The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Freight Transportation Services and U.S. Merchandise Imports

COVID-19 Disruptions in Maritime Shipping and Air Freight

Maritime and air freight transport provide the essential transportation services that enable global merchandise trade, including U.S. imports.[1] Beginning in early 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted maritime shipping and air freight services, leading to canceled sailings and flights, port delays, and container shortages. These disruptions were particularly profound for U.S. imports originating from Northeast Asia. Combined with COVID-19 related changes in demand, the disruptions increased volatility in maritime and air freight rates across regions and caused significant delays in the delivery of U.S. merchandise imports. This chapter is divided into two parts: the first part discusses the nature of shipping disruptions during the pandemic, while the second part examines the above-mentioned effects on freight rates, shipping modes, and arrival times of U.S. merchandise imports.

The disruptions in maritime shipping related to the COVID-19 pandemic and their effects on merchandise imports can be divided into two distinct halves.[2] In the first half of 2020, U.S. maritime container imports declined 7.0 percent, by volume, compared to the same period in 2019, while in the second half of 2020 there was a large increase in container imports.[3] Compared to the same period in 2019, containerized imports rose 9.5 percent, by volume, in the second half of 2020, and year-over-year grew 16.4 percent in the fourth quarter.[4]

The notable increase in the volume of U.S. merchandise imports in the second half of 2020 stimulated a rise in imports of associated maritime shipping and port services. U.S. merchandise trade data indicate that the increase in U.S. imports of maritime freight services in the third and fourth quarters of 2020 largely was due to a sharp rise in trade with Asia, especially China.[5] In the second half of 2020, the value of U.S. imports of maritime freight transport services (which relate to the transport of U.S. goods imports by foreign maritime vessels) increased by 16.5 percent compared to the same period in 2019.[6] Similarly, U.S. exports of port services (which relate to the purchase of goods and services by foreign vessels arriving at U.S. ports) rose 3.5 percent year-over-year in the second half of 2020.

Reduced Capacity for Container Shipping

The contraction of U.S. merchandise trade in the first half of 2020, coupled with a slowdown in manufacturing in China, led container shipping firms to cancel scheduled sailings (called “blank sailings”) and consolidate shipping routes to focus service on major ports in the first half of 2020.[7] This, in turn, permitted shipping lines to lower costs and mitigate a downward pressure on freight rates due to overcapacity.[8] For example, in June 2020, the three largest container shipping alliances (THE Alliance, 2M Alliance, and Ocean Alliance) announced their intent to cancel 126 scheduled sailings between Asia and North America through August 2020, and another 94 sailings between Asia and Europe.[9] Container shipping firms canceled more than 1,000 voyages in the first six months of 2020 (figure ST.1).[10] These reductions stabilized spot rates for maritime freight in mid-2020 slightly above their 2019 levels, as firms at the time anticipated reduced international trade and a slower economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic.[11] As discussed in more detail below, maritime freight rates rose substantially in the second half of 2020 as trade recovered and outstripped shipping capacity.

In mid-2020, increased economic activity and sharply rising consumer demand led to a recovery in merchandise trade which in turn caused capacity shortages in the maritime freight sector. During that time, container shipping firms struggled to restore capacity to previous levels.[12] For example, U.S. imports from Asia were nearly 30 percent higher in December 2020 than in December 2019, precipitated by the surge in online purchases.[13] The number of shipping containers in circulation during the second half of 2020 was insufficient to meet customer storage demands and higher than anticipated consumer demand for imports.[14] The unexpected recovery in demand shocked the distribution system and firms had trouble getting products to customers.[15] Maersk, a major global shipping firm, had forecast a sustained period of low demand in early 2020.[16] However, by the fourth quarter, container shipping firms were operating at nearly full capacity. Blank sailings declined from 21 percent of all voyages in May 2020 to 1 percent by October 2020.[17] The recovery in demand for international maritime freight transportation caused container vessels to operate at near maximum capacity, which resulted in a depletion of shipping container inventory at major ports.[18]

This container shortfall was exacerbated by the misallocation of containers across the distribution system. During the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, demand for containers dropped along with orders for new container production, and some containers were used as long-term storage.[19] U.S. demand for containerized imports that increased to a greater degree than expected in the second half of 2020, exceeded the demand for U.S. eastbound exports as well as outpaced shipping container manufacturing.[20] This, in turn, caused the repositioning of containers to transport imported goods from Asia (especially China) to become a priority for shippers.[21] The container shortage was further exacerbated by an increase in the turnaround times for containers (the time it takes a container to complete a trip and be ready for reloading) due to rising ship bottlenecks at ports, particularly in the high-volume trade lanes between northern Asia and the U.S. West Coast.[22]

According to one estimate, 30 to 35 percent of all containers exported from the United States remained empty and were needed to meet container demand in Asia for exports to the United States.[23] In addition, ocean carriers received greater financial incentive for returning empty containers to Asia than for transporting U.S. containerized exports to Asian markets.[24] The container shortage increased costs for U.S. importers (as leasing rates rose) and has been cited as an impediment to U.S. exports, particularly of agricultural goods.[25]

Effects of COVID-19 on Transportation Personnel

High COVID-19 infection rates among port workers negatively impacted port operations, which decreased the amount of cargo that could move to and from ships.[26] Consequently, ports became bottlenecks with shipping container backlogs that delayed loading and offloading merchandise. Updated health policies and working conditions also may have decreased port productivity. Moreover, labor shortages impacted global supply chains.[27] For example, onshore transportation systems (including rail and trucks) faced labor shortages that delayed the availability of goods and increased costs.[28]

The COVID-19 pandemic further disrupted the flow of goods by halting international travel for maritime workers and increasing maritime personnel costs. As the COVID-19 outbreak became a global pandemic, many governments imposed travel restrictions and certain quarantine procedures that reduced labor mobility in the maritime sector.[29] The International Labour Organization estimated that 800,000 seafarers were unable to embark on or disembark from their vessels in 2020.[30] Starting in May 2020, this problem abated as several countries allowed firms to charter flights in pre-approved “safe transit corridors” to allow seafarers to travel from their home countries to select ports in order to relieve other seafarers.[31] These and other factors increased labor expenses, particularly hardship pay to compensate workers stranded on vessels, higher travel costs to reposition workers, and COVID-19 testing and quarantine expenses.[32] One source estimated that the higher labor-related expenses caused maritime personnel costs to rise 6.2 percent in 2020.[33]

In 2020, air freight experienced two different, but related impacts associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. The first, and most significant, impact was a sharp decrease in capacity to transport freight in the cargo holds of passenger aircraft (“belly cargo”) due to cancelled flights. The second impact was a pandemic-related increase in air freight demand for certain merchandise imports, primarily for products like personal protective equipment (PPE).[34] These resulted in a steep increase in air freight rates compared to 2019, as well as increased volatility in these rates compared to previous years. These impacts varied by region, however, with Asia-North America routes the most affected (as explained below).

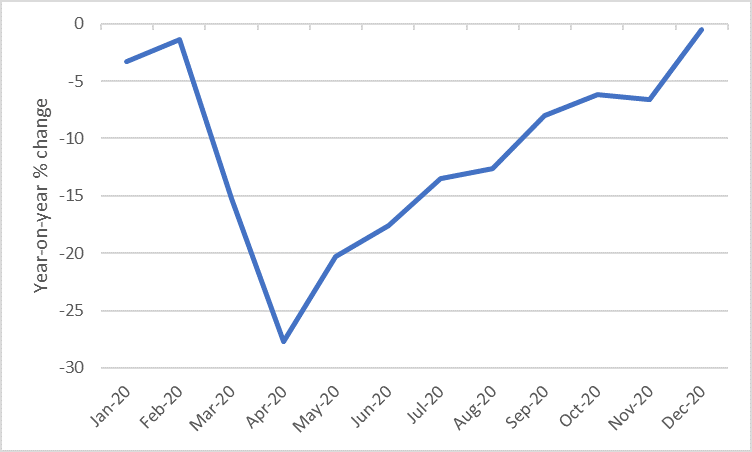

Global air freight volumes experienced a substantial decline beginning in early 2020 as measured by air cargo tonne-kilometers (CTK).[35] For 2020 as a whole, global CTKs fell 10.6 percent, the largest decline since at least 1990, compared to a 6 percent decline in global merchandise trade in 2020.[36] Total CTKs reached their lowest point in April 2020, early in the pandemic, before rising again through December 2020 and recovering to their pre-pandemic monthly levels (figure ST.2).[37] This pattern also varied by region. While all routes experienced a decline in CTKs beginning in early 2020, cargo shipments on routes to and from North America rose above 2019 monthly levels as early as May 2020, while shipments on routes to and from Latin America remained below 2019 levels at the end of 2020. By the end of 2020, shipments on major routes including North America, Asia, the Middle East, and Europe all rose above their January 2020 levels, while smaller routes to Latin America were still below their previous levels.[38]

Figure ST.2 Global cargo tonne-kilometers (CTKs), monthly, year-on-year percent change

Source: ICAO, “Air Transport Monthly Monitor,” February 2021.

