcement [2018] No. 64,” August 8, 2018; Government of China, Ministry of Commerce, “Announcement [2018] No. 69,” September 18, 2018; Sandler Travis, China 301 List 1; Sandler Travis, China 301 List 2 Version 2; Sandler Travis, China 301 Lists 3.1–3.4 (all accessed July 9, 2019); Government of China, Ministry of Finance, “The State Council Customs Tariff Commission Issued a Notice,” May 13, 2019; Government of China, Ministry of Finance, “Taxation Committee Announcement [2019] No. 4,” August 23, 2019; USDOC, ITA, Current Foreign Retaliatory Actions (accessed July 9, 2019); Curran, Mayeda, and Leonard, “China Strikes $60 Billion of U.S. Goods,” September 17, 2018; USITC DataWeb/USDOC (accessed July 31, 2019).

Note: All tariffs discussed in this chapter are ad valorem duties unless otherwise noted. Product counts are from announcements made by the government of China and do not reflect any exclusions granted. Some products were included in more than one tranche. The information in the table is current as of October 1, 2019.

a The Government of China through the Ministry of Finance and/or Ministry of Commerce provided estimated values for each of its tariff tranches. China appears to be attempting to mirror the United States, estimating its tranche 1 at $34 billion, its tranche 2 at $16 billion, and its tranche 3 at $200 billion. However, the tranche 3 estimate exceeds total U.S. exports to China. Bloomberg news reporters estimated tranche 3 at $60 billion, which, combined with the estimated combined values of tranches 1 and 2 ($50 billion) is close or equal to total U.S. exports to China (which were $120 billion in 2017 and $110 billion in 2018). The table therefore uses the Bloomberg estimate for tranche 3.

b China divided tranche 3 products into four groups or lists. List 3.1 has 2,493 products, list 3.2 has 1,078, list 3.3 has 974, and list 3.4 has 662.

c Products on lists 3.1 and 3.2 were subject to 10 percent tariffs, while products on the other two lists were subject to 5 percent tariffs until June 1, 2019. Tariffs rose to 25 percent of list 3.1, to 20 percent for list 3.2, and to 10 percent of list 3.3 on June 1, 2019. Tariffs for list 3.4 did not change on June 1, 2019.

d China’s tranche 4 has two stages, each of which has 4 product groupings.

When comparing 2017 and 2018 trade data there are a number of observable U.S. shifts in merchandise trade whose timing corresponds with actions related to the section 232 and section 301 tariffs imposed by the United States and to the additional duties imposed in response by seven trading partners. (These duties imposed by the United States and its trading partners are collectively referred to below as “section 232 and section 301 tariff actions”). This section first presents the shifts in trade of products impacted by section 232 and section 301 tariff actions at the country level. It then provides examples of distinct types of observable trends at the product level. For these examples, information is presented from third-party sources, including industry and government, attributing the shifts to the section 232 and section 301 tariff actions. However, the Commission has not independently analyzed if there are causal linkages.

U.S. exports to the seven trading partners that imposed additional duties in response to the U.S. section 232 and section 301 tariffs noticeably shifted in 2018.[82] In 2017–18, U.S. exports of products covered by these tariffs (covered products) declined with respect to five out of seven of these partners when comparing the two full years (table ST.5). However, most of these additional duties took effect between May and July of 2018.[83] As table ST.5 shows, in quarters 3 and 4, U.S. exports of covered products declined to all seven trading partners. U.S. exports of items that were not covered by the additional duties (non-covered products) did not show the same trends for most of the seven trading partners. U.S. exports of non-covered products rose to all of the trading partners that imposed additional duties, with the exception of Russia, between 2017 and 2018, both annually and when only the second half of each year is examined.

Table ST.5 Changes in U.S. exports between 2017 and 2018, by trading partner

|

Trading partner |

Products covered by additional duties imposed in response to U.S. section 232 and 301 tariffs |

Products not covered by additional duties imposed in response to U.S. section 232 and 301 tariffs |

||||||

|

Annual absolute change (million $) |

% change |

Q3 + Q4 absolute change (million $) |

% change |

Annual absolute change (million $) |

% change |

Q3 + Q4 absolute change (million $) |

% change |

|

|

Canada |

-971.3 |

-6 |

-1,165.9 |

-15 |

14,809.4 |

7 |

4,004.9 |

4 |

|

China |

-14,975.7 |

-17 |

-15,627.1 |

-34 |

4,639.3 |

14 |

512.9 |

3 |

|

EU |

246.4 |

4 |

-304.4 |

-10 |

32,090.5 |

14 |

14,341.7 |

12 |

|

India |

18.4 |

1 |

-69.3 |

-9 |

7,061.6 |

38 |

3,461.1 |

34 |

|

Mexico |

-68.6 |

-2 |

-212.4 |

-10 |

16,921.3 |

9 |

8,411.6 |

9 |

|

Russia |

-17.4 |

-7 |

-93.4 |

-53 |

-158.7 |

-3 |

-374.5 |

-11 |

|

Turkey |

-69.3 |

-4 |

-202.6 |

-24 |

636.0 |

8 |

344.1 |

9 |

Source: USITC DataWeb/USDOC (accessed June 11, 2019).

Note: This table shows data for the seven trading partners that imposed additional duties on U.S. exports in response to U.S. section 232 and 301 tariffs. Q = quarter. Quarters 3 and 4 cover July through December. Product coverage and tariff rates varied by trading partner. EU = European Union; this term includes the 28 countries that were member states in 2017 and 2018.

U.S. imports of covered products generally showed continued growth after the application of section 232 and section 301 tariffs for the highlighted countries (table ST.6). Table ST.6 shows the seven trading partners with which the United States negotiated on the section 232 tariffs (collectively referred to as the “negotiating trading partners”) and China, which is subject to both section 232 and section 301 tariffs. Broadly speaking, U.S. imports of non-covered products grew at a consistent rate, comparing annual growth between 2017 and 2018 to growth in the second half of each year (quarters 3 and 4).

Table ST.6 Changes in U.S. imports between 2017 and 2018, by trading partner

|

Trading partner |

Products covered by section 232 and section 301 tariffs |

Products not covered by section 232 and section 301 tariffs |

||||||

|

Annual absolute change (million $) |

% change |

Q3 + Q4 absolute change (million $) |

% change |

Annual absolute change (million $) |

% change |

Q3 + Q4 absolute change (million $) |

% change |

|

|

China |

21,260 |

10 |

8,309 |

8 |

17,727 |

6 |

10,228 |

6 |

|

Canada |

378 |

3 |

-501 |

-8 |

19,944 |

7 |

10,388 |

7 |

|

EU |

931 |

12 |

282 |

7 |

55,037 |

13 |

25,816 |

12 |

|

Mexico |

544 |

18 |

230 |

15 |

33,420 |

11 |

18,678 |

12 |

|

Brazil |

94 |

4 |

135 |

10 |

1,815 |

7 |

1,033 |

7 |

|

South Korea |

-308 |

-11 |

-499 |

-32 |

4,180 |

6 |

3,938 |

11 |

|

Argentina |

-106 |

-14 |

-151 |

-31 |

84 |

2 |

59 |

3 |

|

Australia |

154 |

37 |

166 |

73 |

-260 |

-3 |

48 |

1 |

|

Rest of world |

-66 |

0 |

-219 |

-3 |

68,466 |

10 |

36,833 |

11 |

|

World total |

22,880 |

9 |

7,752 |

6 |

200,414 |

10 |

107,020 |

10 |

Source: USITC DataWeb/USDOC (accessed June 27, and July 1, 2019).

Note: The table shows data for China and the seven trading partners that held section 232 national security negotiations with the United States. Countries are listed by value of total U.S. imports. Q = quarter. Quarters 3 and 4 cover July through December. EU = European Union; this term includes the 28 countries that were member states in 2017 and 2018.

