ECONOMICS WORKING PAPER SERIES

ANALYSIS OF EMPLOYMENT CHANGES OVER TIME

IN THE U.S. MOTOR VEHICLE INDUSTRY

David

Coffin

Tamar Khachaturian

David Riker

Working Paper 2016-08-A

U.S. INTERNATIONAL TRADE COMMISSION

500 E Street SW

Washington, DC 20436

August 2016

Special thanks to Martha Lawless, Deborah McNay, James Stamps, and Ravinder Ubee for comments and assistance with this working paper.

Office

of Economics working papers are the result of ongoing professional research of

USITC Staff and are solely meant to represent the opinions and professional

research of individual authors. These papers are not meant to represent in any

way the views of the U.S. International Trade Commission or any of its

individual Commissioners. Working papers are circulated to promote the active

exchange of ideas between USITC Staff and recognized experts outside the USITC

and to promote professional development of Office Staff by encouraging outside

professional critique of staff research.

Analysis of Employment Changes over Time in the U.S. Motor Vehicle Industry

David Coffin, Tamar Khachaturian, and David Riker

Office of Economics Working Paper 2016-08-A

August 2016

ABSTRACT

Over the period from 1997 to 2014, U.S. employment in the combined motor vehicle industry declined from 932,265 to 719,983 employees. During this time, significant changes in trade and non-trade factors occurred that have likely impacted employment, such as the value and composition of U.S. imports and exports and the intensified use of technology in manufacturing which increased labor productivity in some segments of the industry. This analysis decomposes the annual growth rates of employment in three separate segments of the combined motor vehicle industry into the contributions from international trade, labor productivity, and total U.S. consumption. Employment fell in both the motor vehicle and the parts manufacturing segments during this period. Labor productivity gains and increased imports both contributed to the employment declines, with labor productivity associated with a larger decline in employment. In both segments, higher domestic consumption played a larger role than increased exports in offsetting part of the employment declines. On the other hand, the vehicle body manufacturing segment posted an employment increase during this period. In this segment, employment gains from increased domestic consumption and exports offset the reductions in employment from gains in labor productivity.

David Coffin

Office of Industries, Advanced Technology and Machinery Division

Tamar Khachaturian

Office of Industries, Services Division

David Riker

Office of Economics, Research Division

Introduction

The

expansion in international trade in motor vehicles has coincided with

persistent declines in U.S. employment in the combined industry. Between 1997

and 2014, total U.S. imports of motor vehicles, bodies, and parts increased a

cumulative 128.3 percent ($169 billion), and U.S. exports increased a

cumulative 111.0 percent ($69 billion).[1]

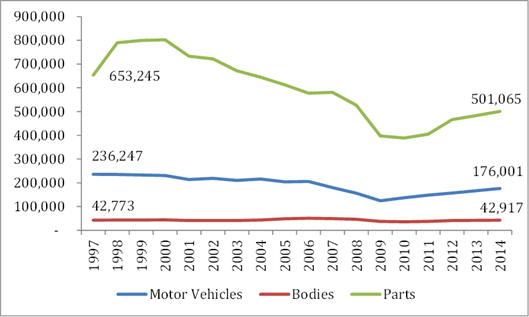

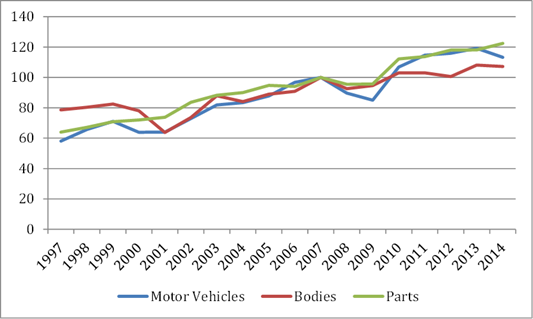

During the same time, employment declined a cumulative 22.8 percent, from 932,265

to 719,983 employees (figure 1).

Figure 1. U.S. employment: motor vehicles, parts, and bodies (19972014)

Source: U.S. Census, ASM (accessed July 1, 2016). Corresponds to table A.1 in the appendix.