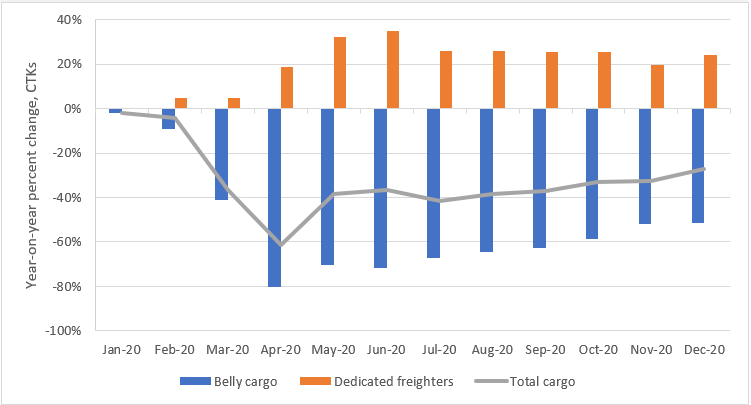

These trends in air cargo shipments were largely driven by changes in the availability of belly cargo capacity on passenger planes. Beginning in February 2020, many countries announced travel restrictions to mitigate transmission of COVID-19, and passenger air travel was severely curtailed. This reduced the volume of U.S. air travelers (both domestic and international), which had been growing steadily since at least 2017. The volume fell precipitously in early 2020—from 78.7 million in February to 3.0 million in April 2020—before beginning a slow recovery starting in May 2020.[39] Belly cargo accounted for about 60 percent of total international CTKs before the pandemic (with dedicated freighters supplying the balance), though by December of 2020 it only accounted for one third. Air carriers increased the number of dedicated freighters they used in 2020 compared to 2019 to partially offset the decline in belly cargo, but not by enough to maintain previous levels of total air cargo supply (figure ST.3).[40] Several reports noted that some airlines converted passenger aircraft into fully cargo aircraft, with some conversions removing interiors to create more space or retrofitting older airplanes, and other (quicker) conversions simply strapping packages into existing seats.[41] Increases in air freight rates (discussed in more detail below) also induced airlines to move towards cargo in the face of reduced revenue from passenger fares to shore up their balance sheets.[42]

Figure ST.3 Year-on-year percent change in cargo tonne-kilometers (CTKs) for belly cargo, dedicated freight, and total air cargo, 2020 compared to 2019

Source: IATA, “Air Cargo Market Analysis,” December 2020.

Domestic U.S. air travel recovered more strongly in 2020 than international travel. Domestic air passengers increased 2,264.3 percent from its lowest point in April 2020 to December 2020, while the number of international passengers increased 872.0 percent over the same period.[43] This points to a weaker recovery in belly cargo capacity on international routes than for domestic routes. This was compounded by the slower rate that wide-body jets returned to the air. These airplanes carry more passengers and predominate on international routes but are also better suited to carrying freight.[44]

A sudden and sharp increase in demand during early 2020 for international shipments of PPE resulted in a surge in demand for international air cargo delivery services. Demand for PPE spiked in the first half of 2020, with orders requiring fast fulfillment times, leading shippers to move these products via air cargo.[45] As PPE stockpiles were built, which coincided with the end of the first wave of COVID-19 infections in the United States, the volume of PPE shipped via air cargo fell. Lower shipments in turn put downward pressure on the temporarily high freight rates.[46] The surge in PPE trade can be seen in the trade statistics described in more detail below. The percentage of goods moved via air cargo in the textile and apparel sector (which includes masks, gowns, and other PPE) surged in 2020 compared to prior years.[47]

In the second half of 2020, by contrast, there was a rise in the share and level of electronic products shipped via air cargo, as consumers shifted their spending away from services and towards durable goods. During that time, many consumers were looking to outfit home offices during pandemic-related workplace closures and increased their use of e-commerce channels.[48]

Impacts of Shipping Disruptions and Merchandise Imports from Northeast Asia

The remainder of this chapter examines the impacts of shipping disruptions described above on shipping costs, the cost of goods, and the main transportation modes and shipping routes used by shippers. It also discusses the types of products most affected by delays and the impact of these shipping disruptions on small importers. This section examines the overall impact as well as the effects by sector. However, individual firms and industries have had widely varying experiences, with some experiencing only minor effects and others much more significant impacts than the aggregate data show.

The main purpose of this section is to provide information on trends in 2020, which as appropriate is placed within a five-year context to show the extent to which these trends deviated from historical norms. This chapter does not quantitatively assess the extent to which shipping disruptions decreased the volume of imports from levels that would have otherwise occurred. Given the unique circumstances of 2020, such an assessment would need to take into account a range of factors. For example, it would need to consider not only the price of freight services, but also the availability of freight and the inelasticity of demand—such as for PPE—during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in a significant increase in maritime freight costs from Northeast Asia starting in the second half of 2020.[49] In the first half of 2020, shipping prices remained relatively unchanged by COVID-19 because shipping companies canceled planned shipments (leading to blank sailings) due to the decline in global demand.[50] In June 2020, however, shipping costs began to increase due to recovering consumer demand for goods as well as container shortages and other factors described above.[51] According to the online international freight marketplace, Freightos, the weekly index price to ship a container from China to the North American West Coast increased 178 percent or $2,676 per container from January to December 2020 (figure ST.4).[52] Increased transportation costs affected firms by forcing some firms out of the market and altering inventory management decisions.[53]

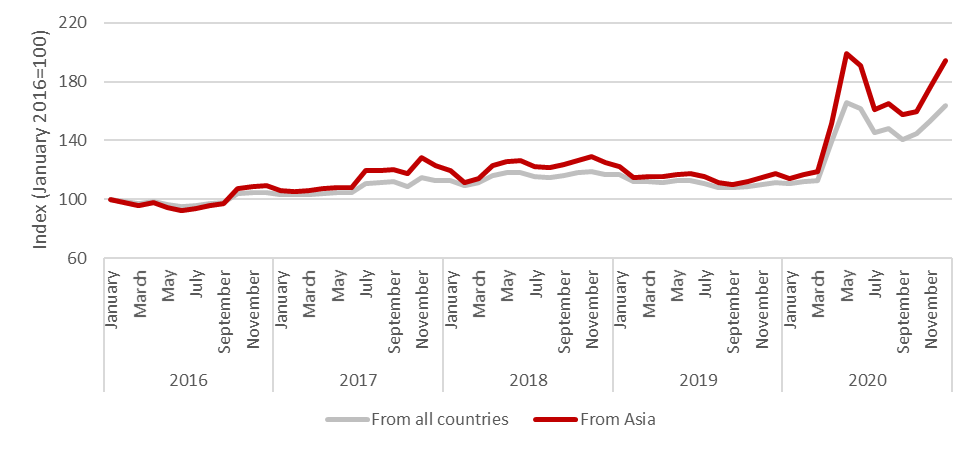

Air freight rates also increased sharply due to the contraction in air freight capacity during the pandemic. According to data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the U.S. inbound air freight price index from Asia rose 28 percent from March to April 2020 and another 31 percent from April to May 2020 (figure ST.5).[54] Though prices in the following months declined somewhat by September, a second spike occurred later in the year.[55] The Baltic Air Freight Index, which measures spot prices, reported that the cost to ship 1 kilogram of air freight rose 102 percent from Hong Kong to North America between January 2020 and December 2020.[56] Indices which measure spot prices (such as the aforementioned Baltic Air Freight Index) tend to be more volatile than prices in the long-term contracts used by dedicated air cargo firms like FedEx and UPS.[57] Prices for air cargo charters also increased in 2020 compared to 2019, but not as much as spot prices for air freight.[58]

Figure ST.5 U.S. inbound air freight price index, 2016–20

Source: USDOL, BLS, “Import/Export Price Indexes (MXP),” accessed June 14, 2021. Notes: Data are not seasonally adjusted.

