United States International Trade Commission

The Year in Trade 2017

Operation of the Trade Agreements Program

69th Report

August 2018

Publication Number: 4817

United States International Trade Commission

Commissioners

David S. Johanson, Chairman

Irving A. Williamson

Meredith M. Broadbent

Rhonda K. Schmidtlein

Jason E. Kearns

Catherine DeFilippo

Director, Office of Operations

William Powers

Director, Office of Economics

Address all communications to

Secretary to the Commission

United States International Trade Commission

Washington, DC 20436

This report was prepared principally by:

Project Leader

Joanne Guth, Office of Economics

Deputy Project Leader

Tamara Gurevich, Office of Economics

Office of Economics

Justino De La Cruz, Pamela Davis, Stephanie Fortune-Taylor, Alexander Hammer, Lin Jones, Grace Kenneally,

Alissa Tafti, Edward Wilson, and Heather Wickramarachi

Office of General Counsel

William W. Gearhart

Office of Industries

Arthur Chambers, Natalie Hanson, Tamar Khachaturian,

Sarah Oliver, and Laura Rodriguez

Office of Investigations

Brenna Cole, Mary Messer, and Salvatore Mineo

Office of Tariff Affairs and Trade Agreements

Donnette Rimmer and Daniel Shepherdson

Office of Unfair Import Investigations

David Lloyd

Office of Analysis and Research Services

Maureen Letostak, David Lundy, and Laura Thayn

Editorial Review

Judy Edelhoff and Peg Hausman

Statistical Review

Russell Duncan

Content Reviewer

Janis Summers

Administrative Support

Nabil Abbyad and Meryem Demirkaya

Help Desk and Customer Service Division (CIO)

Under the direction of

Arona Butcher, Chief

Country and Regional Analysis Division

Office of Economics

Preface

This report is the 69th in a series of annual reports

submitted to the U.S. Congress under section 163(c) of the Trade Act of 1974

(19 U.S.C. 2213(c)) and its predecessor legislation. Section 163(c) states that

“the International Trade Commission shall submit to the Congress at least once

a year, a factual report on the operation of the trade agreements program.”

This report is one of the principal means by which the U.S.

International Trade Commission provides Congress with factual information on

trade policy and its administration for 2017. The trade agreements program

includes “all activities consisting of, or related to, the administration of

international agreements which primarily concern trade and which are concluded

pursuant to the authority vested in the President by the Constitution” and by

congressional legislation.

+

-

Figure ES.1 U.S. trade balance in goods and services, 2003–17

Figure ES.2 U.S. goods and services trade with major bilateral trading partners, 2017

Figure 1.1 U.S. real gross domestic product, percentage change, 2013–17

Figure 1.2 Economic growth trends in the world, the United States, and major trading partners, 2015–17

Figure 1.3 Indexes of U.S. dollar exchange rates for selected major foreign currencies, daily, 2017

Figure 1.4 U.S. merchandise trade with the world, 2015–17

Figure 1.5 Leading U.S. export markets, by share, 2017

Figure 1.6 Leading U.S. import sources, by share, 2017

Figure 1.7 U.S. cross-border trade in private services with the world, 2015–17

Figure 1.8 Leading U.S. export markets for private services, by share, 2017

Figure 1.9 Leading U.S. import sources for private services, by share, 2017

Figure 2.1 Share of TAA petitions certified by industry sector in FY 2017

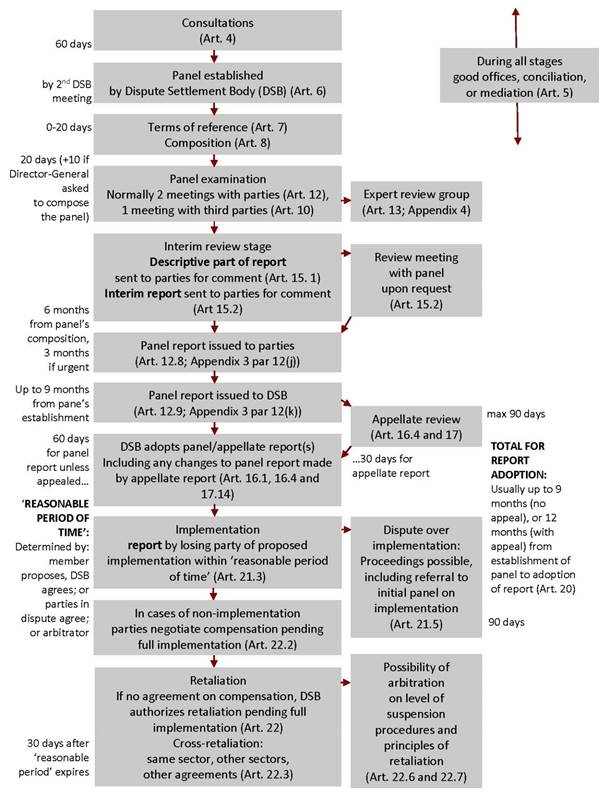

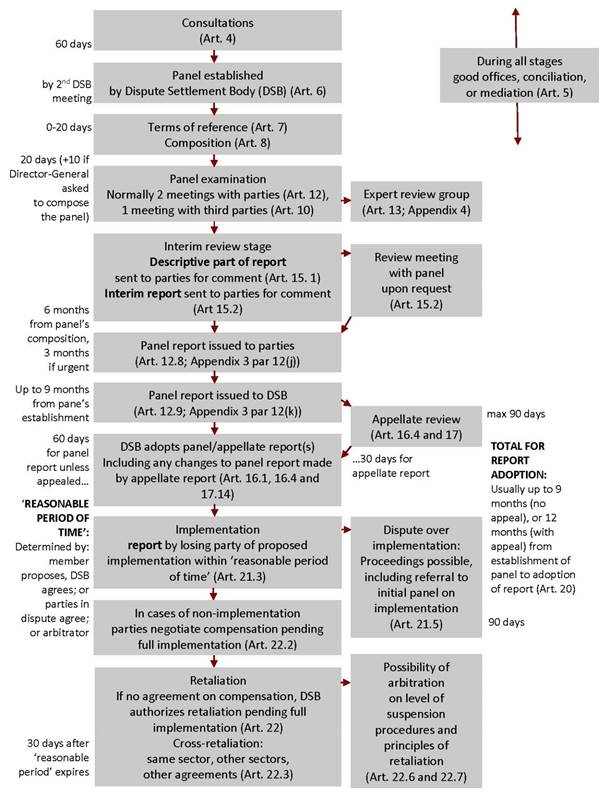

Figure 3.1 Timeline for the WTO Dispute Settlement Process

Figure 6.1 U.S. merchandise trade with the EU, 2013–17

Figure 6.2 U.S. cross-border trade in private services with the EU, 2013–17

Figure 6.3 U.S. merchandise trade with China, 2013–17

Figure 6.4 U.S. cross-border trade in private services with China, 2013–17

Figure 6.5 U.S. merchandise trade with Canada, 2013–17

Figure 6.6 U.S. cross-border trade in private services with Canada, 2013–17

Figure 6.7 U.S. merchandise trade with Mexico, 2013–17

Figure 6.8 U.S. cross-border trade in private services with Mexico, 2013–17

Figure 6.9 U.S. merchandise trade with Japan, 2013–17

Figure 6.10 U.S. cross-border trade in private services with Japan, 2013–17

Figure 6.11 U.S. merchandise trade with South Korea, 2013–17

Figure 6.12 U.S. cross-border trade in private services with South Korea, 2013–17