While

part of the change in industry employment is likely tied to the growth of

international trade, it also reflects improvements in labor productivity in the

industry and in total consumption of motor vehicles in the U.S. market. This

research note uses a growth accounting framework to

quantify the relative contributions of changes in trade, technology, and total

consumption in some cases positive, in others negative to the historical declines in industry

employment. An increase in consumption in the United States due to an increase

in aggregate demand increases labor demand and therefore employment in the U.S.

industry. Likewise, an increase in U.S. exports due to an increase in foreign

demand increases employment in the U.S. industry. On the other hand, an

increase in imports due to a reduction in foreign costs of production generally

reduces employment in the U.S. industry. Finally, an increase in labor

productivity in the United States could increase or reduce employment in the

U.S. industry depending on the price sensitivity of the demand for the product.

Segments of the U.S. Motor Vehicle Industry

The

manufacture of U.S. motor vehicles in the United States is reported in NAICS

codes 3361, 336211, and 3363.[2]

NAICS code 3361 (motor vehicle manufacturing) encompasses the manufacturing of

passenger vehicles, heavy trucks, and buses. NAICS code 336211 covers the

manufacturing of vehicle bodies. NAICS code 3363 (motor vehicle parts

manufacturing) covers manufacturing of major motor vehicle systems, but may not

include all of the indirect inputs such as steel. Table 1 reports the relative

size of these three distinct segments and their engagement in international

trade.

Table 1. Statistics for the U.S. Motor Vehicle Industry, by Segment in 2014

|

|

NAICS 3361 Motor Vehicle Manufacturing |

NAICS 336211 Motor Vehicle Body Manufacturing |

NAICS 3363 |

|

Industry Employment (thousand) |

176,001 |

42,917 |

501,065 |

|

Total Value of Shipments (million dollars) |

307,269 |

13,225 |

244,688 |

|

Exports (million dollars) |

72,797 |

452 |

53,180 |

|

Imports (million dollars) |

190,764 |

784 |

106,487 |

Source: U.S. Census, ASM (accessed July 1, 2016); USITC DataWeb/USDOC (accessed July 1, 2016).

The data on the annual value of shipments and employment of the U.S. producers are from the Annual Survey of Manufactures and the Economic Census for 1997 through 2014. The data on the annual value of U.S. imports and exports are from the USITC’s Trade Dataweb. They are the landed duty-paid value of U.S. imports for consumption and the free alongside ship value of U.S. domestic exports of these industries from 1997 to 2014.

Evolution of the U.S. Motor Vehicle Industry

This section provides a short discussion of trends in each of the components of the employment analysis: imports, exports, labor productivity, and domestic consumption. Then the following section quantifies the contribution of these trends to changes in industry employment.

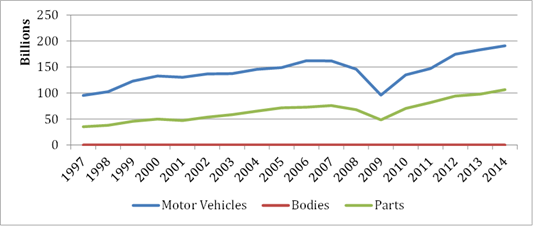

Imports

U.S. imports of vehicles, parts, and bodies all increased significantly during the 19972014 period. On a percentage basis U.S. parts imports increased the most (202 percent) to over $106 billion, while the $95 billion increase in the absolute value of vehicle imports to nearly $191 billion in 2014 was greater than the other two NAICS codes (figure 2). U.S. imports of bodies are relatively insignificant because bodies are typically produced at the assembly plant by the vehicle manufacturer and are thus unlikely to cross borders.[3]

Figure 2. U.S. imports of motor vehicles, parts, and bodies (19972014)

Source: USITC Dataweb (accessed July 12, 2016). Imports for consumption used. Corresponds to table A.2 in the appendix.