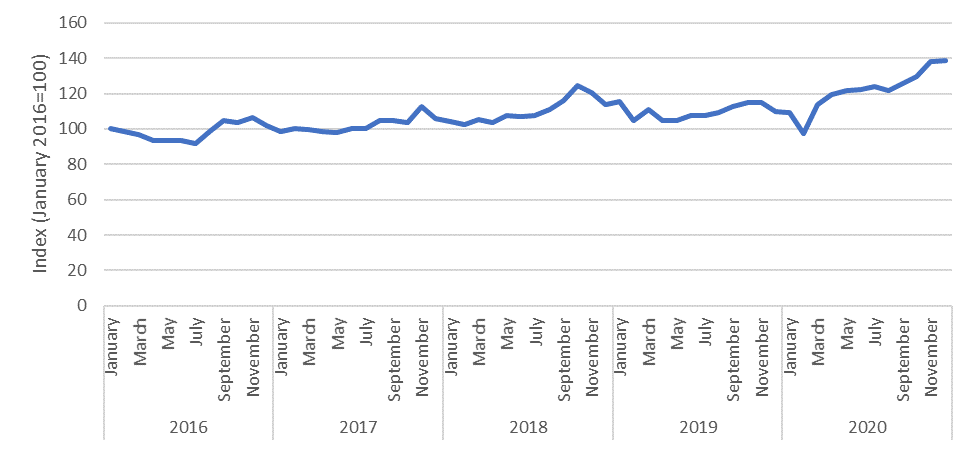

In addition to data from Freightos and BLS, changes in transportation costs can also be examined using insurance and freight costs as reported by the U.S. Census Bureau. Insurance and freight costs per kilogram (kg) of U.S. imports from Northeast Asia as reported by the U.S. Census Bureau regardless of transportation mode briefly fell in February 2020, then increased over the year (figure ST.6).[59] Insurance and freight costs per kg in December 2020 were 26 percent above December 2019 costs. Increases in transportation costs as measured by per kilogram international insurance and freight costs were more modest than the maritime and airfreight price increases as reported by Freightos and BLS. Many goods are shipped at previously arranged contract prices and a significant portion of maritime imports use bulk shipping (contract prices and bulk shipping are not captured in the above Freightos data, and air transportation, which is shown in the BLS data, represents only a small share of freight). Goods sold pursuant to previously arranged contracts may be less impacted by changes in transportation costs, and transportation costs for bulk shipments do not appear to have significantly increased until 2021.[60] This likely explains the more modest increase in transportation costs seen in the insurance and freight data than seen in the data reported by Freightos and BLS. However, some firms that needed to pay the spot prices may have incurred much larger cost increases than shown in figure ST.6.

Figure ST.6 Insurance and freight costs for U.S. imports from Northeast Asia, index of dollar/kg, January 2016–December 2020

Source: IHS Markit, “Global Trade Atlas Database,” accessed May 20, 2021; USITC DataWeb/Census, accessed August 19, 2021.

Notes: The data in this chart are based on import charges for all transport modes from Northeast Asia from DataWeb and the volume of imports in kilograms by air and vessel from official statistics in Global Trade Atlas. As import charges are not available by transport mode for these data and therefore report import charges for modes of transport other than air and vessel, these data may slightly overstate the costs of imports. However, only 6 percent of annual imports (by value) from Northeast Asia during 2016–20 did not enter via air or vessel.

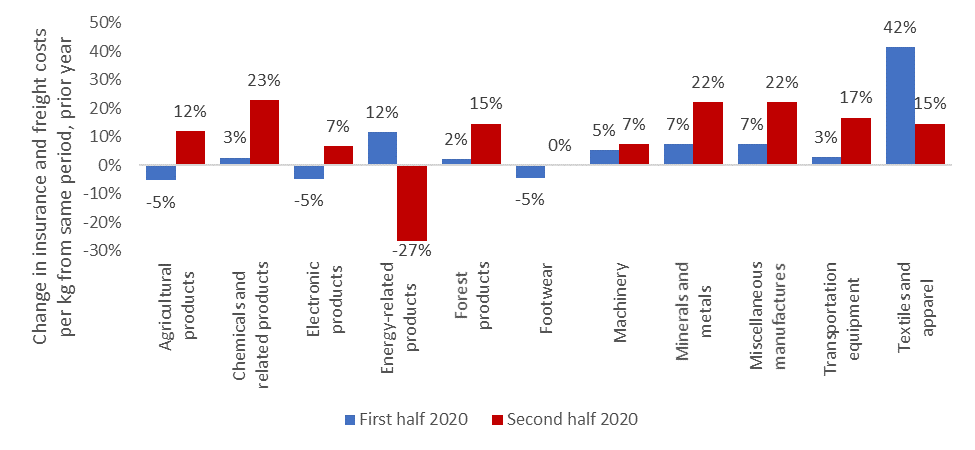

The three sectors that experienced the largest increase in insurance and freight costs from Northeast Asia, in dollars per kg, were textiles and apparel (up 25 percent from 2019), minerals and metals (up 16 percent), and chemicals and related products (up 13 percent).[61] One of the main drivers of the increase in textile and apparel shipping costs was the demand for PPE due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[62] In the spring of 2020, the United States started to import large volumes of PPE, while the rapid increase in demand for air cargo for PPE and a steep drop in passenger flights led to a significant increase in shipping costs. As a result, the increase in shipping costs for textiles and apparel was largest in the first half of the year, though increased shipping costs also continued in the second half of the year (figure ST.7). For other products, however, the increase in shipping costs was concentrated in the second half of the year,[63] with chemicals and related products (23 percent) and minerals and metals (22 percent) experiencing the largest second half cost increases.[64]

Figure ST.7 Change in insurance and freight costs per kg from same period in prior year, U.S. imports from Northeast Asia, 2020

Sources: IHS Markit, “Global Trade Atlas Database,” accessed May 20, 2021; USITC DataWeb/Census, accessed August 19, 2021.

Notes: The data in this chart are based on import charges for all transport modes from Northeast Asia from DataWeb and the volume of imports in kg by air and vessel from official statistics in Global Trade Atlas. As import charges are not available by transport mode for these data and therefore report import charges for modes of transport other than air and vessel, these data may slightly overstate the costs of imports. However, only 6 percent of annual imports (by value) during 2016–20 did not enter via air or vessel.

Shipping costs represent only a small share of the value of imports, and the increase in the share of import value accounted for by shipping costs was relatively small. The largest increase in insurance and freight costs, as a share of the landed duty-paid value of imports, was in energy-related products. Insurance and freight costs for energy-related products from Northeast Asia increased from 4.4 percent of the value of imports to 5.7 percent, though this was driven by significant price declines in energy products rather than freight cost increases.[65] The second-largest increase was in forest products, where insurance and freight costs rose from 6.9 percent of the value of imports to 7.8 percent.[66] However, these costs increased over the course of the year, with the largest increases for imports from Northeast Asia in the fourth quarter of 2020 (compared to the fourth quarter of 2019) in forest products (up from 7.0 percent of the landed duty-paid value to 8.5 percent), minerals and metals (up from 5.4 to 6.6 percent), textiles and apparel (up from 4.3 to 5.3 percent), and machinery (up from 3.5 to 4.5 percent).[67]

The shipping challenges and increased costs resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic did not result in a major change in the shipping mode used for imports from Northeast Asia in 2020, except in the textile and apparel sector. In textiles and apparel, the share of goods shipped by air freight increased from 9 percent in 2019 to 22 percent in 2020, reflecting the large volume of PPE shipped via air freight (figure ST.8).[68] While there were smaller increases in the share of goods shipped via air freight in other sectors, such as chemicals and electronic products—and certain COVID-19 related trends that encouraged more use of air freight for certain goods in these sectors—these shifts are a continuation of trends over the five-year period so the extent of the impact of COVID-19 related shipping disruptions is unclear.[69]

There were no significant changes in shipping routes corresponding to the major ports of entry for container cargo from Northeast Asia in 2020 despite the shipping congestion that occurred that year. Los Angeles continued to be the major port of entry in 2020, receiving 36 percent of the volume (by kg) of container imports in 2020 (up from 35 percent in 2019), followed by Newark (part of the Port of New York and New Jersey) (11 percent, the same as in 2019), Long Beach (11 percent, up from 9 percent in 2019), and Savannah (10 percent, the same as in 2019). When congestion intensified during the course of the year, importers increased their reliance on Southern California ports. The combined share of container imports received by Los Angeles and Long Beach—two of the most congested ports—in December 2020 was higher than in December 2019.[70]

The COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on U.S. ports contributed to the corresponding disruptions in merchandise trade described here. While total volume of goods handled at ports in 2020 was similar to the volume in 2019, the year-on-year comparison obscures the V-shaped pattern (a sharp decrease followed by a sharp increase) in monthly changes in 2020. During the year, monthly volumes declined during the first half of the year and increased during the second half.[71] The number of 20-foot equivalent units (TEUs) handled per month declined 17.5 percent, from 3.7 million TEUs in January to 3.1 million in March 2020.[72] Monthly volumes remained at similar levels until June, when they began to rise. The number of containers handled increased 34 percent over the next four months, from 3.3 million TEUs in June to 4.4 million TEUs in October, and remained high through the end of the year.[73] The largest monthly volume increases occurred at the three largest ports—those of Los Angeles, Long Beach, and New York and New Jersey.[74]

The disruptions to the maritime shipping sector resulted in delayed merchandise shipments.[75] Furthermore, these delayed freight deliveries were more frequent and lasted longer in 2020 than in 2019.[76] The delays were a widespread problem, affecting not only the global supply chains of leading U.S. retailers and small businesses that import finished goods and intermediary parts, but also maritime freight, cargo handling facilities, and onshore transportation networks.[77] The more frequent and longer delays resulted in smaller inventories available to firms and slower deliveries to consumers.[78]

The shipping disruptions significantly affected the ability of firms to supply the U.S. market in a timely way. In the first half of the year, disruptions in air freight contributed to challenges in sourcing PPE and other COVID-19 related goods.[79] Many other sectors experienced significant challenges in the second half of the year due to the congestion at U.S. ports, particularly in Southern California (as discussed above). For example, the footwear and textiles and apparel sectors are heavily dependent on container imports through the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach.[80] Nike reported that “starting in late December container shortages and West Coast port congestion began to increase the transit times of inventory supply by more than three weeks. The result was a lack of available supply, delayed shipments to wholesale partners and lower-than-expected quarterly revenue growth.”[81] Similarly, Gap reported in its discussion of fourth quarter 2020 earnings that port congestion led to an increase in the volume of inventory in transit.[82] Impacts were not limited to these sectors, however, as many other sectors also import a significant volume in containers through these ports.[83]

The shipping disruptions and cost increases in the second half of 2020 likely had a disproportionate impact on small importers, according to industry representatives, although firms of all sizes were affected, as discussed in the Nike and Gap examples above.[84] Small firms were likely to be more severely impacted for several reasons. First, industry representatives indicate that shipping companies may prioritize freight for large customers that do a lot of business with their firms.[85] Second, smaller companies are less likely to have long-term contracts, and therefore may need to pay higher spot rates for shipping. Finally, large companies may be able to negotiate discounts due to the large volumes that they ship.[86]

By mid-2020, most maritime shipping capacity returned to 2019 levels. But port capacity, including container availability, continues to be strained and international air freight capacity has not yet returned to its pre-pandemic levels. Global merchandise trade continued to grow through the first quarter of 2021, as did U.S. merchandise trade.[87] As such, demand for transportation services still outstripped supply as of mid-2021.

For instance, the amount of time container ships spent waiting to be unloaded in mid-2021, particularly on the U.S. West Coast, was well above the pre-pandemic average.[88] To ease this trend, ocean carriers are ordering more ships and containers, however these will take several years to enter service.[89] Port backlogs are also predicted to last through at least 2022.[90] Early in the pandemic, some firms began to question their reliance on just-in-time delivery.[91] However, more recently, many leading firms largely have chosen to continue using the just-in-time model and prefer to make modifications to it, such as incorporating delays into supply-chain planning or near-shoring the production of certain inputs like key pharmaceutical ingredients.[92] The extent to which COVID-19 related transportation disruptions continue to ease and individuals and firms return to their former spending patterns and ways of doing business, will also affect future demand for merchandise trade and transportation services.

[1] This chapter primarily focuses on the effects of COVID-19 pandemic-related transportation disruptions on U.S. imports. However, the section on container shipping briefly discusses its effects on U.S. exports.

[2] About 90 percent of the volume of merchandise trade is transported by sea. OECD, “Ocean Shipping and Shipbuilding,” November 2019.

[3] U.S.-China trade disputes and the impending Brexit were among non-pandemic-related factors affecting global merchandise trade between 2019 and 2020. Trade Shifts reports usually examine trends in trade on an annual basis. However, given the significant changes in logistics during the course of 2020, this part of the report will break out certain trade data for half or a quarter of the year. UNCTAD, “Review of Maritime Transport 2020,” November 12, 2020. IHS Markit 2021, “United States Ports Export Statistics to the World,” monthly series through December 2020, accessed April 20, 2021.

[4] IHS Markit 2021, “United States Ports Export Statistics to the World,” monthly series through December 2020, accessed April 20, 2021.

[5] IHS Markit, Global Trade Atlas database, “United States Ports Import Statistics from-East Asia (Transport Modes: Vessel Container Only) Via Ports; All Ports, January 2016–December 2020,” accessed May 13, 2021. In the second half of 2020, the volume of U.S. maritime containerized imports from China increased year on year by 14.3 percent. In December 2020, China supplied nearly 60 percent of U.S. maritime containerized imports from East Asia. UNCTAD, “Review of Maritime Transport 2020,” November 12, 2020, 14.

[6] USDOC, BEA, Table 3.1: U.S. International Trade in Services, March 23, 2021. International Transactions, International Services, and International Investment Position Tables. U.S. exports of maritime freight services decreased by 1.8 percent between 2019 and 2020.

[7] A blank sailing refers to the cancellation of service for a scheduled route or the bypassing of a port on a scheduled route. According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), in 2019, the mainline East-West trade lane (which includes routes between Asia and Europe, the United States and Asia, and the United States and Europe) accounted for 39.1 percent of maritime containerized trade by volume.

[8] Paris, “Container Shipping Lines Cancel Sailings,” April 6, 2020. Shipping contracts dictate whether any penalties are assessed for canceling a sailing or a container slot on a vessel.

[9] Members of “THE” Alliance include the container shipping firms of Hapag-Lloyd (Germany), Ocean Network Express (Japan), and Yang Ming (Taiwan); the 2M Alliance includes Maersk Line (Denmark) and Mediterranean Shipping Company (MSC) (Switzerland); the Ocean Alliance includes Singapore-based CMA CGM Asia Shipping, including its subsidiary American President Lines (CMA CGM/APL), COSCO Shipping (China), and Evergreen Line (Taiwan). Knowler, “Alliances Outline Extensive Blank Sailings for Q3,” June 3, 2020. Overall, industry reports indicate that the alliances canceled about 15 to 30 percent of scheduled sailings on major maritime routes.

[10] Lademan, “Fewer Blank Sailings in Early 2021,” January 6, 2021. Estimates of the number of blank sailings during the first six months of 2020 vary between 990 and 1,476. See Miller, “How Canceled Sailings Will Impact US Ports,” May 4, 2020.

[11] Knowler, “Alliances Outline Extensive Blank Sailings for Q3,” June 3, 2020.

[12] Szakonyi, “Backlash Festers as Carriers’ Capacity Discipline Portends Profitable 2020,” July 8, 2020.

[13] Mongelluzzo, “US Imports from Asia Hit Record December Level,” January 19, 2021. The increase pertains to the volume of U.S. imports as measured in 20-foot equivalent units (TEUs), a standard measure of container capacity that corresponds to the dimension of a typical shipping container (which usually measures 20 feet long and 8 feet high).

[14] LaRocca, “Rising Maritime Freight Shipping Costs Impacted by Covid-19,” April 2021.

[15] Notteboom, Pallis, and Rodrigue, “Disruptions and Resilience in Global Container Shipping,” January 4, 2021, 184–86.

[16] Miller, “Maersk: Container Volumes Could Fall 25%,” May 13, 2020.

[17] Miller, “How Canceled Sailings Will Impact US Ports,” May 4, 2020.

[18] Notteboom, Pallis, and Rodrigue, “Disruptions and Resilience in Global Container Shipping,” January 4, 2021, 197–203.

[19] Bloomberg, “Shortage of New Shipping Containers,” March 16, 2021; Drewry, “Container Equipment Market Outlook Briefing (webinar),” April 27, 2021.

[20] Manufacturing capacity for shipping containers is primarily located in China. Bloomberg, “Shortage of New Shipping Containers Adds to Global Trade Turmoil,” March 16, 2021.

[21] UNCTAD Policy Brief, “Container Shipping in Times of COVID-19,” April 2021, 2.