Without considering U.S. imports from China (discussed separately below), which in 2018 were subject to both U.S. 232 and 301 tariffs, in 2017–18 U.S. imports covered by additional tariffs were almost entirely of steel and aluminum products covered by the section 232 actions. Imports from the “rest of the world,” which became subject to the section 232 tariffs on March 23, 2018, fell slightly on an annual basis. This was driven by the decline in the second half of the year (table ST.6). Conversely, U.S. imports of products covered by section 232 tariffs from five of the seven negotiating trading partners (Australia, Brazil, Canada, EU, and Mexico) rose, by value, on an annual basis. However, since the negotiating trading partners did not become subject to section 232 tariffs or negotiated quotas until sometime between May 1 and June 1, 2018, the data for quarters 3 and 4 are most relevant to this discussion.[84]

Covered imports from four of these trading partners (Australia, Brazil, the EU, and Mexico) continued to show year-on-year growth in the second half of 2018, albeit those from two of these partners (the EU and Mexico) grew at slower rates than were seen for the year as a whole. Covered imports from Australia––the only country not ultimately subject to the section 232 tariffs––and Brazil accelerated in the second half of 2018.[85] Covered imports from two other countries––South Korea and Argentina[86]––fell between 2017 and 2018, both annually and at an accelerated rate in the second half of the year; imports from Canada also fell in the second half of the year. The rise in values of steel and aluminum imports from some trading partners during this period is counterintuitive in light of the increased tariffs. However, the total quantity of imported covered steel and aluminum products fell, as shown in example 1 below.

Turning to China, the data show that, despite the section 232 and 301 tariffs, U.S. imports of covered products rose about 10 percent by value between 2017 and 2018.[87] However, the data also show that growth slowed––to 8 percent by value––in the second half of 2018 (quarters 3 and 4), which is when the 301 tariffs were imposed.[88] Due to the wide range of products—and of the units by which they are measured—it is challenging to assess what was driving this trend.[89] (To learn more about the industry commodity sectors that were driving this growth, see the China table in the Trading Partners section and the sector chapters of the report.)

While aggregate trade data imply that the section 232 and section 301 tariff actions contributed to declines in bilateral trade with some countries, shifts in trade data at the product level show a variety of trends. A number of U.S. import and export flows for many covered subheadings show notable declines in 2018 that can be attributed to the tariffs, or the threat of tariffs, according to industry and government sources. However, other products did not follow this trend, which may appear counterintuitive. This is likely because in addition to tariffs, other factors impacted trade trends and influenced which parties absorbed the cost of the tariffs for many products. These include the substitutability of the covered products with other products, the ability to divert trade, and company-specific factors and decisions.

Examining the trade data at the product level revealed several types of trade shifts in 2018 related to section 232 and section 301 actions (e.g., announcements, proposed lists, and actual imposition of tariffs) taking place. The five examples presented below illustrate a few of these shifts, with each highlighting one aspect of the bilateral trade response. These cover a variety of patterns, including: declines after either the imposition of the section 232 or 301 tariffs or the threat of tariffs; temporary increases in shipments in advance of tariffs; and either minimally changed or increased trade after the imposition of these tariffs. These examples are not intended to provide a full picture of the trade shift seen in the data for a given product: additional factors related to trade in several of these products can be found in the sector chapters of this report. Table ST.7 presents a summary of the examples included in this section by type of trade flow.

Table ST.7 Summary of examples presented in this section by type of trade flow

|

Example |

U.S. Exports |

U.S. Imports |

|---|---|---|

|

1. Notable declines in trade after the imposition of tariffs |

Soybeans Certain steel coils |

Steel Aluminum |

|

2. Temporary decrease in U.S. exports after a threat of tariffs |

Crude petroleum |

|

|

3. Temporary increase in trade in advance of tariffs |

Unwrought aluminum |

|

|

4. No notable shift in trade volume after the imposition of tariff because of price adjustments |

Whiskies |

|

|

5. Growth in trade after the imposition of tariff |

Hard cheese |

Brake rotors |

Trade data for some covered products showed a clear, steep drop in the third and fourth quarters of 2018––after the section 232, section 301 tariffs, and additional foreign duties in response to these tariffs were put in place––as compared to the year before. As noted above, by imposing tariffs under section 232, the President sought to reduce U.S. steel and aluminum imports and bolster the domestic steel and aluminum industries for national security reasons. Trade data for 2018 indicate that these tariffs had their intended effect of reducing the volume of imports. From 2017 to 2018, U.S. imports of covered steel and aluminum products fell roughly 12 percent and 10 percent (by volume), respectively.[90] However, because prices rose for both groups of products, imports of aluminum rose 5 percent on a value basis, while imports of steel were flat (increasing less than one-half of 1 percent). (See the Minerals and Metals chapter for more details.)

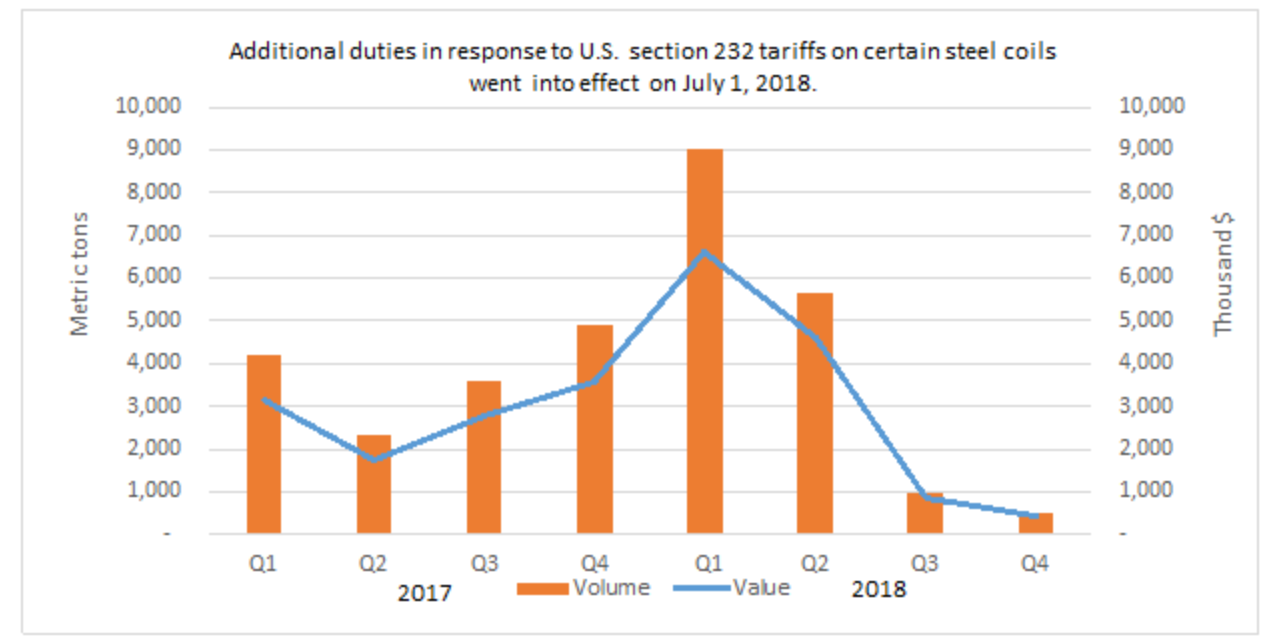

U.S. exports also showed similar shifts—for example, U.S. exports of certain steel coils classified under the international Harmonized Schedule (HS) subheading 7213.91.[91] As noted above, Canada began applying a 25 percent additional duty to these products from the United States on July 1, 2018. As figure ST.1 shows, U.S. exports of certain steel coils to Canada fell sharply following the imposition of tariffs, dropping 80 percent by value and 83 percent by volume in the second half of 2018 (quarters 3 and 4) from the same period in 2017. Before the application of the tariffs, these exports had been increasing and were 127 percent higher, by value, and 123 percent higher, by volume, in the first half of 2018 than in 2017.[92] (More information on other U.S. metal trade shifts can be found in the Minerals and Metals chapter of this report.)

Figure ST.1 Certain steel coils subject to additional duties imposed in response to U.S. section 232 tariffs: U.S. domestic exports to Canada, by quarter, 2017–18

Source: USITC DataWeb/USDOC (accessed June 11, 2019).

Notes: Q = quarter (e.g., quarter 1 is January, February, and March). Based on U.S. domestic exports of products covered by additional duties in response to U.S. section 232 tariffs classified under HTS subheading 7213.91.00.