Figure 6.13 U.S. merchandise trade with India, 2013–17

Figure 6.14 U.S. cross-border trade in private services with India, 2013–17

Figure 6.15 U.S. merchandise trade with Taiwan, 2013–17

Figure 6.16 U.S. cross-border trade in private services with Taiwan, 2013–17

+

-

Table 1.1 U.S. merchandise trade with the world, by USITC digest sector, 2016–17 (million dollars)

Table 1.2 U.S. merchandise trade with major trading partners and the world, 2017 (million dollars)

Table 1.3 U.S. merchandise trade with major trading partners and the world, 2016–17 (million dollars)

Table 1.4 U.S. cross-border trade in private services with major trading partners and the world, 2017 (million dollars)

Table 2.1 Antidumping duty orders that became effective during 2017

Table 2.2 Countervailing duty orders that became effective during 2017

Table 2.3 TAA certifications, by region, FY 2017

Table 2.4 U.S. imports for consumption from Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) beneficiaries, 2015–17

Table 2.5 U.S. imports for consumption from Nepal, 2015–17

Table 2.6 U.S. imports for consumption from AGOA beneficiaries, 2015–17

Table 2.7 U.S. general imports of apparel under AGOA, by country, 2015–17

Table 2.8 U.S. imports for consumption from CBERA/CBTPA beneficiaries, 2015–17

Table 2.9 U.S. imports of apparel from Haiti, 2015–17

Table 3.1 WTO dispute settlement panels established during 2017 in which the United States was a party

Table 3.2 WTO dispute settlement panel and Appellate Body (AB) reports circulated and/or adopted in 2017 in which the United States was a party

Table 4.1 U.S. trade and investment framework agreements in 2017

Table 5.1 Total U.S. exports to FTA partners, by FTA partner, 2015–17

Table 5.2 Total U.S. imports from FTA partners, by FTA partner, 2015–17

Table 5.3 U.S. merchandise trade balance with FTA partners, by FTA partner, 2015–17

Table 5.4 U.S. imports for consumption that entered under FTA provisions, by FTA partner, 2015–17

Table 5.5 Ratio of U.S. imports for consumption under FTAs to U.S. general imports, by partner, 2015–17

Table 5.6 Timetable of major NAFTA negotiations, 2017–18

Table 5.7 Active files as of yearend 2017 under Articles 14 and 15 of the North American Agreement on Environmental Cooperation

Table 5.8 NAFTA Chapter 19 binational panels, active reviews through 2017

Table A.1 U.S. total exports to the world, by USITC digest sector, 2015–17

Table A.2 U.S. general imports from the world, by USITC digest sector, 2015–17

Table A.3 Leading U.S. total exports to the world, by HTS 6-digit subheading, 2015–17

Table A.4 Leading U.S. general imports from the world, by HTS subheading, 2015–17

Table A.5 U.S. merchandise trade with top 15 single-country trading partners, 2017

Table A.6 Top 15 U.S. single-country merchandise export markets, 2017

Table A.7 Top 15 U.S. single-country merchandise import sources, 2017

Table A.8 U.S. private services exports to the world, by category, 2015–17

Table A.9 U.S. private services imports from the world, by category, 2015–17

Table A.10 Antidumping cases active in 2017, by USITC investigation number

Table A.11 Antidumping duty orders and suspension agreements in effect as of December 31, 2017

Table A.12 Countervailing duty cases active in 2017, by USITC investigation number

Table A.13 Countervailing duty orders and suspension agreements in effect as of December 31, 2017

Table A.14 Reviews of existing antidumping and countervailing duty orders and suspended investigations completed in 2017, by date of completion

Table A.15 Section 337 investigations and related proceedings completed by the Commission during 2017 and those pending on December 31, 2017

Table A.16 Outstanding section 337 exclusion orders as of December 31, 2017

Table A.17 U.S. imports for consumption under GSP, by source, 2015–17

Table A.18 Value of U.S. imports for consumption under GSP, by USITC digest sector, 2015–17

Table A.19 Share of U.S. imports for consumption under GSP, by USITC digest sector, 2015–17

Table A.20 Leading U.S. imports for consumption under GSP, by HTS 6-digit subheading, 2015–17

Table A.21 Leading U.S. imports for consumption under AGOA (excluding GSP), by HTS 6-digit subheading, 2015–17

Table A.22 Leading U.S. imports for consumption under AGOA (excluding GSP), by source, 2015–17

Table A.23 Leading U.S. imports for consumption under CBERA, by HTS 6-digit subheading, 2015–17

Table A.24 U.S. imports for consumption under CBERA, by source, 2015–17

Table A.25 WTO dispute settlement cases to which the United States was a party, developments in 2017

Table A.26 NAFTA Chapter 19 substantive challenges to original and five-year review determinations of USITC and USDOC, developments in 2017

Table A.27 U.S. total exports to the EU, by USITC digest sector, 2015–17

Table A.28 U.S. general imports from the EU, by USITC digest sector, 2015–17

Table A.29 Leading U.S. total exports to the EU, by HTS 6-digit subheading, 2015–17

Table A.30 Leading U.S. total imports from the EU, by HTS 6-digit subheading, 2015–17

Table A.31 U.S. total exports to China, by USITC digest sector, 2015–17

Table A.32 U.S. general imports from China, by USITC digest sector, 2015–17

Table A.33 Leading U.S. total exports to China, by HTS 6-digit subheading, 2015–17

Table A.34 Leading U.S. general imports from China, by HTS 6-digit subheading, 2015–17