[22] Turnaround times on routes from China to the United States and Europe increased from an average of 60 days before the pandemic to 100 days in December 2020. Qiu, Singh, and Khasawneh, “Boxed Out,” December 10, 2020; Drewry, “Container Equipment Market Outlook Briefing (webinar),” April 27, 2021.

[23] U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, "Impacts of Shipping Container Shortages," June 15, 2021.

[24] In part, ocean carriers did not want to delay ships’ departures (which is costly for carriers) to wait for containers to be repositioned and loaded with U.S. exports. Shipping rates per container also tend to be higher on routes from Asia to North America than on routes from North America to Asia. Leonard, “Why the Empty Container Math Doesn’t Add Up,” February 3, 2021; Freightos, “Freightos Baltic Container Freight Index,” accessed August 23, 2021.

[25] Large shipping lines such as Maersk often own the containers they use, while other shipping firms will lease containers from leasing companies. Lessors were estimated to own over half the container fleet in 2020. Direct ownership of containers is less expensive for firms, but leasing containers offers more flexibility. Production of shipping containers, concentrated in China, has been increasing but a decline in container orders for several years prior to COVID-19 had reduced manufacturing capacity. Drewry, “Container Equipment Market Outlook Briefing,” April 27, 2021; Dupin, “Lessors Own Growing Share,” April 30, 2018; Samuels, “Who Owns Shipping Containers,” October 15, 2019; U.S. House of Representatives Committee on House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, "Impacts of Shipping Container Shortages," June 15, 2021; Berger, “Where Did All the Shipping Containers Go?” August 4, 2021.

[26] In February 2021, the Port of Los Angeles reported that nearly 700 dockworkers were absent due to illness and 1,500 dockworkers had self-reported testing positive for COVID-19 in California. Loo, “COVID-19 Infecting Hundreds of Workers,” February 12, 2021; U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, hearing transcript, February 9, 2021 (testimony of Mario Cordero, Chairman of the Board of Directors for the American Association of Port Authorities), 4.

[27] Bradsher and Chokshi, “Virus Disrupts China’s Shipping,” February 27, 2020; Verma, “‘Very High Risk,’” December 12, 2020; Roosevelt, “COVID-19 Surge Could Shut Down Major California Ports,” January 20, 2021; Bloomberg, “One of World’s Top Ports Expects Delays,” May 29, 2021.

[28] Caminiti, “Lack of Workers,” September 28, 2021; Ziobro, “Shortage of Railroad Workers Threatens Recovery,” Jul 22, 2021.

[29] WHO, “WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks,” March 11, 2020.

[30] About 25 percent of seafarers globally come from the Philippines, with India, China, Indonesia, and Ukraine also contributing large numbers. Travel restrictions in these countries and flight cancellations also played a role in stranding seafarers. ILO, “Stranded Seafarers,” September 15, 2020; IMO, “400,000 Seafarers Stuck at Sea,” September 25, 2020.

[31] Chambers, “Chartered Flights See Crew Changes Take Off,” June 1, 2020.

[32] Hand, “Crew Costs to Rise 10–15% This Year Due to Covid-19,” September 15, 2020.

[33] Drewry, “COVID-19 Drives Up Ship Operating Costs,” accessed May 14, 2021.

[34] For a more detailed discussion on the impacts of a particular sector/industry, see the relevant sectoral sections in Part II of this report.

[35] CTKs are a standard industry measurement which multiplies the number of tons of revenue freight by the number of kilometers the freight travels.

[36] The CTK data series began in 1990. IATA, “Air Cargo Market Analysis,” December 2020.

[37] IATA, “Air Cargo Market Analysis,” December 2020.

[38] Since major routes to North America, Asia, and Europe represent a large portion of global cargo volumes, their decline accounted for most of the decrease in global cargo volumes in 2020, while their recovery accounted for much of the increase seen in 2021. IATA, “Air Cargo Market Analysis,” January 2021.

[39] USDOT, BTS, “Air Travel-Total-Seasonally Adjusted,” accessed July 2, 2021.

[40] IATA, “Air Cargo Market Analysis,” December 2020.

[41] The design of passenger planes, including different layouts and smaller cabin doors compared to dedicated freighters, gives them lower capacity as well as increased loading and unloading times. Passenger aircraft carrying cargo in the main cabin also require formal authorization from a national aviation authority (such as the Federal Aviation Administration in the United States). Morrison, “Passenger to Cargo Conversions Boom,” February 1, 2021; Freed, Rabinovitch, and Lampert, “Falling Plane Values,” December 13, 2020; Georgiadis, “Trade is Set to Remain Big Business for Airlines,” May 25, 2021; industry representative, interview by USITC, May 25, 2021; IATA, “Guidance for the Transport of Cargo,” May 4, 2020.

[42] Bushey, “Airlines Pivot to Cargo to Compensate for Loss of Passengers,” April 26, 2020.

[43] USDOT, BTS, “Air Travel-Total-Seasonally Adjusted,” accessed July 2, 2021; USDOT, BTS, “Air Travel-International-Seasonally Adjusted,” accessed July 2, 2021.

[44] Georgiadis, “Trade is Set to Remain Big Business for Airlines,” May 25, 2021.

[45] Karp, “The Coming Air Cargo Reality Check,” August 26, 2020; industry representative, interview by USITC, May 25, 2021.

[46] Brett, “Air Cargo Rates and Capacity on the Slide as PPE Demand Weakens,” June 16, 2020.

[47] For a more detailed discussion of the rise in demand for PPE in 2020, see the Textile and Apparel section of this report.

[48] There was a drop in the value of electronic products shipped via air freight from 2018 to 2019, while the value grew from 2019 to 2020. At the same time, the share of electronic products shipped via air freight increased from 2019 to 2020. Other factors that played a role in electronic trade shifts include supply chain disruptions, particularly in early 2020, and changes in consumer demand due to higher unemployment resulting from COVID-19. Drewry, “Container Equipment Market Outlook Briefing (webinar),” April 27, 2021; industry representative, interview by USITC staff, June 3, 2021; industry representative, interview by USITC, May 25, 2021; USITC DataWeb/Census, accessed August 19, 2021.

[49] Goodman et al., “‘I’ve Never Seen Anything Like This,’” March 6, 2021; LaRocca, “Rising Maritime Freight Shipping Costs Impacted by Covid-19,” April 2021.

[50] Knowler, “Alliances Outline Extensive Blank Sailings for Q3,” June 3, 2020.

[51] Bloomberg, “China Ends 2020 With Record Trade Surplus as Pandemic Goods Soar,” January 13, 2021; Hale, “Chinese Exports Grow 21% amid Global Appetite,” December 7, 2020; Leonard, “Why the Empty Container Math Doesn’t Add Up,” February 3, 2021.

[52] Freightos, “Freightos Baltic Container Freight Index,” accessed May 9, 2021.

[53] For example, some firms began holding larger inventories to mitigate supply chain disruptions. Steer and Wright, “Pandemic Triggers ‘Perfect Storm’ for Global Shipping Supply Chains,” December 10, 2020; Goodman and Chockshi, “How the World Ran out of Everything,” June 1, 2021.

[54] Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the cost to ship goods via air freight was about 12 times as expensive as sea freight, but by May 2021 that ratio dropped 50 percent. Knowler, “Air Cargo Cost Differential,” July 12, 2021.

[55] USDOL, Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Import/Export Price Indexes (MXP),” accessed June 14, 2021.

[56] Statista, “Impact of Coronavirus on Major Global Air Freight Rates,” May 2021.

[57] Industry representative, interview by USITC, May 25, 2021.

[58] Georgiadis, “Trade Is Set to Remain Big Business,” May 25, 2021; BIFA, “Air Freight Charter Prices Soar Towards Record Highs,” November 2020.

[59] Insurance and freight costs as reported by the U.S. Census Bureau are based on import charges data reported in official trade statistics. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, “The import charges represent the aggregate cost of all freight, insurance, and other charges (excluding U.S. import duties) incurred in bringing the merchandise from alongside the carrier at the port of exportation in the country of exportation and placing it alongside the carrier at the first port of entry in the United States.” The term “insurance and freight costs” will be used in this paragraph and the next rather than “import charges” for the ease of the reader. U.S. Census Bureau, “Guide to Foreign Trade Statistics,” accessed June 16, 2021.

[60] IHS Markit, “Global Trade Atlas Database,” accessed May 20, 2021; Ren, “Higher Shipping Costs,” April 12, 2021; Miller, “Battle of the Shipping Booms,” August 25, 2021.

[61] For more information on trade in these sectors, see the sections on textiles and apparel, minerals and metals, and chemicals and related products in Part II of this report.