Notable declines in trade after the imposition of tariffs were not confined to steel and aluminum products. For example, U.S. soybeans—the largest U.S. agricultural export to China—were subject to an additional 25 percent duty in response to the U.S. section 301 tariffs. Between 2017 and 2018, U.S. exports of soybeans to China fell 74 percent by both volume and value.[93] A number of observers, both in the industry and at the U.S. Department of Agriculture, attributed these declines largely to the additional duties and to the related reluctance of Chinese importers to buy U.S. soybeans.[94] (More information on U.S. exports of soybeans can be found in the Agricultural Products chapter of this report.)

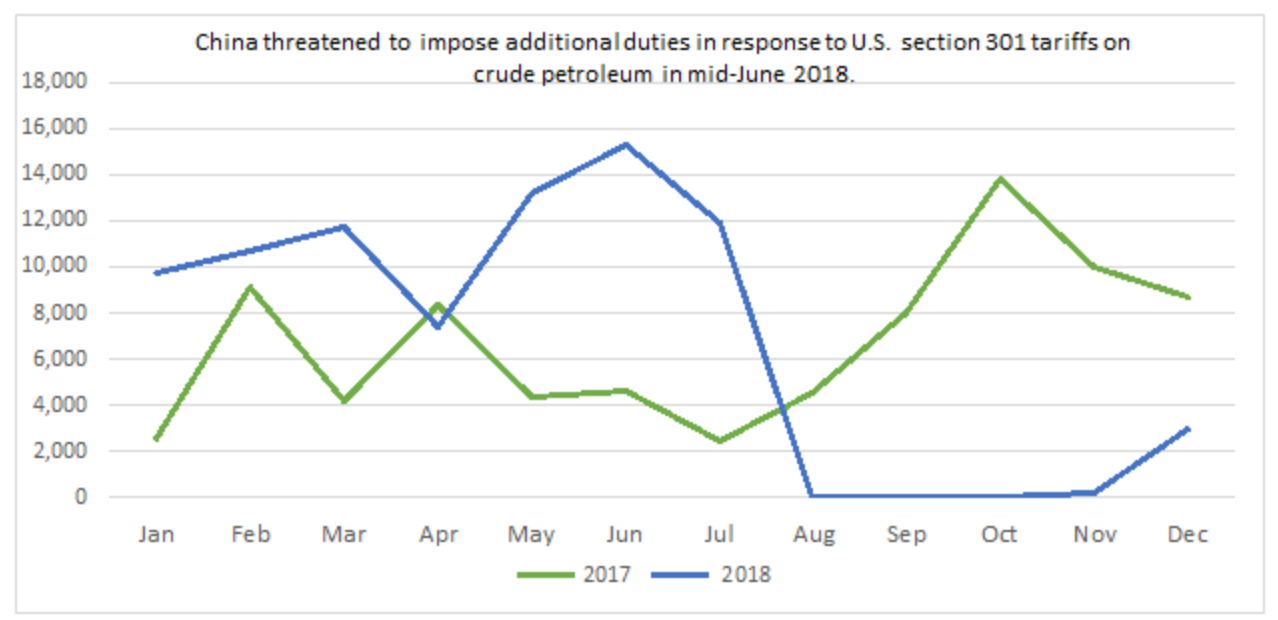

U.S. crude petroleum exports to China show a notable decrease in trade that took place around the time an explicit threat of additional duties was made, regardless of whether they were subsequently imposed. In response to U.S. section 301 tariffs, China threatened to impose additional duties on crude petroleum in mid-June 2018.[95] Starting in August, U.S. exports—which take about 6–8 weeks to reach China––ended as Chinese buyers stopped purchasing crude petroleum from the United States (figure ST.2).[96] Ultimately, China did not include crude petroleum in any of its three 2018 tranches of additional duties imposed in response to the U.S. section 301 tariffs, the last of which was released in September 2018.[97] Chinese buyers resumed purchasing U.S. crude petroleum, and U.S. exports began entering China again in November 2018, albeit at a much lower volume than earlier in the year or during the same period of the previous year.[98] (More information on U.S. crude oil exports to China and other countries can be found in the Energy-related Products chapter.)

Figure ST.2 U.S. exports of crude petroleum to China 2017–18 (thousand barrels)

Source: EIA, Exports by Destination (accessed July 17, 2019).

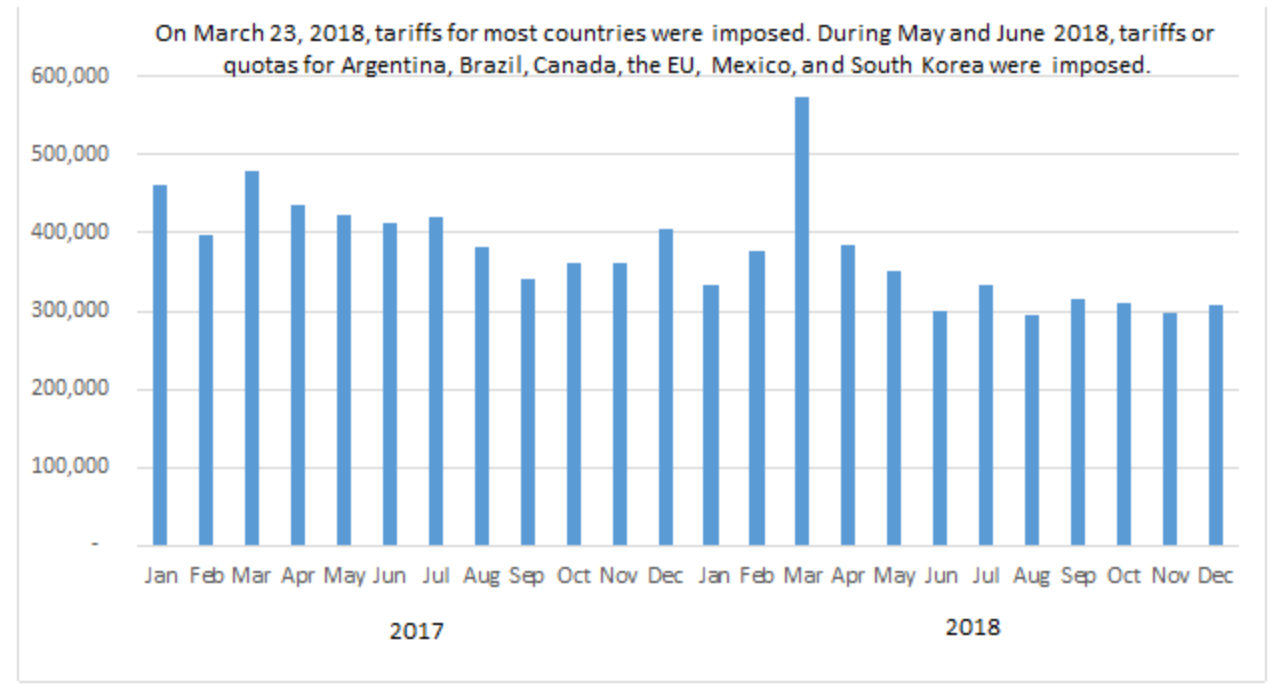

Another observed shift was an increase in trade after the announcement of the additional section 232 or section 301 duties, but before they were applied. Generally, there was advance notice of the products that might become subject to sections 232 and 301 tariffs and the additional duties imposed in response to these by U.S. trading partners. This allowed some importers and exporters time to react and accelerate shipments, building up inventories in advance of the application of the duties (even though, as discussed above, in some cases the tariffs did not materialize during 2018).[99] For example, after section 232 tariffs were announced for most countries on March 8, 2018, U.S. imports of unwrought aluminum, one of the covered products, jumped in March 2018 to the highest level of the two-year period (figure ST.3). Moreover, the U.S. Geological Survey reported an increase in U.S. inventories of unwrought aluminum (also known as primary aluminum) in April and May of 2018.[100] An industry observer credits increases in inventories to aluminum traders stockpiling in the United States in anticipation of the imposition of the section 232 tariffs.[101]

Figure ST.3 U.S. imports of unwrought aluminum, 2017 and 2018, (metric tons)

Source: USITC, DataWeb (accessed July 30, 2019).

Notes: Based on imports for consumption of HTS 7601 from all countries.