The

four largest sources for U.S. imports of motor vehicles, parts, and bodies in

2014 were Mexico, Canada, China, and Japan. Canada and Mexico, along with the

United States, are part of North America’s integrated motor vehicle supply

chain, with vehicles and parts traded freely between the three countries.[4]

Mexico has become the leading supplier of parts and vehicles to the United

States, rising from third largest in 1997. China is currently the third largest

source of vehicle parts to the United States, supplying over $12 billion in

2014, compared to $300 million in 1997.[5]

Japan is also a significant supplier of vehicles and parts to the United

States. However, Japanese companies have invested heavily in Mexico and Canada

in recent years, which have likely redirected supply to the United States to

come from those countries rather than directly from Japan.[6]

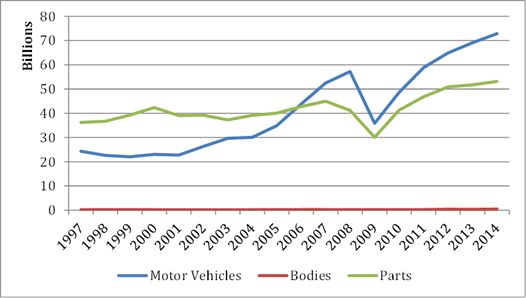

Exports

U.S. exports of motor vehicles, parts, and bodies have increased significantly, from less than $61 billion in 1997 to more than $126 billion in 2014. U.S. exports of motor vehicles increased the most, growing from $24 billion in 1997 to $73 billion in 2014 (figure 3).

Figure 3. U.S. exports of motor vehicles, parts, and bodies (19972014)

Source: USITC Dataweb (accessed July 12, 2016). Domestic exports used. Corresponds to table A.3 in the appendix.

The four largest destinations for exports of products of vehicles, parts, and bodies in 2014 were Canada, Mexico, China, and Germany. Due to the integration of the North American supply chain discussed above, Canada and Mexico are also top destinations for U.S. exports. Canada is the leading U.S. market for these exports of all three categories, whereas Mexico is one of the top four destinations for all three categories. China, the world’s largest single-country vehicle market, is a major destination for U.S. vehicles and part exports, ranking as the second largest market for U.S. motor vehicle exports, and third largest for motor vehicle parts exports. Germany is the third largest U.S. market for motor vehicle exports, but U.S. exports of motor vehicle bodies and parts to Germany total less than $1 billion.

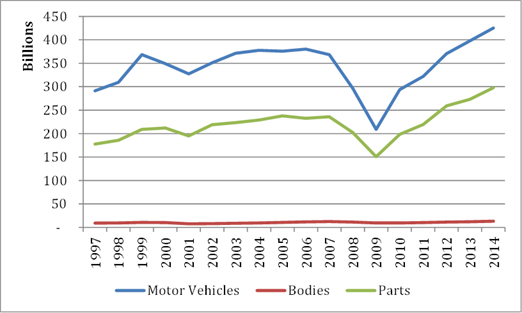

Consumption

Consumption of goods in this industry is primarily driven by macroeconomic trends. When the economy is growing, consumers purchase vehicles. When consumers purchase vehicles, manufacturers purchase parts. When consumers stop purchasing vehicles, manufacturers stop purchasing parts, as occurred during the economic downturn (figure 4).

Figure 4. U.S. consumption: motor vehicles, parts, and bodies (19972014)

Source: U.S. Census, ASM and U.S. International Trade Commission Dataweb (accessed July 1, 2016). Note: Total consumption is measured as total shipments of the U.S. industry minus U.S. exports plus U.S. imports. Corresponds to table A.4 in the appendix.

Productivity

During the 19972014 period, labor productivity in all three industry segments increased (figure 5). Several factors have likely contributed to these improvements in productivity. First, there has been a rise in the use of technologyincluding robotics, automation, and digital technologies in the production of vehicles and parts. The motor vehicle industry is the top purchaser of industrial robots, and installations of industrial robots increased significantly between 2010 and 2014.[7] Further, many vehicle manufacturers upgraded assembly plants to be more flexible, allowing different vehicle models to be produced on the same assembly line.[8] This flexibility reduces the need for different plants for each specific model and helps manufacturers to redistribute assembly based on demand. Also, upgraded plants operating at higher production capacities were likely one of the factors in increased productivity. Finally, the closure of older plants reduced overall production capacity, but likely contributed to capacity utilization rising to 77 percent for all motor vehicle and parts manufacturing in 2014, a level not seen since the first quarter of 2005.[9] Productivity in the remaining plants was likely higher than those that were closed during the economic downturn.