[62] For more on PPE shipping challenges and price changes, see the textiles and apparel section in Part II and USITC, COVID-19 Related Goods, December 2020.

[63] This is a reversal of 2019, when large shipping cost increases took place in the first half of the year rather than in the second half.

[64] The changes in shipping rates from Northeast Asia in these sectors are related to several factors and vary by digest and product. For example, certain goods—such as certain cooking appliances included in minerals and metals—experienced increases in shipping costs likely due to the rise in container rates. For others—such as laboratory ware used in the COVID-19 response (a subset of chemicals and related products)—a large share of the cost increase was likely due to the urgent need to bring products in via air freight. Increases in shipping costs by sector are also driven by changes in product mixes. For example, one of the products driving the large increase in shipping costs in chemicals and related products was a change in the product mix to more vinyl tile. As discussed in the chemicals and related products section in Part II, this represented a surge in demand for vinyl tile, which has above-average transportation costs, rather than a large increase in shipping costs (which only rose by 2 percent for vinyl tile). Finally, while there were significant increases in shipping costs in these sectors on average, some digests show a decline in shipping costs. IHS Markit, “Global Trade Atlas Database,” accessed May 20, 2021; USITC DataWeb/Census, accessed May 19, 2021. For a more detailed description of the USITC digests, see footnote 38 above.

[65] These data are based on the landed duty-paid value of imports, whereas all other data in this section are based on general imports. USDOL, BLS, “Import/Export Price Indexes (MXP),” accessed May 28, 2021; USITC DataWeb/Census, accessed August 19, 2021.

[66] USITC DataWeb/Census, accessed July 1, 2021.

[67] Only limited anecdotal information is available that explains the extent to which these cost increases were passed along to consumers in 2020. Some firms indicated that they passed along cost increases, while others said that they did not do so. In 2021, however, it appears that some of these costs are being passed on to customers. According to a National Retail Federation survey of its members, “all respondents said their costs have increased with a majority (75%) having had to pass along some of the costs to consumers.” USITC DataWeb/Census, accessed July 1, 2021; Ren, “Higher Shipping Costs,” April 12, 2021; NRF, “Letter to President Joseph R. Biden,” June 14, 2021.

[68] For more discussion on the change in shipping methods for COVID-19 related goods, see USITC, COVID-19 Related Goods, December 2020.

[69] USITC/Census, “DataWeb,” accessed August 19, 2021.

[70] IHS Markit, “Global Trade Atlas Database,” accessed May 20, 2021.

[71] The annual total number of containers handled by the 10 largest U.S. container ports declined 0.5 percent from 45 million TEUs in 2019 to 44.8 million TEUs in 2020. USDOT, BTS, “Port Performance Freight Statistics Program,” accessed May 31, 2021.

[72] A TEU is a standard measurement of container shipping, corresponding to the dimensions of a standard shipping container (which typically measures 20 feet long and 8 feet high). In 2019, U.S. ports handled on average 3.7 million TEU per month. BTS, “Port Performance Freight Statistics Program,” accessed May 31, 2021.

[73] USDOT, BTS, “Port Performance Freight Statistics Program,” accessed May 31, 2021.

[74] USDOT, BTS, “Port Performance Freight Statistics Program,” accessed May 31, 2021.

[75] Steer and Wright, “Pandemic Triggers ‘Perfect Storm’,” December 10, 2020; Goodman et al., “‘I’ve Never Seen Anything Like This,’” March 6, 2021.

[76] Miller, “Container Ships Suffer Record Delays as Demand Spikes,” December 17, 2020.

[77] Notteboom, Pallis, and Rodrigue, “Disruptions and Resilience in Global Container Shipping and Ports,” January 4, 2021, 193–97; Arcieri, “Retailers to Face Continued Pandemic-Induced Supply Chain Pain,” January 28, 2021.

[78] Link-Wills, “Hapag-Lloyd CEO,” February 19, 2021; Miller, “Container Ships Suffer Record Delays as Demand Spikes,” December 17, 2020.

[79] For more on shipping challenges and the sourcing of COVID-19 related goods, see: USITC, COVID-19 Related Goods, December 2020.

[80] IHS Markit, “Global Trade Atlas Database,” accessed May 20, 2021.

[81] Other footwear suppliers and retailers, such as Skechers and Foot Locker, also reported challenges due to shipping delays and port congestion. See also the discussion in the footwear section in Part II. Motley Fool, “Nike Inc (NKE) Q3 2021 Earnings Call Transcript,” March 18, 2021; Motley Fool, “Skechers USA Inc (SKX) Q4 2020 Earnings Call Transcript,” February 4, 2021; Motley Fool, “Foot Locker Inc (FL) Q4 2020 Earnings Call Transcript,” February 26, 2021.

[82] Motley Fool, “Gap (GPS) Q4 2020 Earnings Call Transcript,” March 4, 2021.

[83] IHS Markit, “Global Trade Atlas Database,” accessed May 20, 2021.

[84] Motley Fool, “Nike Inc (NKE) Q3 2021 Earnings Call Transcript,” March 18, 2021; Motley Fool, “Skechers USA Inc (SKX) Q4 2020 Earnings Call Transcript,” February 4, 2021; Motley Fool, “Foot Locker Inc (FL) Q4 2020 Earnings Call Transcript,” February 26, 2021; Motley Fool, “Gap (GPS) Q4 2020 Earnings Call Transcript,” March 4, 2021.

[85] Bloomberg, “Why Tracy Can’t Ship,” accessed June 30, 2021; Steer, Eley, and Romei, “European Retailers Face Goods Shortages as Shipping Costs Soar,” January 31, 2021.

[86] Ren, “Higher Shipping Costs,” April 12, 2021; Bloomberg, “Why Tracy Can’t Ship,” accessed June 30, 2021; industry representative, interview by USITC staff, June 30, 2021.

[87] WTO, “First Quarter 2021 Merchandise Trade,” June 24, 2021; USDOC, BEA, “U.S. International Trade in Goods and Services,” June 2021,” August 5, 2021.

[88] Rosalsky, “How ‘Chaos’ in The Shipping Industry is Choking the Economy,” June 15, 2021.

[89] A typical container ship takes three years to build, while container production has not been able to ramp up to stay level with demand. Chokshi, “How Giant Ships Are Built,” June 17, 2020; Georgiadis, “Trade Is Set to Remain Big Business,” May 25, 2021; Paris, “Ship Orders Surge,” June 8, 2021; Xie, Paris, and Yang, “Fresh Covid-19 Outbreaks in Asia,” June 11, 2021; Miller, “No Relief,” April 30, 2021; Rivero, "A Shipping Container Shortage," June 30, 2021.

[90] Miller, “No Relief,” April 30, 2021.

[91] Hadwick, “The End of Just-in-Time?” July 3, 2020.

[92] Leonard, “Supply Chains Stick with Lean Methods,” June 1, 2021; Barbella, “Pandemic Has Accelerated Nearshoring Medtech Materials,” August 6, 2021.

Bibliography

Arcieri, Katie. “Retailers to Face Continued Pandemic-Induced Supply Chain Pain Well into 2021.” S&P Global Platts, January 28, 2021. https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/latest-news-headlines/retailers-to-face-continued-pandemic-induced-supply-chain-pain-well-into-2021-61981889.

Barbella, Michael. “Pandemic Has Accelerated Nearshoring Medtech Materials,” August 6, 2021. https://www.mpo-mag.com/contents/view_online-exclusives/2021-08-06/pandemic-has-accelerated-nearshoring-medtech-materials/.

Berger, Paul. “Where Did All the Shipping Containers Go?” The Wall Street Journal, August 4, 2021. https://www.wsj.com/articles/where-did-all-the-shipping-containers-go-11628104583.

Bloomberg. “China Ends 2020 with Record Trade Surplus as Pandemic Goods Soar,” January 13, 2021. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-01-14/china-s-trade-surplus-hits-record-as-pandemic-fuels-exports.

Bloomberg. “One of World’s Top Ports Expects Delays on China Covid Outbreak,” May 29, 2021. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-05-29/china-s-yantian-port-extends-container-limits-to-curtail-covid.

Bloomberg. “Shortage of New Shipping Containers Adds to Global Trade Turmoil,” March 16, 2021. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-03-16/shortage-of-new-shipping-containers-adds-to-global-trade-turmoil.

Bloomberg. “Why Tracy Can’t Ship a Teddy Bear from Hong Kong Right Now,” June 15, 2021. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-06-15/transcript-what-a-teddy-bear-can-tell-us-about-the-global-shipping-crisis.