Table A.35 U.S. total exports to Canada, by USITC digest sector, 2015–17

Table A.36 U.S. general imports from Canada, by USITC digest sector, 2015–17

Table A.37 Leading U.S. total exports to Canada, by HTS 6-digit subheading, 2015–17

Table A.38 Leading U.S. general imports from Canada, by HTS 6-digit subheading, 2015–17

Table A.39 U.S. total exports to Mexico, by USITC digest sector, 2015–17

Table A.40 U.S. general imports from Mexico, by USITC digest sector, 2015–17

Table A.41 Leading U.S. total exports to Mexico, by HTS 6-digit subheading, 2015–17

Table A.42 Leading U.S. general imports from Mexico, by HTS 6-digit subheading, 2015–17

Table A.43 U.S. total exports to Japan, by USITC digest sector, 2015–17

Table A.44 U.S. general imports from Japan, by USITC digest sector, 2015–17

Table A.45 Leading U.S. total exports to Japan, by HTS 6-digit subheading, 2015–17

Table A.46 Leading U.S. total imports from Japan, by HTS 6-digit subheading, 2015–17

Table A.47 U.S. total exports to South Korea, by USITC digest sector, 2015–17

Table A.48 U.S general imports from South Korea, by USITC digest sector, 2015–17/a>

Table A.49 Leading U.S. total exports to South Korea, by HTS 6-digit subheading, 2015–17

Table A.50 Leading U.S. general imports from South Korea, by HTS 6-digit subheading, 2015–17

Table A.51 U.S. total exports to India, by USITC digest sector, 2015–17

Table A.52 U.S. general imports from India, by USITC digest sector, 2015–17

Table A.53 Leading U.S. total exports to India, by HTS 6-digit subheading, 2015–17

Table A.54 Leading U.S. general imports from India, by HTS 6-digit subheading, 2015–17

Table A.55 U.S. total exports to Taiwan, by USITC digest sector, 2015–17

Table A.56 U.S. general imports from Taiwan, by USITC digest sector, 2015–17

Table A.57 Leading U.S. total exports to Taiwan, by HTS 6-digit subheading, 2015–17

Table A.58 Leading U.S. general imports from Taiwan, by HTS 6-digit subheading, 2015–17

Table B.1 U.S. trade balance in goods and services, 2003–17 (million dollars)

Table B.2 U.S. goods and services trade with major bilateral trade partners, 2017 (million dollars)

Table B.3 U.S. real gross domestic product, percentage change, 2013–17

Table B.3 U.S. real gross domestic product, percentage change, 2013–17

Table B.4 Economic (GDP) growth trends in the world, the United States, and major trading partners 2015–17 (percent)

Table B.5 U.S. merchandise trade with major trading partners and the world, 2013–17

Table B.6 U.S. merchandise trade with major trading partners and the world, 2017

Table B.7 U.S. private cross-border services trade with selected major trading partners and the world

Table B.8 U.S. private cross-border services trade with major trading partners and the world, 2017

Table B.9 TAA petitions certified, by industry sector, FY 2017

Abbreviations and Acronyms

|

Acronyms

|

Term

|

|

AGOA

|

African Growth and Opportunity Act

|

|

AIT

|

American Institute in Taiwan

|

|

APEC

|

Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum

|

|

ASEAN

|

Association of Southeast Asian Nations

|

|

ATAP

|

U.S.-Israel Agreement on Trade in Agricultural Products

|

|

BDCs

|

beneficiary developing countries

|

|

BEA

|

Bureau of Economic Analysis (USDOC)

|

|

Brexit

|

Britain’s vote to leave the European Union

|

|

CAFTA-DR

|

Dominican Republic-Central America-United States Free Trade Agreement

|

|

CARICOM

|

Caribbean Community and Common Market

|

|

CBERA

|

Caribbean Basin Economic Recovery Act

|

|

CBP

|

Customs and Border Protection (CBP)

|

|

CBTPA

|

Caribbean Basin Trade Partnership Act

|

|

CEC

|

Commission for Environmental Cooperation (NAFTA)

|

|

CED

|

Comprehensive Economic Dialogue (U.S.-China)

|

|

CITES

|

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora

|

|

CLC

|

Commission for Labor Cooperation (NAFTA)

|

|

CNL

|

competitive need limitation

|

|

COMESA

|

Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa

|

|

CRS

|

Congressional Research Service

|

|

CSPV

|

crystalline silicon photovoltaic (cells)

|

|

CTI

|

Committee on Trade and Investment (APEC)

|

|

CTPA

|

U.S.-Colombia Trade Promotion Agreement

|

|

CVD

|

countervailing duty

|

|

DFAT

|

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (Australia)

|

|

DSB

|

Dispute Settlement Body (WTO)

|

|

ECOWAS

|

Economic Community of West African States

|

|

EDA

|

Economic Development Administration (USDOC)

|

|

EGA

|

Environmental Goods Agreement

|

|

EIA

|

U.S. Energy Information Administration

|

|

EIAP

|

Earned Import Allowance Program

|

|

EIU

|

Economist Intelligence Unit

|

|

ETA

|

Employment and Training Administration (USDOL)

|

|

EU

|

European Union

|

|

FAS

|

Foreign Agricultural Service (USDA)

|

|

FDA

|

Food and Drug Administration

|

|

FDI

|

foreign direct investment

|

|

Fed. Reg.

|

Federal Register

|

|

FMCSA

|

Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration

|

|

FTA

|

free trade agreement

|

|

FTAAP

|

Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific

|

|

FTC

|

Free Trade Commission (under U.S. FTAs)

|

|

FY

|

fiscal year

|

|

GATS

|

General Agreement on Trade in Services

|

|

GATT

|

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade

|

|

GCC

|

Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf (Gulf Cooperation Council)

|

|

GDP

|

gross domestic product

|

|

GMP

|

good manufacturing practice

|

|

GPA

|

Agreement on Government Procurement (WTO)

|

|

GSP

|

Generalized System of Preferences

|

|

GVC

|

global value chain

|

|

HELP

|

Haiti Economic Lift Program

|

|

HOPE

|

Haitian Hemispheric Opportunity through Partnership Encouragement Act

|

|

HTS

|

Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States

|

|

ICSID

|

International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes

|

|

ICT

|

information and communications technology

|

|

ILAB

|

Bureau of International Labor Affairs (USDOL)

|

|

IMF

|

International Monetary Fund

|

|

IP

|

intellectual property

|

|

IPR

|

intellectual property rights

|

|

ITA

|

Information Technology Agreement (WTO)

|

|

JCCT

|

Joint Commission on Commerce and Trade

|

|

KORUS

|

U.S.-Korea Free Trade Agreement

|

|

LDBDC

|

least-developed beneficiary developing country

|

|

LDCs

|

lesser-developed countries

|

|

LTFV

|

less than fair value

|

|

MAFF

|

Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries (Japan)

|

|

MOU

|

memorandum of understanding

|

|

MSMEs

|

micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises

|

|

MRA

|

mutual recognition agreement

|

|

MRL

|

maximum residue limit

|

|

mt

|

metric tons

|

|

n.d.