Figure 5. U.S. labor productivity: motor vehicles, parts, and bodies (19972014)

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Labor Productivity and Costs Database. Corresponds to table A.5 in the appendix.

Framework for Analyzing the Changes in Industry Employment

We

model the average annual percent changes in industry employment as a

combination of the percent changes in several components (1) labor productivity, (2) total U.S.

consumption of the products of the industry, (3) U.S. exports of the products

of the industry, and (4) the U.S. imports of these products based on a mathematical accounting

relationship between the industry variables. The model quantifies the

contributions of the components to the whole, based on the growth rates of the

components and their initial size relative to total industry shipments.

Equation (1) defines the value

of output per worker in segment in year :

(1)

is labor productivity, defined as physical output per worker, and is the price of the product. The numerator on the right-hand side of equation (1), U.S. exports plus total U.S. consumption minus U.S. imports , is equal to total shipments of the segment. is employment in the segment. Equation (1) implicitly defines the price index as a function of the other variables.

Equation (2) is an expression

for employment in segment based on equation (1).

(2)

Equation (3) relates the percent changes

in industry employment to the percent changes in the price-deflated values of the

other variables, based on a log-linearization of equation (2).

(3)

where is the value of domestic shipments of segment in year . represents the percent change in employment in segment from year to year , . , , , and represent the percent changes in the other variables from year to year . The sum of the components on the right-hand side of equation (3) is approximately equal to the percent changes on the left-hand side of equation (3).[10]

Equation (3) is a decomposition of employment changes into changes in the component factors, and in this sense it is a quantification of the contribution of each factor. However, it is not an analysis of causation or a prediction of future effects.[11] The interpretation of the measured contribution of each factor is that it indicates how much employment would change if all other factors remained fixed, while the factor of interest changed by the historical amount.

Estimated Contributions to Changes in Industry Employment

Table

2 reports the contribution of each of the factors to the year-to-year percent

changes in employment in the three segments of the combined U.S. motor vehicle

industry. For each of the contributing factors, the table reports the

percentage change in employment due to the factor, rather than the percentage

change in the factor.

Table 2. Analysis of Average Annual Growth Rates, 1997-2014

|

|

NAICS 3361 Motor Vehicle Manufacturing |

NAICS 336211 Motor Vehicle Body Manufacturing |

NAICS

3363 |

|

U.S. Industry Employment |

-1.4 |

0.3 |

-1.1 |

|

Contributing Factors |

|

|

|

|

U.S. Exports |

1.2 |

0.0 |

0.7 |

|

U.S. Imports |

-2.9 |

0.0 |

-2.2 |

|

Total U.S. Consumption |

4.9 |

2.5 |

4.2 |

|

U.S. Labor Productivity |

-4.4 |

-2.2 |

-4.0 |

Source: USITC calculations. The linear approximation error in these calculations is discussed in note 10.

Overall,

there was a decline in employment in the motor vehicle and parts segments and a

slight increase in employment in motor vehicle body manufacturing. In all three

segments, there were negative contributions to employment associated with increases

in labor productivity and imports, and there were positive contributions to

employment associated with increases in exports and total consumption in the

U.S. market.

According to Table 2, employment in the U.S. motor vehicle manufacturing segment (NAICS 3361) declined by 1.4 percent per year, on average, between 1997 and 2014. The increase in labor productivity would have resulted in a 4.4 percent average reduction in employment if all of the other factors had remained constant, while the increase in U.S. imports would have reduced employment by 2.9 percent. The negative employment effects of these two factors were partly offset by a significant increase in total U.S. consumption and a smaller increase in U.S. exports, for a net 1.4 percent reduction in employment.

On the other hand, employment in the U.S. motor vehicle body manufacturing segment (NAICS 336211) increased by 0.3 percent per year on average. The increase in labor productivity would have resulted in a 2.2 percent average reduction in employment if all of the other factors had remained constant. The increase in total U.S. consumption would have resulted in a 2.5 percent average increase in employment per year more than offsetting the negative effect of the increase in labor productivity, resulting in a net 0.3 percent increase in employment. U.S. imports and exports had a less significant impact on employment.