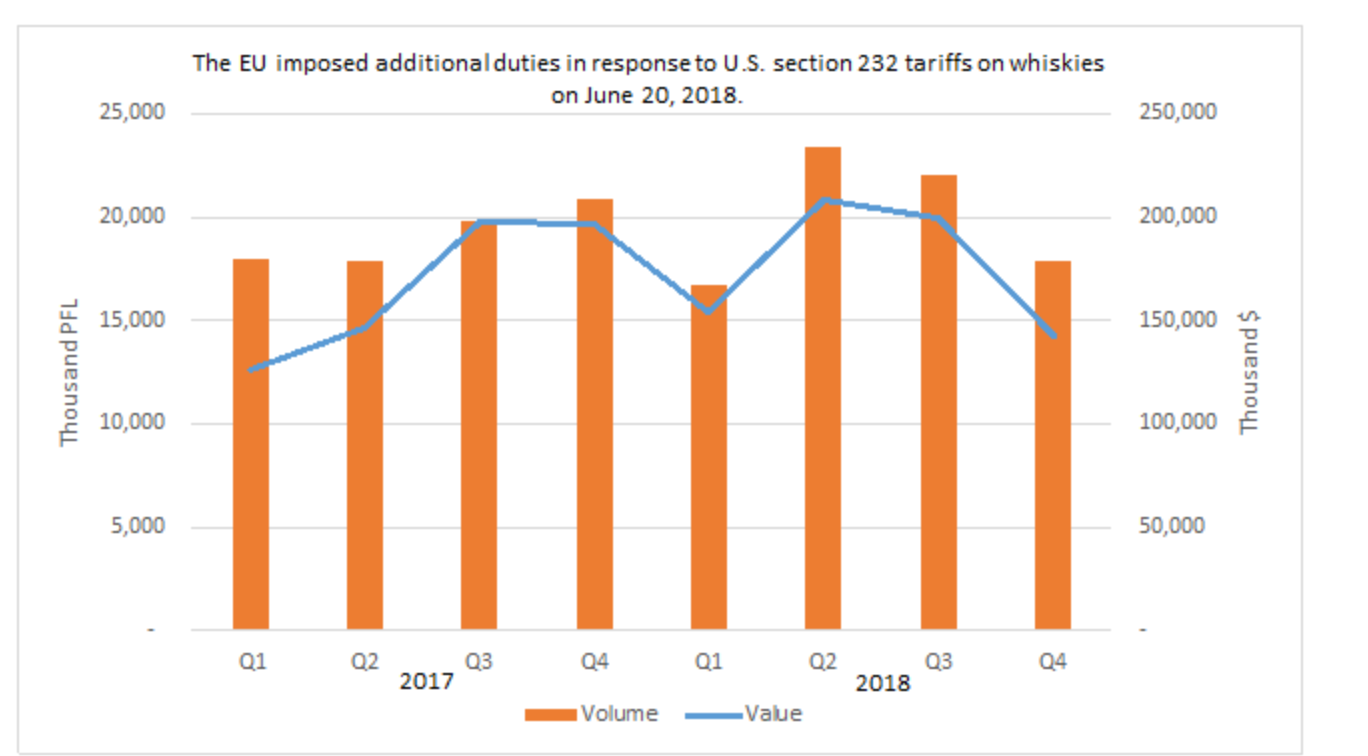

Trade data indicates that on an annual basis U.S. whiskey exports to the EU showed no notable shift in 2017–18, despite whiskey being covered by additional duties in the EU. In June 2018, the EU placed additional duties of 25 percent on nearly all U.S. exports of whiskey in response to the U.S. section 232 tariffs.[102] The EU is the largest market for U.S. whiskey, accounting for 59 percent ($704 million) of U.S. exports in 2018.[103] The EU is also a major producer of whiskey—especially in Scotland, the world’s largest producer.[104]

On an annual basis, U.S. whiskey exports to the EU grew 6 percent by value and 5 percent by volume between 2017 and 2018 (figure ST.4). However, a comparison of partial-year exports (July–December for 2017 and 2018) shows that the value of U.S. exports fell about 13 percent after the duties were in place. This decrease reflects lower prices in the period, as measured by average unit value (AUV). AUV dropped 12 percent in the second half of 2018, while U.S. export quantities fell less sharply at only 2 percent. This indicates that at least some level of tariff absorption by U.S. exporters was occurring. Statements by one of the largest U.S. whiskey producers and exporters, Brown-Forman, support this conclusion.[105] Brown-Forman announced that it had lowered prices in 2018 in response to the additional duties imposed by the EU.[106] Europe continued to be Brown-Forman’s largest export market, accounting for 27 percent of global net sales in 2017 and 26 percent in 2018.[107]

Figure ST.4 Whiskies subject to additional duties imposed in response to U.S. section 232 tariffs: U.S. domestic exports to the EU, 2017–18

Source: USITC DataWeb/USDOC (accessed June 11, 2019)

Note: PFL = proof fluid liter. Q = quarter (e.g., quarter 1 is January, February, and March). Based on U.S. domestic exports to the EU of products covered by additional duties in response to U.S. section 232 tariffs covered under subheadings 2208.30.11, 2208.30.19, 2208.30.82, and 2208.30.88 of the EU tariff code.

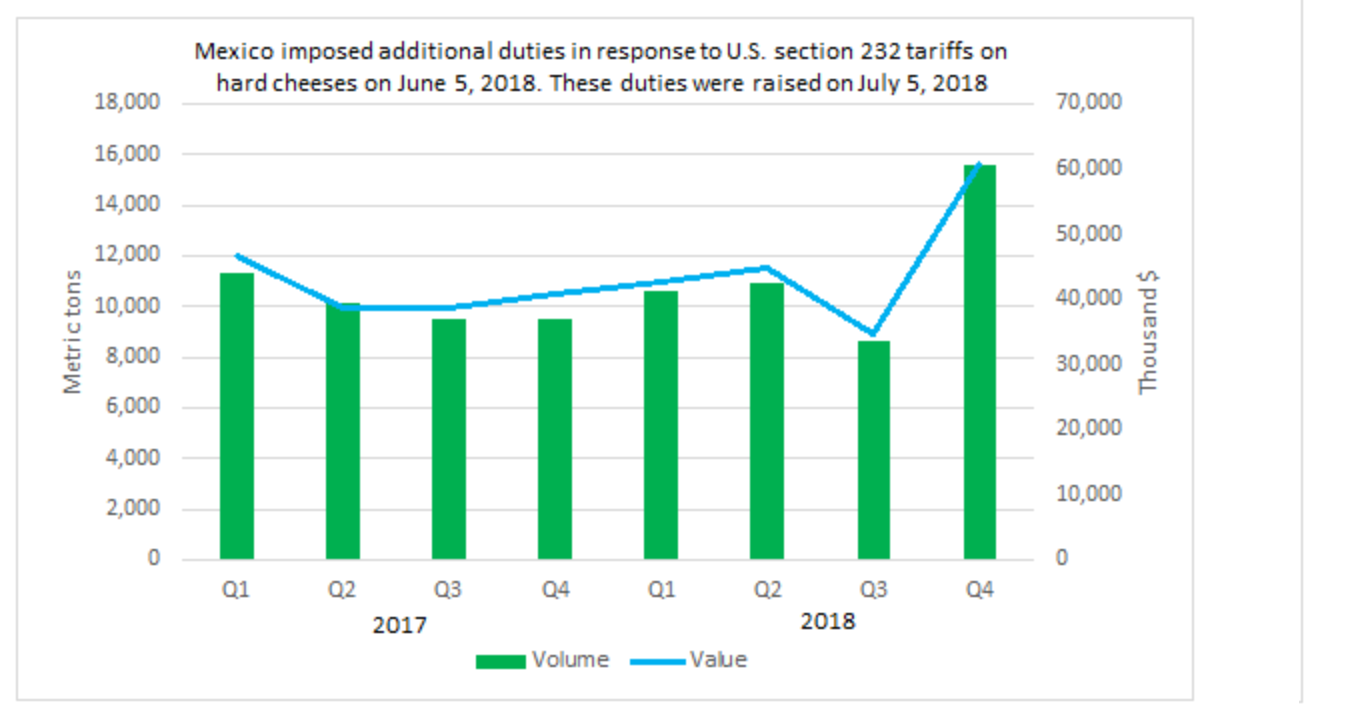

Perhaps counterintuitively, there was observable growth in trade of some products even after the imposition of section 232 or section 301 tariff actions. For example, in response to the U.S. section 232 tariffs, Mexico placed additional duties on nearly all U.S. exports of cheese to Mexico,[108] including cheese covered under HS subheading 0406.90 (“hard cheese”).[109] After July 5, 2018, most U.S. hard cheese exports to Mexico were subject to a 25 percent tariff, and most of the remaining hard cheese exports were subject to a 20 percent tariff. [110] Even so, U.S. exports of covered hard cheese to Mexico grew between 2017 and 2018. Growth occurred not only on an annual basis (rising 11 percent by value and 13 percent by volume) but in the months after tariffs were imposed (figure TS.5). A comparison of exports between July and December (quarters 3 and 4) of 2017 and 2018 shows higher exports in that period: 20 percent by value and 27 percent by volume.[111]