|

not dated

|

|

NAALC

|

North American Agreement on Labor Cooperation (NAFTA)

|

|

NAFTA

|

North American Free Trade Agreement

|

|

NAO

|

National Administrative Office (NAFTA)

|

|

n.e.s.o.i.

|

not elsewhere specified or included

|

|

n.i.e.

|

not included elsewhere

|

|

NTPA

|

Nepal Trade Preference Act

|

|

NTPP

|

Nepal Trade Preference Program

|

|

NTR

|

normal trade relations (U.S. equivalent to most-favored-nation treatment)

|

|

OECD

|

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

|

|

OIE

|

World Organisation for Animal Health (Office International des Epizooties)

|

|

OPEC

|

Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries

|

|

OTEXA

|

Office of Textiles and Apparel (USDOC)

|

|

PSU

|

Policy Support Unit (APEC)

|

|

PTPA

|

U.S.-Peru Trade Promotion Agreement

|

|

Pub. L.

|

Public Law

|

|

RTA

|

regional trade agreement

|

|

ED

|

Strategic

and Economic Dialogue (U.S.-China)

|

|

SACU

|

Southern Africa Customs Union

|

|

SAT

|

Tax

Administration Service (Mexico)

|

|

SMEs

|

small and medium-sized enterprises

|

|

SPS

|

sanitary

and phytosanitary (standards)

|

|

SSA

|

sub-Saharan Africa

|

|

TAA

|

Trade

Adjustment Assistance

|

|

TAAEA

|

Trade Adjustment Assistance Extension Act

|

|

TAARA

|

Trade

Adjustment Assistance Reauthorization Act of 2015

|

|

TEC

|

Transatlantic Economic Council

|

|

TECRO

|

Taipei

Economic and Cultural Representative Office in the United States

|

|

TICFA

|

Trade and Investment Cooperation Forum Agreement

|

|

TIFA

|

Trade

and Investment Framework Agreement

|

|

TiSA

|

Trade in Services Agreement

|

|

TiVA

|

Trade

in Value Added (OECD–WTO initiative)

|

|

TPA

|

trade promotion agreement

|

|

TPEA

|

Trade

Preferences Extension Act

|

|

TPF

|

U.S.-India Trade Policy Forum

|

|

TPP

|

Trans-Pacific

Partnership

|

|

TPLs

|

tariff preference levels

|

|

TRAs

|

Trade

Readjustment Allowances

|

|

TRIPS

|

Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property

Rights agreement (WTO)

|

|

TRQ

|

tariff-rate

quota

|

|

TTIP

|

Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership

(U.S.-EU)

|

|

UN

|

United

Nations

|

|

U.S.C.

|

U.S. Code

|

|

USCC

|

U.S.-China

Economic and Security Review Commission

|

|

USDA

|

U.S. Department of Agriculture

|

|

USDHS

|

U.S.

Department of Homeland Security

|

|

USDOC

|

U.S. Department of Commerce

|

|

USDOL

|

U.S.

Department of Labor

|

|

USDOS

|

U.S. Department of State

|

|

USDOT

|

U.S.

Department of Transportation

|

|

USITC

|

U.S. International Trade Commission

|

|

USTR

|

U.S.

Trade Representative

|

|

WAEMU

|

West African Economic and Monetary Union

|

|

WTO

|

World

Trade Organization

|

Executive Summary

The level of U.S. imports and U.S. exports of goods and

services depends on many factors, including the strength of the U.S. and global

economies. Growth in these economies contributes to growth in cross-border

trade. The rate of global economic growth increased in 2017, rising from 2.5

percent in 2016 to 3.3 percent in 2017. Economic growth in the United States

also increased in 2017: U.S. real gross domestic product (GDP) grew 2.3 percent

in 2017, compared to an increase of 1.5 percent in 2016. Overall global

economic growth was fueled by growth of advanced economies such as the United

States and top trading partners including the European Union (EU), Canada, and

Japan. Some emerging and developing economies—e.g., China, South Korea, and

Taiwan—also contributed to global economic growth. India and Mexico, however,

grew at a slower rate in 2017 than in 2016.

Both U.S. exports and U.S. imports of goods increased in

value in 2017. The value of U.S. merchandise exports totaled $1,546.7 billion

in 2017, up 6.6 percent ($95.7 billion) from $1,451.0 billion in 2016. The

value of U.S. merchandise imports totaled $2,342.9 billion in 2017, up 7.1

percent ($155.1 billion) from $2,187.8 billion in 2016. The largest increase in

both U.S. imports and U.S. exports was in energy-related products. In

particular, the increase in the value of U.S. imports of crude petroleum was

due to the increase in the price of U.S. crude, whereas the increase in the

value of U.S. exports of crude was driven by increases in both the price and

volume of U.S. crude exports, resulting in a decline in the sector’s deficit to

$4.5 billion. The agricultural sector was the only goods sector to experience a

trade surplus in 2017, with $5.7 billion more in exports than imports. The trade

deficit in the other sectors of the U.S. economy increased. Overall, U.S.

imports increased more than U.S. exports in terms of value, resulting in an

increase in the U.S. merchandise trade deficit from $752.5 billion in 2016 to

$811.2 billion in 2017 (figure ES.1).

U.S. two-way cross-border trade in private services, which

excludes exports and imports of government goods and services n.i.e., increased

5.0 percent to $1,277.7 billion in 2017. U.S. exports of private services grew

3.8 percent to $761.7 billion in 2017, while U.S. imports of private services

grew 6.8 percent to reach $516.0 billion in 2017. As a result, the U.S. surplus

in private services fell from $250.4 billion in 2016 to $245.7 billion in 2017.

Figure

ES.1

U.S. trade balance in

goods and services, 2003–17

Source:

USDOC, BEA, U.S. International Transactions, Services, & IIP, “

Table 1.2: U.S.

International Transactions, Expanded Detail

,” March 21, 2018.

Note:

Underlying data can be found in appendix table

B.1

.