Finally, employment in the U.S. motor vehicle parts manufacturing segment (NAICS 3363) declined by 1.1 percent per year on average. The increase in labor productivity would have resulted in a 4.0 percent average reduction in employment if all of the other factors had remained constant, and the increase in imports would have reduced employment by an additional 2.2 percent. These two factors were partly offset by the increase in total U.S. consumption and the increase in exports, for a net 1.1 percent reduction in employment.

Conclusions

The

employment changes in the U.S. motor vehicle industry between 1997 and 2014

reflect several trade and non-trade factors: there were negative contributions

from increases in labor productivity and imports and positive contributions

from increases in total consumption and exports. The growth accounting

framework in this research note provides a simple method for quantifying the

relative contributions of these factors using available industry data.[12]

When we split the motor vehicle manufacturing industries into three segments, we find that the relative contributions of the trade and non-trade factors are quite different, and this is ultimately reflected in the different historical changes in employment levels in the segments. While labor productivity and imports contributed to employment declines in motor vehicle and parts manufacturing, there were larger impacts from changes in labor productivity. This is notable since China's accession to the WTO as well as NAFTA and additional U.S. trade agreements were implemented over the time period, which likely accelerated the growth of U.S. imports and exports in these industries. However, trade appeared to play a less significant role in employment declines than the increased use of technology and other factors that increased labor productivity. In all three industries, increased domestic consumption played a larger role than exports in offsetting (partially in motor vehicle and parts manufacturing and completely in body manufacturing) employment reductions that are associated with increases in labor productivity and imports.

References

Boudette, Neal. “Production capacity balloons, but today's industry can support it.” Automotive News, May 18, 2015. https://www.autonews.com/article/20150518/OEM01/305189955/production-capacity-balloons-but-todays-industry-can-support-it.

Coffin, David. Passenger Vehicles. Industry and Trade Summary. Publication ITS-09. Washington, DC: U.S. International Trade Commission, May 2013.

Federal Reserve, G.17 Industrial Product ion and Capacity Utilization, June 15, 2016. https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/G17/default.htm.

International Federation of Robotics. “Industrial Robot Statistics.” 2015. https://www.ifr.org/industrial-robots/statistics/.

Klier, Thomas H. and James Rubenstein. “Detroit back from the brink?” Economic Perspectives, 2Q 2012, 49.

Klier, Thomas, and James Rubenstein. Who Really Makes Your Car? Kalamazoo: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, 2008.

Mercedes Benz U.S. International (MBUSI). “About Mercedes-Benz U.S. International.” https://www.mbusi.com/factory.

Motor & Equipment Manufacturers Association (MEMA). “Restoring Credit to Manufacturers.” Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, Economic Policy Subcommittee, October 9, 2009. https://www.banking.senate.gov/public/?a=Files.Serve&File_id=E4610997-7941-4358-8B4B-1B4C89C7E42C.

Rauwald, Christoph. “BMWs Made in America Surging as Biggest Auto Export.” July 10, 2014. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2014-07-10/bmws-made-in-america-surging-as-biggest-auto-export-cars.

U.S. Bureau of the Census (U.S. Census). “Annual Survey of Manufactures.” Historical Data tables. https://www.census.gov/manufacturing/asm/historical_data (accessed July 1, 2016).

U.S. International Trade Commission (USITC). Interactive Tariff and Trade DataWeb (DataWeb). https://dataweb.usitc.gov (accessed various dates).

U.S. International Trade Commission. Economic Impact of Trade Agreements Implemented Under Trade Authorities Procedures, 2016 Report. Inv. No. 332-555. Publication 4614. June 2016.