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, a number of factors helped U.S. cheese remain competitive in the Mexican market, even with the imposition of the additional duties in response to the U.S. section 232 tariffs (although other factors may have contributed to the strong growth in fourth quarter 2019). These factors included (1) high demand for imported cheese, especially from United States, which is Mexico’s largest supplier;[112] (2) the price competitiveness of U.S. cheese during this period;[113] and (3) the United States’ geographical advantage compared to other suppliers.[114] Furthermore, the additional duties on U.S. product did not completely eliminate the United States’ tariff advantage over Mexico’s other top suppliers of cheese.[115]

Figure ST.5 Hard cheese subject to additional duties imposed in response to U.S. section 232 tariffs: U.S. domestic exports to Mexico, 2017–18

Source: USITC DataWeb/USDOC (accessed June 11, 2019).

Notes: Q = quarter (e.g., quarter 1 is January, February, and March). Based on U.S. domestic exports of products under HTS subheading 0406.90 subject to additional duties in response to U.S. section 232 tariffs.

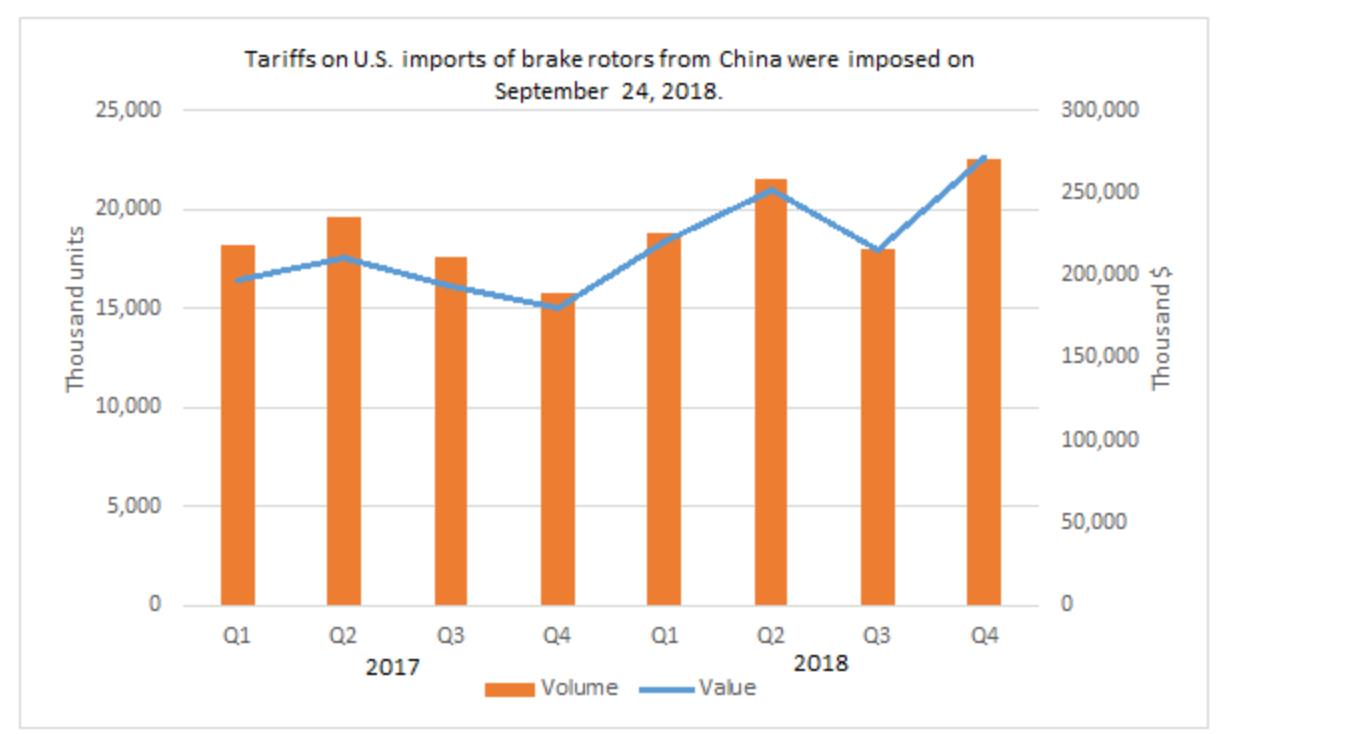

This trend was also observed in certain U.S. imports of covered products, including brake rotors from China, which rose after becoming subject to section 301 tariffs.[116] In July 2018, the United States announced a list of products (for tranche 3) on which it was proposing to impose 10 percent tariffs, including brake rotors (covered under HTS statistical reporting number 8708.30.50.30).[117] These tariffs came into force on brake rotors and other products on September 24, 2018.[118] Despite the tariffs, U.S. imports of brake rotors from China increased from $781 million in 2017 to nearly $960 million in 2018 (figure TS.6). Moreover, imports in the fourth quarter of 2018 totaled over $271 million, higher than in any of the previous seven quarters. According to one industry source, factors unrelated to tariffs likely drove this growth, including the fact that China is the main brake rotor supplier to the United States and that there is too little capacity in the United States to meet domestic demand.[119] An industry analyst stated that the depreciation of the yuan against the dollar and a decision by Chinese suppliers to absorb some tariff-related costs may have also contributed to increased imports.[120]

Figure ST.6 U.S. imports of brake rotors from China, 2017–18

Source: USITC DataWeb/USDOC (accessed September 10, 2019).

Notes: Based on U.S. imports for consumption of HTS statistical reporting number 8708.30.50.30 (brake rotors). Q = quarter (e.g., quarter 1 is January, February, and March).

[1] Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, as amended (19 U.S.C. § 1862); Sections 301–310 of the Trade Act of 1974, as amended (19 U.S.C. §§ 2411–2420).

[2] Proclamation 9704, 83 Fed. Reg. 11619, and Proclamation 9705, 83 Fed. Reg. 11625 (both March 8, 2018); CRS, “Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962,” updated May 23, 2019.

[3] U.S. Presidents are not required to take action even if Commerce finds that subject imports threaten to impair national security. CRS, “Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962,” updated May 23, 2019.

[4] Section 232 investigations may be initiated based on a petition from industry or self-initiated by Commerce. CRS, “Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962,” updated May 23 2019; CRS, Section 232 Investigations, April 2, 2019, 38–39; USDOC, BIS, Section 232 Investigations (accessed June 19, 2019).

[5] Commerce began conducting section 232 investigations in 1980. Between 1973 and 1980, the U.S. Department of the Treasury conducted these investigations. Before that, the Office of Emergency Planning/Preparedness conducted these investigations. USDOC, BIS, Section 232 Investigations Program Guide, June 2007, 15–21.

[6] According to CRS, the actions taken included license fees, embargos (on petroleum), and voluntary restraint agreements. None of these actions, which all predate the formation of the World Trade Organization (WTO), were in the form of tariffs. Before 2016, the last time a President took action under section 232 was in 1983 on imports of certain machine tools. CRS, “Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962,” updated May 23, 2019; CRS, Section 232 Investigations, April 2, 2019, 33–34, 38–39.

[7] 82 Fed. Reg. 19205 (April 26, 2017); 82 Fed. Reg. 21509 (May 9, 2017); 83 Fed. Reg. 24735 (May 30, 2018); 83 Fed. Reg. 35204 (July 25, 2018); 84 Fed. Reg. 8503 (March 8, 2019).