In 2017, the U.S. dollar depreciated 6.3 percent against a

broad trade-weighted index of major foreign currencies, including against some

major emerging-market currencies, such as the Mexican peso and the Chinese

yuan. Between January 1 and December 31, 2017, the U.S. dollar depreciated by

12.0 percent against the euro, 9.4 percent against the United Kingdom (UK)

pound, 6.5 percent against the Chinese yuan, and 6.1 percent against the

Mexican peso.

Key Trade Developments in 2017

Administration of U.S. Trade Laws and Regulations

Safeguard actions:

The U.S. International

Trade Commission (the Commission) conducted two new safeguard investigations

during 2017, both under the global safeguard provisions in sections 201–204 of

the Trade Act of 1974. The first investigation concerned imports of crystalline

silicon photovoltaic cells (CSPV cells); the second, imports of large

residential washers (washers). Both investigations were conducted following

receipt of a petition from a domestic producer of each article. The Commission

made affirmative injury determinations in each investigation and, to address

the serious injury, recommended remedy measures to the President.

Section 301:

There were two ongoing

investigations in 2017 under section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974. The first

investigation was instituted in 1987 and concerned various EU meat hormone

directives, which prohibit the use of certain hormones that promote growth in farm

animals. Following a successful challenge at the World Trade Organization

(WTO), the United States imposed additional duties on certain imports from the

EU in 1999. In 2012, the United States and the EU signed a provisional

settlement, and the United States lifted the additional duties. In December

2016, representatives of the U.S. beef industry filed a request with the Office

of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) asking that the additional duties be

reinstated, and USTR initiated a process to consider whether to reinstate the

additional duties.

The second investigation was self-initiated by the USTR in

August 2017. The investigation is considering whether a wide variety of acts,

policies, and practices by the government of China related to technology transfer,

intellectual property, and innovation are actionable under section 301 of the

1974 Trade Act. Under the statute, USTR generally has up to 12 months from the

date of initiation to determine whether the statutory requirements under

section 301 have been met and, if so, what action to take. The China technology

transfer 301 investigation was ongoing at the end of 2017.

Special 301:

In the

2017 Special 301

Report

, USTR examined the adequacy and effectiveness of intellectual

property rights (IPR) protection in more than 100 countries. The

2017

Special 301 Report

listed 11 countries on the priority watch list

(Algeria, Argentina, Chile, China, India, Indonesia, Kuwait, Russia, Thailand,

Ukraine, and Venezuela) and 23 countries on the watch list. In December 2017,

USTR issued the

2016 Out-of-Cycle Review of Notorious Markets

report

, which highlighted over 25 internet-based

markets and 12 countries with physical marketplaces (e.g., shops) that

reportedly engage in or facilitate substantial copyright piracy and trademark

counterfeiting.

Antidumping duty investigations:

The

Commission instituted 58 new antidumping investigations and made 54 preliminary

determinations and 36 final determinations during 2017. Antidumping duty orders

were issued by the U.S. Department of Commerce (USDOC) in 33 of the final

investigations on 15 products from 16 countries.

Countervailing duty investigations:

The

Commission instituted 26 new countervailing duty investigations, and made 17

preliminary determinations and 16 final determinations during 2017.

Countervailing duty orders were issued by the USDOC in 11 of the final

investigations on 9 products from 5 countries.

Sunset reviews:

During 2017, the Commission

instituted 32 sunset reviews of existing antidumping duty and countervailing

duty orders and suspension agreements that had been in effect for five years,

as required by law. The Commission completed 46 reviews, resulting in the

continuation of 45 antidumping duty and countervailing duty orders for up to

five additional years.

Section 129 investigations:

Section 129 of

the U.S. Uruguay Round Agreements Act established a procedure by which the

Administration may respond to certain adverse WTO panel or Appellate Body

reports. On December 18, 2017, USDOC initiated a section 129 proceeding in

connection with the recommendations and rulings of the WTO Dispute Settlement

Body (DSB) in

United States—Anti-Dumping and Countervailing Measures on

Large Residential Washers from Korea

(DS464). The section 129 proceeding

is expected to be completed in 2018.

Section 337 investigations:

During calendar

year 2017, there were 130 active section 337 investigations and ancillary

proceedings alleging unfair import practices, such as patent infringement.

Seventy-four of these active investigations were instituted in 2017. Of the 74

new proceedings, 59 were new section 337 investigations and 15 were new

ancillary (secondary) proceedings relating to previously concluded

investigations. The Commission completed a total of 64 investigations and

ancillary proceedings under section 337 in 2017, and issued 5 general exclusion

orders, 12 limited exclusion orders, and 30 cease and desist orders.

Commission proceedings in 2017 involved a wide variety of

products. As in prior years, technology products were the single largest

category, with about 38 percent of the active proceedings involving computer

and telecommunications equipment and another 6 percent involving consumer

electronics. In addition, pharmaceuticals and medical devices were at issue in

about 13 percent of the active proceedings and automotive, transportation, and

manufacturing products were at issue in about 10 percent of the active

proceedings.

National Security Investigations:

In April

2017, the U.S. Secretary of Commerce initiated two new investigations under the

national security provisions of section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962,

the first such investigations since 2001. The first investigation concerned

imports of steel and the second concerned imports of aluminum. Both

investigations were in progress at the end of 2017.

Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA):

In

fiscal year (FY) 2017, the U.S. Department of Labor (USDOL) received 1,037

petitions for TAA, down 30.8 percent from the 1,498 petitions received in FY

2016. The USDOL certified 844 petitions covering 94,017 workers as eligible for

TAA, and denied 234 petitions covering 32,038 workers. In FY 2016, the latest

data available, USDOC certified 68 petitions as eligible for assistance under

the TAA for Firms program, and approved 75 adjustment proposals.

Trade Preference Programs

Generalized System of Preferences (GSP):

U.S. imports under GSP increased 11.9 percent, reaching $21.2 billion in 2017.

These imports accounted for 9.9 percent of total U.S. imports from GSP

beneficiary countries and 0.9 percent of total U.S. imports. The top five

beneficiary countries (India, Thailand, Brazil, Indonesia, and Turkey)

accounted for 74.5 percent of GSP imports.

Based on the 2016/2017 GSP Annual Review directed by USTR,

new duty-free status under the GSP program was extended to all GSP

beneficiaries for 23 categories of travel goods (including luggage, backpacks,

handbags, and wallets) that had become eligible for duty-free treatment when

exported by least-developed beneficiary developing countries and African Growth

and Opportunity Act (AGOA) countries in 2016. On December 22, 2017, Argentina’s

GSP eligibility was reinstated after a nearly six-year suspension. Ukraine’s

GSP eligibility was partially removed on December 22, 2017, due to failure to

adequately protect IPRs. Also, in June 2017, USTR self-initiated a country

practice review of Bolivia’s eligibility for GSP benefits because of worker

rights issues.