Appendix Tables

Table A1. Data for Figure 1

|

Year |

NAICS 3361 Motor Vehicle Manufacturing |

NAICS 336211 Motor Vehicle Body Manufacturing |

NAICS 3363 |

|

1997 |

236,247 |

42,773 |

653,245 |

|

1998 |

234,960 |

43,306 |

789,565 |

|

1999 |

233,053 |

43,170 |

799,174 |

|

2000 |

230,544 |

43,844 |

802,575 |

|

2001 |

213,761 |

41,254 |

732,704 |

|

2002 |

219,243 |

41,450 |

721,655 |

|

2003 |

210,387 |

40,874 |

671,990 |

|

2004 |

215,852 |

43,779 |

644,848 |

|

2005 |

204,065 |

48,342 |

612,872 |

|

2006 |

205,843 |

50,906 |

577,729 |

|

2007 |

179,885 |

49,165 |

580,845 |

|

2008 |

156,251 |

46,002 |

526,672 |

|

2009 |

124,792 |

37,561 |

397,277 |

|

2010 |

137,284 |

35,891 |

388,920 |

|

2011 |

148,009 |

37,665 |

404,636 |

|

2012 |

157,217 |

41,176 |

466,061 |

|

2013 |

166,608 |

41,881 |

483,131 |

|

2014 |

176,001 |

42,917 |

501,065 |

Source: U.S. Census, ASM (accessed July 1, 2016).

Table A2. Data for Figure 2

|

Year |

NAICS 3361 Motor Vehicle Manufacturing |

NAICS 336211 Motor Vehicle Body Manufacturing |

NAICS 3363 |

|

1997 |

95,437,769,729 |

343,174 |

35,276,945,010 |

|

1998 |

102,498,662,613 |

366,237 |

37,899,879,496 |

|

1999 |

122,925,815,555 |

322,635 |

45,603,846,842 |

|

2000 |

132,814,615,371 |

414,446 |

50,000,082,551 |

|

2001 |

130,431,903,687 |

447,466 |

47,098,009,374 |

|

2002 |

136,633,879,892 |

403,039 |

53,700,221,933 |

|

2003 |

137,410,172,910 |

509,193 |

58,505,349,398 |

|

2004 |

145,690,283,994 |

626,834 |

65,292,234,447 |

|

2005 |

148,887,041,680 |

921,513 |

71,603,562,761 |

|

2006 |

162,140,539,954 |

1,019,701 |

72,955,491,912 |

|

2007 |

161,958,491,954 |

997,625 |

75,860,098,408 |

|

2008 |

146,025,142,306 |

822,811 |

67,949,072,917 |

|

2009 |

96,179,426,186 |

592,151 |

48,470,496,097 |

|

2010 |

134,994,259,755 |

661,431 |

70,524,147,403 |

|

2011 |

147,092,793,536 |

743,762 |

81,607,164,827 |

|

2012 |

174,779,220,486 |

955,985 |

94,269,326,731 |

|

2013 |

183,259,646,796 |

754,065 |

97,936,887,818 |

|

2014 |

190,763,845,384 |

783,795 |

106,486,821,687 |

Source: USITC Dataweb (accessed July 12, 2016). Imports for consumption used.