[8] USDOC, BIS, The Effect of Imports of Steel, January 11, 2018, 5; USDOC, BIS, The Effect of Imports of Aluminum, January 17, 2018, 5.

[9] USDOC, BIS, The Effect of Imports of Steel, January 11, 2018, 4–5, 16; USDOC, BIS, The Effect of Imports of Aluminum, January 17, 2018, 4, 15; Proclamation 9704, 83 Fed. Reg. 11619 and Proclamation 9705, 83 Fed. Reg. 11625 (both March 8, 2018).

[10] Other risk factors for aluminum include the U.S. industry being “almost totally reliant on foreign producers of primary aluminum” and being “at risk of becoming unable to satisfy existing national security needs or respond to a national security emergency that requires a large increase in domestic production.” Other risk factors for steel include “the level of imports” and “the potential impact of further plant closures on capacity needed in a national emergency.” USDOC, BIS, The Effect of Imports of Steel, January 11, 2018, 5; USDOC, BIS, The Effect of Imports of Aluminum, January 17, 2018, 5.

[11] Proclamation 9704, 83 Fed. Reg. 11619, and Proclamation 9705, 83 Fed. Reg. 11625 (both March 8, 2018).

[12] The tariffs were announced on March 8 and went into effect March 23. All tariffs discussed in this chapter are ad valorem duties unless otherwise noted. USDOC, BIS, The Effect of Imports of Steel, January 11, 2018, 18, 21–22; USDOC, BIS, The Effect of Imports of Aluminum, January 17, 2018, 18, 20; Proclamation 9704, 83 Fed. Reg. 11619, and Proclamation 9705, 83 Fed. Reg. 11625 (both March 8, 2018); CBP, Section 232 Tariffs on Aluminum and Steel (accessed June 19, 2019). Later the President increased the section 232 tariffs on one trading partner—Turkey—to 50 percent for steel products, effective August 13, 2018. The rationale behind this included the following points: (1) the Secretary recommended that not all countries should receive the same treatment; (2) Turkey is a major steel supplier to the United States; and (3) the Secretary advised the President that “this adjustment will be a significant step toward ensuring the viability of the domestic steel industry.” The President lowered these tariffs to 25 percent effective May 21, 2019, on the grounds that “imports of steel articles from Turkey have declined by 48 percent in 2018, with the result that the domestic industry’s capacity utilization has improved.” Proclamation 9772, 83 Fed. Reg. 40429 (August 10, 2018); Proclamation 9886, 84 Fed. Reg. 23421 (May 21, 2019).

[13] Proclamation 9704, 83 Fed. Reg. 11619, and Proclamation 9705, 83 Fed. Reg. 11625 (both March 8, 2018)

[14] Proclamation 9704, 83 Fed. Reg. 11619, and Proclamation 9705, 83 Fed. Reg. 11625 (both March 8, 2018).

[15] Proclamation 9704, 83 Fed. Reg. 11619, and Proclamation 9705, 83 Fed. Reg. 11625 (both March 8, 2018).

[16] Proclamation 9704, 83 Fed. Reg. 11619, and Proclamation 9705, 83 Fed. Reg. 11625 (both March 8, 2018); Proclamation 9710, 83 Fed. Reg. 13355, and Proclamation 9711, 83 Fed. Reg. 13361 (March 22, 2018).

[17] Mexico and Canada were temporarily excluded from the section 232 tariffs in the first proclamations on aluminum and steel (9704 and 9705) issued on March 8, 2018, while the other five trading partners were excluded in subsequent proclamations (9710 and 9711) issued on March 22, 2018. Proclamation 9704, 83 Fed. Reg. 11619, and Proclamation 9705, 83 Fed. Reg. 11625 (both March 8, 2018); Proclamation 9710, 83 Fed. Reg. 13355 (March 22, 2018); Proclamation 9711, 83 Fed. Reg. 13361 (March 22, 2018).

[18] Proclamation 9704, 83 Fed. Reg. 11619, and Proclamation 9705, 83 Fed. Reg. 11625 (both March 8, 2018); Proclamation 9710, 83 Fed. Reg. 13355, and Proclamation 9711, 83 Fed. Reg. 13361 (both March 22, 2018); Proclamation 9739, 83 Fed. Reg. 20677, and Proclamation 9740, 83 Fed. Reg. 20683 (both April 30, 2018); Proclamation 9758 83 Fed. Reg. 25849, and Proclamation 9759, 83 Fed. Reg. 25857 (both May 31, 2018).

[19] Section 232 tariffs remained suspended until May 31, 2018. Proclamation 9710, 83 Fed. Reg. 13355, and Proclamation 9711, 83 Fed. Reg. 13361 (both March 22, 2018); Proclamation 9740, 83 Fed. Reg. 20683, and Proclamation 9739, 83 Fed. Reg. 20677 (both April 30, 2018).

[20] Proclamation 9758, 83 Fed. Reg. 25849, and Proclamation 9759, 83 Fed. Reg. 25857 (both May 31, 2018).

[21] Proclamation 9710, 83 Fed. Reg. 13355, and Proclamation 9711, 83 Fed. Reg. 13361 (both March 22, 2018); Proclamation 9740, 83 Fed. Reg. 20683, and Proclamation 9739, 83 Fed. Reg. 20677 (both April 30, 2018).

[22] Proclamation 9758, 83 Fed. Reg. 25849, and Proclamation 9759, 83 Fed. Reg. 25857 (May 31, 2018); CBP, Section 232 Tariffs on Aluminum and Steel (accessed June 21, 2019).

[23] Section 232 tariffs remained suspended until May 31, 2018. Proclamation 9710, 83 Fed. Reg. 13355, and Proclamation 9711, 83 Fed. Reg. 13361 (both March 22, 2018); Proclamation 9740, 83 Fed. Reg. 20683, and Proclamation 9739, 83 Fed. Reg. 20677 (both April 30, 2018).

[24] Proclamation 9759, 83 Fed. Reg. 25857 (May 31, 2018).

[25] Proclamation 9710, 83 Fed. Reg. 13355 (March 22, 2018); Proclamation 9758, 83 Fed. Reg. 25849 (May 31, 2018).

[26] Proclamation 9704, 83 Fed. Reg. 11619, and Proclamation 9705, 83 Fed. Reg. 11625 (both March 8, 2018); CBP, Section 232 Tariffs on Aluminum and Steel (accessed June 19, 2019); Proclamation 9739, 83 Fed. Reg. 20677, and Proclamation 9740, 83 Fed. Reg. 20683 (both April 30, 2018).

[27] Imports of both steel products and aluminum were officially excluded from section 232 tariffs effective May 19, 2019. Proclamation 9894, 84 Fed. Reg. 23987 (May 23, 2019); Proclamation 9893, 84 Fed. Reg. 23983 (May 26, 2019).

[28] Proclamation 9710, 83 Fed. Reg. 13355, and Proclamation 9711, 83 Fed. Reg. 13361 (both March 22, 2018); Proclamation 9740, 83 Fed. Reg. 20683, and Proclamation 9739, 83 Fed. Reg. 20677 (both April 30, 2018).

[29] Proclamation 9710, 83 Fed. Reg. 13355, and Proclamation 9711, 83 Fed. Reg. 13361 (both March 22, 2018); Proclamation 9740, 83 Fed. Reg. 20683, and Proclamation 9739, 83 Fed. Reg. 20677 (both April 30, 2018).

[30] Proclamation 9740, 83 Fed. Reg. 20683 (April 30, 2018). In late August 2018, the President authorized the Secretary to establish procedures for both steel and aluminum articles consistent with the relevant proclamations, to grant relief from certain quantitative restrictions (e.g., the above-discussed quotas established for Argentina, Brazil, and South Korea) in limited circumstances for certain subheadings of the Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (HTS). These includes steel and aluminum articles “for which the Secretary determines there is a lack of sufficient domestic production of comparable products, or for specific national security-based considerations.” Proclamation 9776, 83 Fed. Reg. 45019, and Proclamation 9777, 83 Fed. Reg. 45025 (both August 29, 2018).