Nepal Trade Preference Act (NTPA):

The NTPA

was implemented in December 2016 to improve Nepal’s export competitiveness and

help Nepal’s economic recovery following a 2015 earthquake. In 2017, the first

full year that the NTPA was in effect, U.S. imports from Nepal under NTPA were

$2.3 million, accounting for 2.5 percent of total U.S. imports from Nepal.

African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA):

In 2017, 38 sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries were eligible for AGOA

benefits. An additional two countries—The Gambia and Swaziland—were

re-designated as eligible for AGOA benefits effective December 22, 2017,

bringing the total as of yearend 2017 to 40 SSA countries. Of these countries,

27 were also eligible for AGOA textile and apparel benefits for all or part of

2017. Togo, the host of the 16th annual AGOA Forum held on August 8–10, 2017,

became eligible for apparel benefits on August 22, 2017. Also, USTR initiated

an out-of-cycle review of AGOA eligibility for Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda on

June 20, 2017.

In 2017, imports entering the United States exclusively

under AGOA (excluding GSP) were valued at $12.5 billion, a 32.4 percent

increase from 2016. The increase in U.S. imports under AGOA in 2017 can be

attributed to an increase in the value and quantity of imports of crude

petroleum. An additional $1.3 billion from AGOA beneficiary countries entered the

United States duty-free under GSP. In total, AGOA and GSP preference programs

accounted for 55.4 percent of total imports from AGOA beneficiary countries in

2017.

Caribbean Basin Economic Recovery Act (CBERA):

At yearend 2017, 17 countries and dependent territories were eligible for CBERA

preferences, and 8 of those countries were designated eligible for Caribbean

Basin Trade Partnership Act (CBTPA) preferences. In 2017, the value of U.S.

imports under CBERA (including CBTPA) increased by 10.3 percent to $961

million, mainly reflecting an increase in U.S. imports of methanol and

polystyrene from Trinidad and Tobago and The Bahamas, respectively, which are

both major imports under CBERA. U.S. imports under CBERA of crude petroleum

continued to decline as U.S. production increased. Trinidad and Tobago was the

leading supplier of U.S. imports under CBERA in 2017, followed by Haiti.

Haiti initiatives:

While

the

value of U.S. imports of apparel from Haiti increased 2.1 percent to $866.7

million in 2017, the value of such imports entering under the Haitian Hemisphere

Opportunity through Partnership Encouragement Act of 2006 and 2008 (HOPE Acts)

increased 7.9 percent to $577.0 million. The latter accounted for just over

two-thirds of total U.S. apparel imports that entered from Haiti duty-free,

with the remainder entering under CBERA. Garments of manmade fibers accounted

for a growing share of U.S. apparel imports from Haiti, in contrast to the

declining share accounted for by cotton apparel. The main factors in the

overall level of U.S. apparel imports from Haiti are trade preferences under

the HOPE Acts, proximity to the U.S. market, low labor costs, and a recent

infusion of foreign investment in Haiti.

World Trade Organization (WTO)

WTO developments:

The 11th Ministerial Conference of the World Trade Organization was held

December 10–13, 2017, in Buenos Aires, Argentina. As a result of this

conference, the ministers decided to open negotiations on possible disciplines

on fisheries subsidies; WTO members agreed to continue their moratorium on

collecting customs duties on electronic commerce transactions; and members

agreed to continue their moratorium on certain forms of dispute settlement

cases—so-called nonviolation and situation complaints—involving IPRs. While

members agreed at the Ministerial Conference to consider establishing a formal

working group to discuss micro, small, and medium-size enterprises, they were

unable to reach agreement on the issue of public stockholding of foodstuffs for

food security purposes, as well as a number of issues involving ongoing

negotiations in the Doha Development Agenda.

In other WTO developments, WTO membership remained at 164 in

2017, with South Sudan requesting WTO observer status in November 2017. Roberto

Azevêdo was reappointed as WTO Director-General for a second term of four

years, which began in September 2017. On February 22, 2017, the WTO Agreement

on Trade Facilitation entered into force, after ratification by a two-thirds

majority of WTO members. WTO members that participated in the 2012–15

negotiations to expand the so-called WTO Information Technology Agreement

implemented their second set of tariff reductions for over 200 information

technology products on July 1, 2017. Negotiation for an agreement on trade in

environmental goods remained at an impasse in 2017.

WTO dispute settlement:

During 2017, WTO

members filed 17 requests for WTO dispute settlement consultations in new

disputes, which was about the average for the five preceding years. The United

States was the complainant in 3 of the 17 requests filed during 2017, and the

named respondent in 4. Two of the 3 new requests filed by the United States

during 2017 concerned measures maintained by the Canadian province of British

Columbia governing the sale of wine in grocery stores. The third request was related

to subsides paid by China to producers of primary aluminum. The United States

was the named respondent in 4 new disputes—3 filed by Canada on U.S.

countervailing duty and antidumping measures, and 1 filed by Turkey on U.S.

countervailing duty measures.

Four new dispute settlement panels were established during

2017 in which the United States was either the complainant or the respondent.

The United States was the complaining party in two disputes involving China,

and the responding party in two disputes filed by India and Turkey,

respectively.

In the President’s

2018

Trade Policy Agenda and 2017 Annual Report

, the United States summarized

its concerns about the WTO dispute settlement process. In particular, the

report described longstanding concerns that WTO dispute settlement panels and

the Appellate Body have been adding to or diminishing the rights and

obligations of WTO members under the WTO Agreement by not applying the WTO

Agreement as written. The report also described a number of other concerns,

including concerns raised at 2017 WTO Dispute Settlement Body meetings about

service on the Appellate Body by persons who are no longer Appellate Body

members. Since the summer of 2017, U.S. officials have had the view that this

issue must be resolved before the United States will consider supporting new

appointments to the Appellate Body.

OECD, APEC, TiSA, and TIFAs

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and

Development (OECD):

The OECD ministerial council meeting was held in

Paris, France, on June 7–8, 2017. Discussions centered on how to share the

gains from globalization more broadly. In 2017, the OECD Trade Committee

focused its work on broad areas involving trade and the digital economy, as

well as on trade and investment matters. At the September 2016 G20 Summit, the

OECD was tasked by G20 ministers with actively facilitating the work of the

Global Forum on Steel Excess Capacity. November 2017 marked the Global Forum’s

first ministerial meeting

.

Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC)

:

Under Vietnam’s leadership in 2017, cooperation among APEC member economies

focused on “Creating New Dynamism, Fostering a Shared Future.” According to

APEC, this cooperation pursued the following four priorities: “promoting

sustainable, innovative and inclusive growth; deepening regional economic

integration; strengthening micro, small and medium enterprises’ (MSMEs)

competitiveness and innovation in the digital age; and enhancing food security

and sustainable agriculture in response to climate change.”

APEC highlights in 2017 included the completion of three

major reports: two on digital trade and electronic commerce (e-commerce), and

one on the investment climate for global value chains (GVCs). Other important

highlights included (1) projects and a workshop on facilitating MSMEs’ use of

IPRs and promoting MSMEs’ participation in the global economy through GVCs and

e-commerce; (2) case studies on environmental services; and (3) efforts to

advance the realization of the Free Trade Area of the Asia Pacific through

capacity building and an information-sharing mechanism.

Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA):

In

2017, the 23 participants conducted no new rounds of trade negotiations, and as

of the end of 2017, none were scheduled for 2018.

Trade and Investment Framework Agreements (TIFAs)

:

TIFAs provide a framework to expand trade and investment and a forum to resolve

trade and investment issues between the United States and various trading

partners. By yearend 2017, the United States had entered into 57 TIFAs,

including a new TIFA with Paraguay on January 13, 2017. A number of TIFA

Council meetings took place in 2017, including those with Central Asia,

Afghanistan, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Nepal, the Philippines,

Thailand, and Vietnam.

U.S. Free Trade Agreements

U.S. free trade agreements (FTAs) in force in 2017:

The United States was party to 14 FTAs involving a total of 20 countries as of

December 31, 2017. Starting with the most recent agreement, the FTAs in force

during 2017 were Panama (which entered into force in 2012); Colombia (2012);

South Korea (2012); Oman (2009); Peru (2009); several countries of Central

America and the Dominican Republic (CAFTA-DR), which includes the Dominican

Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua (2006–07) and Costa

Rica (2009); Bahrain (2006); Morocco (2006); Australia (2005); Chile (2004);

Singapore (2004); Jordan (2001); Canada and Mexico (1994); and Israel (1985).

FTA merchandise trade flows with FTA partners:

In 2017, total two-way (exports and imports) merchandise trade between the

United States and its 20 FTA partners was $1.5 trillion, which accounted for

39.0 percent of total U.S. merchandise trade with the world. U.S. trade with

the NAFTA countries (Canada and Mexico) continued to contribute the most to all

U.S. trade with FTA partners, accounting for $1.1 trillion, or 75.1 percent.

U.S. exports to the NAFTA countries rose 5.8 percent to $525.4 billion. U.S.

imports from the NAFTA countries rose 7.4 percent to $614.0 billion from 2016

to 2017. As a result, the U.S. merchandise trade deficit with its NAFTA

partners increased by 17.6 percent to $88.6 billion.

U.S. trade with non-NAFTA FTA partners was valued at $378.0

billion in 2017, which was a 3.7 percent increase from 2016. U.S. exports to

these FTA partners increased 8.8 percent to $195.0 billion, while U.S. imports

from these partners increased 3.7 percent to $183.0 billion from 2016 to 2017.

As result, the U.S. merchandise trade surplus with these countries recovered to

its 2015 level, rising 333.9 percent to $12.0 billion in 2017.

The value of imports that entered into the United States

under FTAs and subject to FTA duty reductions and eliminations totaled $385.1

billion in 2017, a rise of 2.8 percent from 2016. Imports subject to FTA duty

reductions and eliminations accounted for nearly half (48.3 percent) of total

imports from FTA partners in 2017 and 16.5 percent of total U.S. imports from

the world. (The majority of U.S. imports from FTA partners that do not enter

under an FTA generally enter free of duty under normal trade relations rates,

although some also face duties.) Imports under the FTA with Chile, which grew

$1.3 billion (26.6 percent), represented the largest percentage increase, while

imports from Mexico accounted for the greatest change in value, rising by $11.9

billion (7.0 percent). Imports under FTAs with Peru and Bahrain also increased

significantly, by 24.5 percent ($651 million) and 16.5 percent ($82 million),

respectively.

FTA negotiations:

In January 2017, the

United States formally withdrew from the recently signed Trans-Pacific

Partnership agreement with 11 Pacific Rim partners. Also in January 2017, U.S.

and EU officials issued a joint report on the status of negotiations towards a

Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP). The report highlighted

areas that still needed “significant work.” No TTIP negotiations were held in

2017.

Developments with FTAs already in force:

U.S. officials met with a number of partners representing member states of the

14 U.S. FTAs in force during 2017. Discussions with U.S. partners focused

largely on the topics of labor issues and environmental provisions included in

most of these agreements. Under the U.S.-Korea FTA, two special sessions of the

Joint Committee were held in 2017 to discuss possible amendments and

modifications to the agreement.

NAFTA developments:

On May 18, 2017, USTR

notified Congress that the President intended to initiate negotiations with

Canada and Mexico to modernize NAFTA. The negotiations began on August 16,

2017, in Washington, DC, with two primary goals: (1) to update NAFTA with

modern provisions on digital trade, intellectual property, cybersecurity, good

regulatory practices, and treatment of state-owned enterprises; and (2) to

rebalance NAFTA and reduce the U.S. trade deficit with Canada and Mexico. By

the end of 2017, five negotiating rounds had been completed.

At the end of 2017, two complaint files remained active

under Articles 14 and 15 of the North American Agreement on Environmental

Cooperation. One, which was submitted in 2016, involved Mexico, and another,

submitted in 2017, involved Canada. In 2017, there were three submissions under

review at the North American Agreement on Labor Cooperation, two involving

Mexico, and one involving the United States.

NAFTA dispute settlement:

In 2017, there

were 5 active Chapter 11 cases (investor-state disputes) filed against the

United States, 4 of them filed by Canadian investors and 1 filed by Mexican

investors; 11 filed by U.S. investors against Canada; and 4 filed against Mexico—3

by U.S. investors and 1 by Canadian investors. At the end of 2017, the NAFTA

Secretariat listed six binational panels active under Chapter 19 (Review and

Dispute Settlement in Anti-dumping and Countervailing Duty Matters); these are

reviews of final determinations made by national authorities in antidumping and

countervailing duty cases. Two of the reviews concern cases filed by the United

States contesting Mexico’s determinations; three concern cases filed by Canada

contesting U.S. determinations; and the sixth concerns a case filed by Mexico

contesting U.S. determinations.