Bradsher, Keith, and Niraj Chokshi. “Virus Disrupts China’s Shipping, and World Ports Feel the Impact.” The New York Times, February 27, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/27/business/economy/china-coronavirus-shipping-ports.html.

Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). See U.S. Department of Labor (USDOL). Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

Bushey, Claire. “Airlines Pivot to Cargo to Compensate for Loss of Passengers.” Financial Times, April 26, 2020. https://www.ft.com/content/c84351be-bf98-4831-9e7f-428f9c01f06b.

Caminiti, Susan. “Lack of Workers Is Further Fueling Supply Chain Woes.” CNBC, September 28, 2021. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/09/28/companies-need-more-workers-to-help-resolve-supply-chain-problems.html.

Census. See U.S. Census Bureau.

Chambers, Sam. “Chartered Flights See Crew Changes Take Off.” Splash247, June 1, 2020. https://splash247.com/chartered-flights-see-crew-changes-take-off/.

Chaney Cambon, Sarah. “Retail Sales Dropped 1.3% in May as Pandemic Shopping Habits Shifted.” The Wall Street Journal, June 15, 2021. https://www.wsj.com/articles/us-economy-may-2021-retail-sales-11623701250.

Chokshi, Niraj. “How Giant Ships Are Built.” The New York Times, June 17, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/06/17/business/economy/how-container-ships-are-built.html.

CPC Consultants. “Port Congestion Improving, but Post Pandemic Pricing Pressure Expected to Continue into Q3 & Q4.” CPC Consultants, May 25, 2021. https://www.cpc-consultants.net/blog/2021-ocean-shipping-outlook.

Drewry. “COVID-19 Drives up Ship Operating Costs,” November 30, 2020. https://www.drewry.co.uk/news/news/covid-19-drives-up-ship-operating-costs.

Dupin, Chris. “Lessors Own Growing Share of Container Fleet.” FreightWaves, April 30, 2018. https://www.freightwaves.com/news/lessors-own-growing-share-of-container-fleet.

FourKites. “Live Network Congestion Times.” Accessed May 24, 2021. https://live.fourkites.com/port-congestion.

Freightos. “Freightos Baltic Container Freight Index.” Accessed various dates. https://fbx.freightos.com.

Georgiadis, Philip. “Trade Is Set to Remain Big Business for Airlines.” Financial Times, May 25, 2021. https://www.ft.com/content/8a437020-cbde-4244-bcae-60f64f0016e2.

Goodman, Peter S., Alexandra Stevenson, Niraj Chokshi, and Michael Corkery. “‘I’ve Never Seen Anything Like This’: Chaos Strikes Global Shipping.” The New York Times, March 6, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/06/business/global-shipping.html.

Goodman, Peters S and Chokshi, Niraj. “How the World Ran Out of Everything.” The New York Times, June 1, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/01/business/coronavirus-global-shortages.html.

Hadwick, Alex. “The End of Just-in-Time?” Reuters Events, July 3, 2020. https://www.reutersevents.com/supplychain/supply-chain/end-just-time.

Hale, Thomas. “Chinese Exports Grow 21% Amid Global Appetite for Pandemic Products.” Financial Times, December 7, 2020. https://www.ft.com/content/99d9fea1-db30-4dd3-a41a-7245a2eb090a.

Hand, Marcus. “Crew Costs to Rise 10–15% This Year Due to Covid-19: Drewry.” Seatrade Maritime, September 15, 2020. https://www.seatrade-maritime.com/ship-operations/crew-costs-rise-10-15-year-due-covid-19-drewry.

International Air Transport Association (IATA). “Air Cargo Market Analysis,” January 2021. https://www.iata.org/en/iata-repository/publications/economic-reports/air-freight-monthly-analysis---january-2021/.

International Air Transport Association (IATA). “Air Cargo Market Analysis,” December 2020. https://www.iata.org/en/iata-repository/publications/economic-reports/air-freight-monthly-analysis---december-2020/.

International Air Transport Association (IATA). “Guidance for the Transport of Cargo and Mail on Aircraft Configured for the Carriage of Passengers,” May 4, 2020. https://www.iata.org/contentassets/094560b4bd9844fda520e9058a0fbe2e/guidance-safe-transportation-cargo-passenger-cabin.pdf.

IHS Markit. “Global Trade Atlas Database.” Accessed various dates. https://connect.ihsmarkit.com.

International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO). “Air Transport Monthly Monitor,” February 2021. https://www.icao.int/sustainability/Documents/MonthlyMonitor-2021/Monthly_Monitor_February_2021.pdf.

International Labour Organization (ILO). “Stranded Seafarers: A ‘Humanitarian Crisis,” September 15, 2020. http://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_755390/lang--en/index.htm.

International Maritime Organization (IMO). “400,000 Seafarers Stuck at Sea as Crew Change Crisis Deepens,” September 25, 2020. https://imo.org/en/MediaCentre/PressBriefings/Pages/32-crew-change-UNGA.aspx.

Journal of Commerce. “COVID-19: Pile up of Non-Essential Cargo at US Ports Raises Alarms,” March 27, 2021. https://www.joc.com/port-news/us-ports/north-carolina-ports-authority/east-coast-ports-add-storage-non-essential-shipments-pile_20200327.html.

Knowler, Greg. “Alliances Outline Extensive Blank Sailings for Q3.” Journal of Commerce, June 3, 2020. https://www.joc.com/maritime-news/alliances-outline-extensive-blank-sailings-q3_20200603.html.

Lademan, David. “Fewer Blank Sailings in Early 2021 on Year amid Strong Containerized Trade Demand: EeSea.” S&P Global Platts, January 6, 2021. https://www.spglobal.com/platts/en/market-insights/latest-news/shipping/010621-fewer-blank-sailings-in-early-2021-on-year-amid-strong-containerized-trade-demand-eesea.

LaRocca, Gregory. “Rising Maritime Freight Shipping Costs Impacted by Covid-19.” U.S. International Trade Commission (USITC) Executive Briefing on Trade, April 2021. https://www.usitc.gov/publications/332/executive_briefings/ebot_greg_larocca_freight_costs_weighing_covid_pdf.pdf.

Leonard, Matt. “Supply Chains Stick with Lean Methods despite Inventory Woes.” Supply Chain Dive, June 1, 2021. https://www.supplychaindive.com/news/inventory-sales-ratio-March-pandemic-retail-supply-chain-planning/601064/.

Leonard, Matt. “Why the Empty Container Math Doesn’t Add up in US Exporters’ Favor.” Supply Chain Dive, February 3, 2021. https://www.supplychaindive.com/news/empty-container-ports-ocean-supply-chain-explained/593493/.

Link-Wills, Kim. “Hapag-Lloyd CEO: COVID, Congestion, Container Shortage Form ‘Perfect Storm.’” FreightWaves, February 19, 2021. https://www.freightwaves.com/news/hapag-lloyd-ceo:-covid-congestion-container-shortage-form-perfect-storm.

Loo, Nancy. “COVID-19 Infecting Hundreds of Workers Leads to Cargo Ship Traffic Jam.” ABC 27 News, February 12, 2021. https://www.abc27.com/news/covid-19-infecting-hundreds-of-workers-leads-to-cargo-ship-traffic-jam/.

McLain, Sean. “Auto Makers Retreat from 50 Years of ‘Just in Time’ Manufacturing.” The Wall Street Journal, May 3, 2021. https://www.wsj.com/articles/auto-makers-retreat-from-50-years-of-just-in-time-manufacturing-11620051251.

Miller, Greg. “Battle of the Shipping Booms: Containers ’21 vs Dry Bulk ’07-’08.” FreightWaves, August 25, 2021. https://www.freightwaves.com/news/which-boom-is-bigger-containers-today-or-dry-bulk-07-08.

Miller, Greg. “Container Ships Suffer Record Delays as Demand Spikes.” FreightWaves, December 17, 2020. https://www.freightwaves.com/news/container-ships-suffer-record-delays-as-demand-spikes.

Miller, Greg. “How Canceled Sailings Will Impact US Ports—and When.” FreightWaves, May 4, 2020. https://www.freightwaves.com/news/how-canceled-sailings-will-impact-us-ports-and-when.

Miller, Greg. “Maersk: Container Volumes Could Fall 25%.” FreightWaves, May 13, 2020. https://www.freightwaves.com/news/maersk-container-volumes-could-fall-25.

Miller, Greg. “No Relief: Global Container Shortage Likely to Last until 2022.” FreightWaves, April 30, 2021. https://www.freightwaves.com/news/no-relief-global-container-shortage-likely-to-last-until-2022.