[31] Proclamation 9739, 83 Fed. Reg. 20677 (April 30, 2018).

[32] Proclamation 9704, 83 Fed. Reg. 11619, and Proclamation 9705, 83 Fed. Reg. 11625 (both March 8, 2018).

[33] Proclamation 9704, 83 Fed. Reg. 11619, and Proclamation 9705, 83 Fed. Reg. 11625 (both March 8, 2018).

[34] Eligible parties requesting exclusions must provide a description of the requested excluded article and the amount of articles requested to be exempt. Eligible parties may comment on these requests. U.S. manufacturers may file objections to these requests, if supported by factual information, on (1) the steel or aluminum articles they manufacture, (2) their production capabilities at domestic manufacturing facilities, and (3) the availability and delivery time of the articles domestically manufactured relative to the specific articles subject to the exclusion request. Exclusion requestors may provide additional information in response to the comments. Commerce initially published the exclusion requests and comments on regulations.gov under docket number BIS-2018-0002 for aluminum and docket number BIS-2018-0006 for steel. Eligible parties who are granted exclusions are given an exclusion number to be used with U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP). Further updates to the process were published in September 2018, when Commerce responded to comments about the exclusion process it had established. USDOC, BIS, “Submissions of Exclusion Requests,” September 11, 2018. In June 2019, Commerce announced the creation of the “232 Exclusions Portal” (https://232app.azurewebsites.net/steelalum) to handle requests, taking the place of regulations.gov in the ongoing exclusion request process. USDOC, BIS, “Requirements for Submissions Requesting Exclusions,” March 19, 2018; USDOC, BIS, “Implementation of New Commerce Section 232 Exclusions Portal,” June 10, 2019; USDOC, BIS, “Section 232 National Security Investigation of Aluminum Imports,” June 20, 2019; USDOC, BIS, “Section 232 National Security Investigation of Steel Imports,” June 18, 2019.

[35] USDOC, BIS, “Requirements for Submissions Requesting Exclusions,” March 19, 2018.

[36] Ross, Statement before the U.S. Senate Committee on Finance, June 20, 2018.

[37] McDaniel and Parks, “Growing Backlog, Inconsistent Rulings,” January 28, 2019; QuantGov, “Tariff Exclusions: Section 232 Tariffs” (accessed July 19, 2019); Unterman, Samuelson, and Nguyen, “FOIA Documents Unmask the Tariff Exemption Process,” November 5, 2018.

[38] CRS also reported that Commerce denied about 500 requests each for steel and aluminum. CRS, Section 232 Investigations, April 2, 2019, 10.

[39] See, e.g., Bown, “Trump’s Steel and Aluminum Tariffs,” March 8, 2018; Breuninger, “Canada Announces Retaliatory Tariffs,” May 31, 2018; WTO, Dispute Settlement: The Disputes, DS544 (China); DS547 (India); DS548 (EU); DS550 (Canada); DS551 (Mexico); DS552 (Norway); DS554 (Russia); DS556 (Switzerland); DS564 (Turkey) (accessed June 26, 2019). According to the WTO, “safeguard measures are defined as ‘emergency’ actions with respect to increased imports of particular products, where such imports have caused or threaten to cause serious injury to the importing Member’s domestic industry.” The WTO Agreement on Safeguards governs their use by WTO members. WTO, Agreement on Safeguards, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/safeg_e/safeint.htm.

[40] These cases were filed between April and August 2018. A number of other trading partners signed on as third parties to each of these disputes. The disputes filed by Mexico and Canada were withdrawn in May 2019, after these countries reached an agreement with the United States. WTO, Dispute Settlement: The Disputes, DS544 (China); DS547 (India); DS548 (EU); DS550 (Canada); DS551 (Mexico); DS552 (Norway); DS554 (Russia); DS556 (Switzerland); DS564 (Turkey) (accessed June 26, 2019). For further information on these WTO disputes, see USITC, The Year in Trade 2018, 2019.

[41] All the consultation requests listed specific articles of the WTO Agreement on Safeguards with which the trading partner believes the U.S. section 232 tariffs are inconsistent; however, the articles identified in each complaint varied. All the consultation requests also alleged that the U.S. action was inconsistent with certain GATT articles (which varied by complaint)—including, for example, articles I:1, II:1(a and b), and X:3(a). Some complaints also alleged that the United States is in violation of article XVI:4 of the WTO Agreement. WTO, Dispute Settlement: The Disputes: DS544 (China); DS547 (India); DS548 (EU); DS550 (Canada); DS551 (Mexico); DS552 (Norway); DS554 (Russia); DS556 (Switzerland), and DS564 (Turkey) (accessed June 26, 2019). Mexico also alleged that the U.S. actions under section 232 are a breach of certain NAFTA obligations. Government of Mexico, “Decreto por el que se modifica la Tarifa” (Presidential decree modifying the tariff), June 5, 2018. Canada and Mexico settled or terminated their disputes with the United States on May 23, 2019, and May 28, 2019, respectively. WTO, Dispute Settlement: The Disputes: DS550 (Canada) and DS551 (Mexico) (accessed September 5, 2019).

[42] See, e.g., EC, “Commission Implementing Regulation (EC) 2018/724,” October 31, 2017; Government of Turkey, “Immediate Notification under Article 12.5 of the Agreement on Safeguards,” May 21, 2018; Government of China, “Immediate Notification under Article 12.5 of the Agreement on Safeguards: China,” April 3, 2018.

[43] USDOC, ITA, Current Foreign Retaliatory Actions (accessed June 28, 2019); Brew et al., “Latest U.S. Trade Actions/Tariffs and Other Countries Retaliatory Measures” (accessed June 26, 2019); Sandler, Travis, & Rosenberg, Tariff Actions Resource Page, updated July 1, 2019. In addition, Japan notified the WTO of its intent to impose additional duties on certain U.S. products, but as of October 1, 2019, had not done so. Government of Japan, “Immediate Notification under Article 12.5 of the Agreement on Safeguards,” May 18, 2018; USDOC, ITA, Current Foreign Retaliatory Actions (accessed July 17, 2019).

[44] There was one exception. In its request for consultations against Mexico, the United States mentioned only Article I:1 of the GATT. The U.S. government gave a more detailed explanation of the basis for its complaints in the majority of its requests for consultations. This includes the one against the EU, which states that “{t}he additional duties measure appears to be inconsistent with: Article I:1 of the GATT 1994, because it fails to extend to products of the United States an advantage, favor, privilege or immunity granted by the European Union with respect to customs duties and charges of any kind imposed on or in connection with the importation of products originating in the territory of other Members; and Article II:1(a) and (b) of the GATT 1994 because it accords less favorable treatment to products originating in the United States than that provided for in the European Union’s schedule of concessions.” WTO, Dispute Settlement: The Disputes: Request for Consultations by the United States, DS557 (Canada), DS558 (China), DS559 (EU), DS560 (Mexico). DS5561 (Turkey), DS566 (Russia), DS585 (India) (accessed September 5, 2019). The United States settled or terminated its disputes with Canada on May 23, 2019, and with Mexico on May 28, 2019. WTO, Dispute Settlement: The Disputes: DS557 (Respondent: Canada) and DS560 (Mexico) (accessed September 5, 2019).

[45] Canada noted that it chose items that “support political advocacy in the U.S., while also mitigating the potential negative impacts on the Canadian economy.” Government of Canada, “Canada Order SOR/2018-152,” and “Canada Order SOR/2018-153,” both June 28, 2018; Government of Canada, Department of Finance, “Updated–Countermeasures in Response to Unjustified Tariffs,” May 23, 2019.

[46] Government of Canada, “Canada Order SOR/2019-144,” May 19, 2019; Government of Canada, “Canada Order SOR/2019-143,” May 19, 2019; Government of Canada, Department of Finance, “Updated—Countermeasures in Response to Unjustified Tariffs,” May 23, 2019.

[47] Government of China, “Immediate Notification under Article 12.5,” April 3, 2018; Government of China, Ministry of Finance, “Taxation Committee [2018] No. 13,” April 1, 2018.

[48] The EU has scheduled the second stage of duties to be applied on March 23, 2021, “or upon the adoption by, or notification to, the WTO Dispute Settlement Body of a ruling that the United States' safeguard measures are inconsistent with the relevant provisions of the WTO Agreement, if that is earlier.” EC, “Commission Implementing Regulation (EC) 2018/724,” May 17, 2018.