Table A3. Data for Figure 3

|

Year |

NAICS 3361 Motor Vehicle Manufacturing |

NAICS 336211 Motor Vehicle Body Manufacturing |

NAICS 3363 |

|

1997 |

24,290,051,624 |

174,959,105 |

36,230,121,080 |

|

1998 |

22,619,412,870 |

179,323,308 |

36,716,266,188 |

|

1999 |

22,063,782,982 |

212,026,205 |

39,279,833,905 |

|

2000 |

23,022,509,474 |

154,036,319 |

42,288,439,404 |

|

2001 |

22,776,851,427 |

136,410,773 |

39,076,167,258 |

|

2002 |

26,314,058,613 |

109,875,547 |

39,160,015,750 |

|

2003 |

29,658,892,594 |

117,550,769 |

37,281,356,161 |

|

2004 |

30,108,237,085 |

160,398,476 |

39,128,056,532 |

|

2005 |

34,851,026,092 |

197,413,451 |

40,011,521,051 |

|

2006 |

43,829,584,407 |

237,976,908 |

42,739,107,919 |

|

2007 |

52,469,265,443 |

276,249,943 |

44,984,131,886 |

|

2008 |

57,176,246,645 |

192,739,988 |

41,213,374,787 |

|

2009 |

35,856,069,710 |

157,655,516 |

30,074,176,845 |

|

2010 |

48,620,856,753 |

169,252,333 |

41,272,401,607 |

|

2011 |

58,806,191,210 |

235,503,464 |

46,812,312,596 |

|

2012 |

64,860,753,616 |

363,704,168 |

50,878,115,492 |

|

2013 |

69,082,592,413 |

360,700,398 |

51,735,753,594 |

|

2014 |

72,839,507,001 |

451,661,832 |

53,157,860,602 |

Source: USITC Dataweb (accessed July 12, 2016). Domestic exports used.

Table A4. Data for Figure 4

|

Year |

NAICS 3361 Motor Vehicle Manufacturing |

NAICS 336211 Motor Vehicle Body Manufacturing |

NAICS 3363 |

|

1997 |

291,200,575,105 |

9,008,680,215 |

177,558,392,930 |

|

1998 |

309,203,915,743 |

9,696,170,914 |

185,659,644,308 |

|

1999 |

368,262,006,573 |

10,520,423,609 |

209,121,022,937 |

|

2000 |

349,265,461,897 |

10,335,162,410 |

212,047,729,147 |

|

2001 |

327,389,837,260 |

7,660,342,055 |

195,142,004,116 |

|

2002 |

351,019,116,279 |

8,019,082,163 |

219,059,371,183 |

|

2003 |

371,182,198,316 |

8,648,213,642 |

223,517,327,237 |

|

2004 |

377,482,850,909 |

9,437,590,436 |

228,806,123,915 |

|

2005 |

375,879,985,588 |

10,797,334,100 |

237,697,603,710 |

|

2006 |

380,171,013,547 |

11,855,509,724 |

232,515,347,993 |

|

2007 |

368,526,939,511 |

12,350,667,375 |

235,829,570,522 |

|

2008 |

296,927,924,661 |

11,274,819,071 |

202,349,665,130 |

|

2009 |

208,927,369,476 |

9,571,669,495 |

150,814,825,252 |

|

2010 |

293,804,962,002 |

9,637,047,179 |

198,470,063,796 |

|

2011 |

322,072,260,326 |

10,102,314,259 |

219,559,277,231 |

|

2012 |

370,434,487,870 |

11,439,853,281 |

259,114,462,239 |

|

2013 |

397,973,706,706 |

12,181,962,365 |

273,190,160,854 |

|

2014 |

425,235,208,535 |

13,225,048,133 |

297,994,413,573 |

Source: U.S. Census, ASM and U.S. International Trade Commission Dataweb (accessed July 1, 2016). Note: Total consumption is measured as total shipments of the U.S. industry minus U.S. exports plus U.S. imports.

Table A5. Data for Figure 5

|

Year |

NAICS 3361 Motor Vehicle Manufacturing |

NAICS 336211 Motor Vehicle Body Manufacturing |

NAICS 3363 |

|

1997 |

58.112 |

78.671 |

63.985 |

|

1998 |

65.767 |

80.359 |

67.179 |

|

1999 |

71.129 |

82.514 |

70.861 |

|

2000 |

63.845 |

78.043 |

71.969 |

|

2001 |

63.958 |

63.702 |

73.772 |

|

2002 |

72.991 |

73.688 |

83.6 |

|

2003 |

81.872 |

87.959 |

88.213 |

|

2004 |

83.426 |

84.1 |

89.981 |

|

2005 |

87.809 |

88.915 |

94.765 |

|

2006 |

96.781 |

90.853 |

94.052 |

|

2007 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

|

2008 |

89.634 |

92.593 |

95.418 |

|

2009 |

85.019 |

94.633 |

95.736 |

|

2010 |

106.846 |

103.01 |

112.19 |

|

2011 |

114.587 |

103.016 |

113.679 |

|

2012 |

115.951 |

100.59 |

118.032 |

|

2013 |

119.192 |

108.096 |

118.078 |

|

2014 |

113.278 |

107.253 |

122.47 |

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Labor Productivity and Costs Database.