Mongelluzzo, Bill. “LA-LB Container Dwells Edge toward Normalcy.” Journal of Commerce, April 24, 2019. https://www.joc.com/port-news/us-ports/port-los-angeles/la-lb-container-dwells-edge-toward-normalcy_20190424.html.

Mongelluzzo, Bill. “US Imports from Asia Hit Record December Level.” Journal of Commerce, January 19, 2021. https://www.joc.com/maritime-news/container-lines/us-imports-asia-hit-record-december-level_20210119.html.

Morrison, Murdo. “Passenger to Cargo Conversions Boom, but Can It Last?” FlightGlobal.com, February 1, 2021. https://www.flightglobal.com/flight-international/passenger-to-cargo-conversions-boom-but-can-it-last/142047.article.

Motley Fool. “Nike Inc (NKE) Q3 2021 Earnings Call Transcript,” March 18, 2021. https://www.fool.com/earnings/call-transcripts/2021/03/19/nike-inc-nke-q3-2021-earnings-call-transcript/.

Motley Fool. “Foot Locker Inc (FL) Q4 2020 Earnings Call Transcript,” February 26, 2021. https://www.fool.com/earnings/call-transcripts/2021/02/26/foot-locker-inc-fl-q4-2020-earnings-call-transcrip/.

Motley Fool. “Gap (GPS) Q4 2020 Earnings Call Transcript,” March 4, 2021. https://www.fool.com/earnings/call-transcripts/2021/03/05/gap-gps-q4-2020-earnings-call-transcript/.

Motley Fool. “Skechers USA Inc (SKX) Q4 2020 Earnings Call Transcript,” February 4, 2021. https://www.fool.com/earnings/call-transcripts/2021/02/05/skechers-usa-inc-skx-q4-2020-earnings-call-transcr/.

National Retail Federation (NRF). “Letter to President Joseph R. Biden,” June 14, 2021. http://d22f3d5c92fe72fd8ca1-d54e62f2f7fc3e2ff1881e7f0cef284e.r22.cf1.rackcdn.com/Memo%20Attachments/President%20Biden%20NRF%20Port%20Congestion%20Meeting%20Request%20Letter%20-%20Updated%20Final%20061421.pdf.

Notteboom, Theo, Thanos Pallis, and Jean-Paul Rodrigue. “Disruptions and Resilience in Global Container Shipping and Ports: The COVID-19 Pandemic versus the 2008–2009 Financial Crisis.” Maritime Economics & Logistics 23, no. 2 (January 4, 2021): 179–210. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41278-020-00180-5.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). “Ocean Shipping and Shipbuilding,” November 2019. https://www.oecd.org/ocean/topics/ocean-shipping/.

Paris, Costas. “Container Shipping Lines Cancel Sailings to Weather Coronavirus Storm.” The Wall Street Journal, April 6, 2020. https://www.wsj.com/articles/container-shipping-lines-cancel-sailings-to-weather-coronavirus-storm-11586205167.

Paris, Costas. “Ship Orders Surge as Carriers Rush to Add Capacity.” The Wall Street Journal, June 8, 2021. https://www.wsj.com/articles/ship-orders-surge-as-carriers-rush-to-add-capacity-11623179052.

Port of Los Angeles. “Seroka to ILWU: ‘Thank You,’” May 11, 2021. https://www.portoflosangeles.org/references/2021-news-releases/news_051121_thankyouilwu.

Qiu, Stella, Shivani Singh, and Rsolan Khasawneh. “Boxed Out: China’s Exports Pinched by Global Run on Shipping Containers.” Reuters, December 10, 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-global-shipping-container-idUSKBN28K0UA.

Ren, Henry. “Higher Shipping Costs Are Here to Stay, Sparking Price Increases.” Bloomberg, April 12, 2021. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-04-12/higher-shipping-costs-are-here-to-stay-sparking-price-increases.

Ronan, Dan. “Ports Say Business Beginning to Recover.” Transport Topics, August 26, 2020. https://www.ttnews.com/articles/ports-say-business-beginning-recover.

Roosevelt, Margot. “COVID-19 Surge Could Shut Down Major California Ports.” Los Angeles Times, January 20, 2021. https://www.latimes.com/business/story/2021-01-20/covid-surge-hits-la-ports-increasing-need-for-vaccines.

Rosalsky, Greg. “How ‘Chaos’ in The Shipping Industry is Choking the Economy.” NPR, June 15, 2021. https://www.npr.org/sections/money/2021/06/15/1006381735/how-chaos-in-the-shipping-industry-is-choking-the-economy.

Schwerdtfeger, Max. “Chinese Exports to Accelerate Global Port Recovery.” Port Technology International, September 16, 2020. https://www.porttechnology.org/news/chinese-exports-to-accelerate-global-port-recovery/.

Steer, George, Jonathan Eley, and Valentina Romei. “European Retailers Face Goods Shortages as Shipping Costs Soar.” Financial Times, January 31, 2021. https://www.ft.com/content/40d23da5-c321-4b56-8ec7-551573a7a485.

Steer, George, and Robert Wright. “Pandemic Triggers ‘Perfect Storm’ for Global Shipping Supply Chains.” Financial Times, December 10, 2020. https://www.ft.com/content/eb21056b-5773-422a-ab78-92e59cddc1b5.

Szakonyi, Mark. "Backlash Festers as Carriers' Capacity Discipline Portends Profitable 2020." Journal of Commerce, July 8, 2020. https://www.joc.com/maritime-news/container-lines/possible-profitable-2020-container-shipping-draws-backlash_20200708.html.

Tirschwell, Peter. “Slower Container Circulation Cripples Global Shipping System.” Journal of Commerce, February 18, 2021. https://www.joc.com/maritime-news/container-lines/slower-container-circulation-cripples-global-shipping-system_20210218.html.

Tirschwell, Peter. “US Port Congestion Solutions Bump into Third Rail of Labor.” Journal of Commerce, April 13, 2021. https://www.joc.com/port-news/port-productivity/us-port-congestion-solutions-bump-third-rail-labor_20210413.html.

United Nations Center for Trade and Development (UNCTAD). “Review of Maritime Transport 2020,” November 12, 2020. https://unctad.org/webflyer/review-maritime-transport-2020.

U.S. Department of Labor (USDOL). Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). “Import/Export Price Indexes (MXP).” Accessed May 28, 2021. https://www.bls.gov/mxp/.

U.S. Census Bureau. “Guide to Foreign Trade Statistics.” Accessed June 16, 2021. https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/guide/sec2.html#imp_charges.

U.S. Department of Labor (USDOL). Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). “Import/Export Price Indexes (MXP).” Accessed June 14, 2021. https://www.bls.gov/mxp/.

U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT). Bureau of Transportation Statistics (BTS). “Port Performance Freight Statistics Program.” Accessed May 31, 2021. https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/gsearch?collection=dot:35533&type1=mods.title&fedora_terms1=Port+Performance+Freight+Statistics.

U.S. House of Representatives. Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure. “Impacts of Shipping Container Shortages, Delays, and Increased Demand on the North American Supply Chain.” June 15, 2021. Video, 2:32:00. 2:06:00, June 15, 2021. https://transportation.house.gov/committee-activity/hearings/impacts-of-shipping-container-shortages-delays-and-increased-demand-on-the-north-american-supply-chain.

U.S. International Trade Commission (USITC). COVID-19 Related Goods: The U.S. Industry, Market, Trade, and Supply Chain Challenges. USITC Publication 5145, December 2020. https://www.usitc.gov/publications/332/pub5145.pdf.

U.S. International Trade Commission. Interactive Tariff and Trade DataWeb (USITC DataWeb)/U.S. Census Bureau (Census). Accessed various dates. http://dataweb.usitc.gov.

Verma, Pranshu. “‘Very High Risk’: Longshoremen Want Protection from the Virus So They Can Stay on the Job.” The New York Times, December 12, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/12/us/politics/coronavirus-longshoremen-ports.html.

World Health Organization (WHO). “WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19—11 March 2020,” March 11, 2020. https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020.

Xie, Stella Yifan, Costas Paris, and Stephanie Yang. “Fresh Covid-19 Outbreaks in Asia Disrupt Global Shipping, Chip Supply Chain.” The Wall Street Journal, June 11, 2021. https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-global-logistics-logjam-shifts-to-shenzhen-from-suez-11623403801.

Ziobro, Paul. “Shortage of Railroad Workers Threatens Recovery.” The Wall Street Journal, July 22, 2021. https://www.wsj.com/articles/shortage-of-railroad-workers-threatens-recovery-11626953584.