[49] Government of Mexico, “Decreto por el que se modifica la Tarifa” (Presidential decree modifying the tariff), June 5, 2018.

[50] Government of Mexico, “Decreto por el que se modifica la Tarifa” (Presidential decree modifying the tariff), June 5, 2018.

[51] Government of Mexico, “Decreto que modifica el diverso por el que se modifica la Tarifa” (Presidential decree that removes the modified tariff), May 20, 2019.

[52] Presidential Memorandum on the Actions by the United States Related to the Section 301 Investigation, March 22, 2018; Trade Act of 1975, 19 U.S.C. §§ 2411–2417 (https://legcounsel.house.gov/Comps/93-618.pdf).

[53] Trade Act of 1975, 19 U.S.C. §§ 2411–2417, section 301 (b).

[54] Trade Act of 1975, 19 U.S.C. §§ 2411–2417, section 301 (c).

[55] Presidential Memorandum for the United States Trade Representative, August 14, 2017. In addition, section 303 of the Trade Act of 1975 requires USTR to “request consultations with the foreign country concerned regarding the issues involved in such investigation.” Trade Act of 1975, 19 U.S.C. §§ 2411–2417.

[56] 83 Fed. Reg. 14906 (April 6, 2018). See also USTR, Findings of the Investigation into China’s Acts, March 22, 2018; USTR, “Section 301 Fact Sheet,” March 2018.

[57] Presidential Memorandum Related to the Section 301 Investigation, 83 Fed. Reg. 13099 (March 27, 2018).

[58] Most products on the section 301 tariff lists are listed at the HTS 8-digit subheading level. However, tranches 3 and 4 include “full and partial tariff subheadings.” 83 Fed. Reg. 28710 (June 20, 2018); 83 Fed. Reg. 40823 (August 16, 2018); 83 Fed. Reg. 47974 (September 21, 2018); 83 Fed. Reg. 49753 (September 28, 2018); 84 Fed. Reg. 20496 (May 9, 2019); 84 Fed. Reg. 26930 (June 10, 2019); 84 Fed. Reg. 22564 (May 17, 2019); 84 Fed. Reg. 43304 (August 20, 2019); 84 Fed. Reg. 45821 (August 30, 2019). USITC provides a list of modifications to HTS and links to corresponding notifications on its website at https://www.usitc.gov/modifications_harmonized_tariff_schedule.htm.

[59] Based on U.S. imports for consumption from China. USITC DataWeb/USDOC (accessed July 31, 2019).

[60] Goods on the water as of May 10 had until June 15, 2019, to enter the United States at the 10 percent duty rate. 84 Fed. Reg. 20496 (May 9, 2019); 84 Fed. Reg. 26930 (June 10, 2019).

[61] USTR, China Section 301—Tariff Actions (accessed July 3, 2019).

[62] 84 Fed. Reg. 43304 (August 20, 2019); 84 Fed. Reg. 45821 (August 30, 2019).

[63] Most products are listed at the HTS 8-digit subheading level. However, tranches 3 and 4 include “full and partial tariff subheadings.”

[64] See, e.g., 83 Fed. Reg. 14906; 83 Fed. Reg. 28710 (June 20, 2018); USTR, China Section 301—Tariff Actions (accessed July 3, 2019).

[65] 83 Fed. Reg. 28710 (June 20, 2018); 83 Fed. Reg. 40823 (August 16, 2018); 83 Fed. Reg. 47974 (September 21, 2018).

[66] 83 Fed. Reg. 67463 (December 28, 2018).

[67] USITC calculations, 2019 HTS item count, May 1, 2019.

[68] These fall into three groupings: (1) subheadings from section XVI (chapters 84 and 85), which cover items including nuclear reactors, machinery, laboratory equipment, and parts; (2) subheadings from section XVII (chapters 86–89), which cover “vehicles, aircraft, vessels and associated transport equipment”; and (3) subheadings from chapter 90, which cover items including certain navigational equipment, electromagnetic items, and medical and dental devices. 83 Fed. Reg. 28710 (June 20, 2018); USITC, Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States 2019, Revision 8, July 2019.

[69] The plastic and plastic articles are classified in HTS chapter 39. The advanced technology and machinery products are primarily classified in HTS chapters 84–87. There are also other products on this list, including some from HTS chapter 90, and some additional steel and aluminum products are classified in in HTS chapters 73 and 76. 83 Fed. Reg. 40823 (August 16, 2019); USITC, Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States 2019: Revision 8, July 2019.

[70] 83 Fed. Reg. 47974 (September 21, 2018); 83 Fed. Reg. 49753 (September 28, 2018); USTR, $200 Billion Trade Action (List 3): Tariff List (accessed July 18, 2019).

[71] Government of China, Ministry of Commerce, “Announcement 2018 no. 69,” September 18, 2018.

[72] WTO, “Dispute Settlement: The Disputes, United States—Tariff Measures on Certain Goods from China I and II, Request for Consultations by China (DS543 and DS565)” (accessed July 16, 2019). On September 2, 2019, China filed a third request for consultations against U.S. section 301 tariffs citing the same agreements and articles as DS543 and DS565WTO, “Dispute Settlement: The Disputes, United States—Tariff Measures on Certain Goods from China III, Request for Consultations by China: (DS587)” (accessed September 5, 2019).

[73] These additional duties are applied at the HTS 8-digit subheading level.

[74] China included some products in more than one tranche. Government of China, Ministry of Finance, “Taxation Committee Announcement [2018] No. 5,” June 16, 2018; Government of China, Ministry of Commerce, “Announcement [2018] No. 64,” August 8, 2018; Government of China, Ministry of Commerce, “Announcement [2018] No. 69,” September 18, 2018; Government of China, Ministry of Finance, “Taxation Committee Announcement [2019] No. 4,” August 23, 2019.

[75] Government of China, Ministry of Finance, “Taxation Committee Announcement [2019] No. 2,” May 13, 2019. Reportedly, exclusion requests were accepted between June 3 and July 5, 2019, for lists 1 and 2 and were expected to be accepted between September 2 and October 18, 2019, for list 3. Sandler Travis, Tariff Actions Resource Page, July 8, 2019.

[76] The estimated value is based on the Chinese government’s estimates for tranche 1 and 2 and Bloomberg’s estimate for tranche 3. See table ST.4 for more information on this estimate. China imposed additional duties on some products (at the 8-digit subheading level) in response to both U.S. section 232 and section 301 tariff actions. USDOC, ITA, Current Foreign Retaliatory Actions (accessed July 9, 2019); Government of China, Ministry of Finance, “Taxation Committee Announcement [2018] No. 5,” June 16, 2018; Government of China, Ministry of Commerce, “Announcement [2018] No. 64,” August 8, 2018; Government of China, Ministry of Commerce, “Announcement [2018] No. 69,” September 18, 2018); Sandler Travis, China 301 List 1; Sandler Travis, China 301 List 2, Version 2; Sandler Travis, China 301 Lists 3.1–3.4 (all accessed July 9, 2019); Curran, Mayeda, and Leonard, “China Strikes $60 Billion of U.S. Goods,” September 17, 2018; Government of China, Ministry of Finance, “Taxation Committee Announcement [2018] No. 13,” April 1, 2018; Curran, Mayeda, and Leonard, “China Strikes $60 Billion of U.S. Goods,” September 17, 2018.

[77] Based on Chinese imports from the United States. IHS, Global Trade Atlas database (accessed October 28, 2019).

[78] Government of China, Ministry of Finance, “Taxation Committee Announcement [2018] No. 5,” June 16, 2018.

[79] Soybeans, not for seed, are classified under HS 1201.90. USITC DataWeb/USDOC (accessed September 5, 2019).

[80] Tariffs rose to 25 percent for list 3.1, to 20 percent for list 3.2, and to 10 percent for list 3.3. Government of China, Ministry of Commerce, “Announcement [2018] No. 69,” September 18, 2018; Sandler Travis, China 301 List 3.1–3.4 (accessed July 9, 2019); Government of China, Ministry of Finance, “The State Council Customs Tariff Commission Issued a Notice,” May 13, 2019.