Trade Activities with Major Trading Partners

This report reviews U.S. bilateral trade relations with its

largest trading partners each year. This year, the report covers the following

eight trading partners: the EU, China, Mexico, Canada, Japan, South Korea,

India, and Taiwan (ordered by the value of their two-way merchandise trade).

For each trading partner, the chapter summarizes U.S. bilateral trade,

including two-way merchandise and private services trade (figure ES.2). Each

partner description is followed by summaries of the major bilateral

trade-related developments during 2017.

Figure ES.2

U.S. goods and services

trade with major bilateral trading partners, 2017

Source:

USITC DataWeb/USDOC (accessed April 26, 2018); USDOC, BEA, Interactive data,

International Transactions, Services, & IIP, International Transactions,

Tables 1.2 and 1.3, March 21, 2018 (accessed April 26, 2018).

Note:

Underlying data can be found in appendix table

B.2

.

European Union

The EU as a single entity continued to be the United States’

largest merchandise trading partner in 2017. U.S. two-way (exports plus

imports) merchandise trade with the EU increased 4.7 percent to $718.5 billion

in 2017, accounting for 18.5 percent of total U.S. merchandise trade. U.S.

exports to the EU were $283.5 billion, which ranked the EU as the top U.S.

export market for the second year in a row, surpassing Canada. U.S. merchandise

imports from the EU were $434.9 billion, second to those from China. Both U.S.

exports and U.S. imports with the EU increased in 2017, but U.S. imports grew

more, widening the U.S. merchandise trade deficit with the EU from $146.8

billion in 2016 to $151.4 billion in 2017. Leading U.S. exports to the EU

included civilian aircraft, engines, and parts; medicaments (medicines);

refined petroleum products; crude petroleum; and certain immunological

products. Leading U.S. imports were passenger motor vehicles, medicaments,

parts of turbojets and turbopropellers, light oils, and airplanes and other

aircraft.

The EU was also the United States’ largest trading partner

in terms of private services in 2017, accounting for 33.4 percent of total U.S.

trade in private services. U.S. services imports increased more than U.S.

services exports, shrinking the U.S. trade surplus in services with the EU from

$61.7 billion in 2016 to $49.9 billion in 2017.

Among the important U.S.-EU trade developments in 2017 were

a bilateral agreement on insurance and reinsurance measures, the first annual

review of the functioning of the U.S.-EU Privacy Shield, and an updated mutual

recognition agreement on good manufacturing practices in pharmaceutical

products. Under the framework of the Transatlantic Economic Council, the eighth

workshop for small- and medium-sized enterprises was held. As noted earlier,

TTIP negotiations remained dormant in 2017.

China

In 2017, China remained the United States’ largest single-country

trading partner based on two-way merchandise trade, accounting for 16.4 percent

of total U.S. merchandise trade. U.S. two-way merchandise trade with China

amounted to $635.9 billion in 2017, an increase of 10.0 percent from the $578.2

billion recorded in 2016. The U.S. merchandise trade deficit with China

remained higher than the U.S. trade deficit with any other trading partner in

2017, amounting to $375.2 billion. Its $28.2 billion increase (8.1 percent)

relative to the year before reflected a $42.3 billion increase in U.S.

merchandise imports from China that outpaced a $14.8 billion increase in U.S.

merchandise exports to China in 2017. Leading U.S. exports to China in 2017

were civilian aircraft, engines, and parts; soybeans; small passenger motor

vehicles; petroleum; and semiconductors. Leading U.S. imports from China were

cellphones; portable computers and tablets; telecommunications equipment;

computer parts and accessories; and tricycles, scooters, and related toys.

In 2017, China continued to be the United States’

fourth-largest single-country trading partner based on two-way services trade

of $73.0 billion. U.S. services trade with China amounted to 5.7 percent of

total U.S. cross-border services trade in 2017. The U.S. cross-border trade surplus

in services with China increased $600 million in 2016 to $38.2 billion.

However, the rate of growth in the United States’ services imports from China

outpaced that of the United States’ services exports to China. From 2016 to 2017,

U.S. services exports to China grew by $1.9 billion, or 3.6 percent, while U.S.

services imports from China grew by $1.4 billion, or 8.6 percent.

In 2017, the most prominent bilateral trade issues were

discussed in the context of a newly formed U.S.-China Comprehensive Economic

Dialogue (CED). Major topics addressed by U.S. and Chinese officials in the CED

in 2017 included China’s protection and enforcement of IPRs; Chinese technology

transfer policies and practices; and the implementation of China’s new

Cybersecurity Law and China’s new

Standardization

Law

.

Canada

In 2017, Canada was the United States’ second-largest

single-country trading partner after China for the third consecutive year. The

value of U.S. merchandise trade with Canada rose 7.0 percent to $582.4 billion

in 2017, accounting for 15.0 percent of total U.S. merchandise trade with the

world. Both U.S. merchandise exports and imports with Canada increased in 2017

from the previous year, but imports outpaced exports, resulting in a $6.5

billion increase in the U.S. merchandise trade deficit with Canada to $17.5

billion. Leading U.S. exports to Canada in 2017 included passenger motor

vehicles; motor vehicles for goods transport; civilian aircraft, engines, and

parts; crude petroleum; and light petroleum oils. Top U.S. imports from Canada

included crude petroleum, passenger motor vehicles, natural gas, and coniferous

sawn wood.

Canada remained the second-largest single-country U.S.

trading partner for services in 2017, after the United Kingdom. Two-way

services trade with Canada grew in 2017 to $90.8 billion, while the U.S.

surplus in services increased to $25.8 billion, up from $23.8 billion the year

before.

In 2017, a major focus of U.S.-Canada trade relations was

the renegotiation of NAFTA, which began on August 16, 2017. In addition,

lacking a successor agreement to replace the U.S.-Canada Agreement on Softwood

Lumber—which expired in October 2015—the United States initiated antidumping

and countervailing duty investigations on certain U.S. imports of softwood

lumber from Canada in 2017. In response, Canada initiated dispute settlement

proceedings against the United States in the WTO and NAFTA. In other

developments, the Canada-United States Regulatory Cooperation Council continued

to meet in 2017 to address regulatory issues that hinder cross-border trade and

investment.

Mexico

In 2017, Mexico was the United States’ third-largest

single-country two-way merchandise trading partner. Total two-way merchandise

trade increased 6.4 percent to $557.0 billion in 2017, which accounted for 14.3

percent of U.S. trade with the world. U.S. merchandise exports to Mexico

totaled $243.0 billion in 2017, and U.S. merchandise imports from Mexico

totaled $314.0 billion. The resulting merchandise trade deficit of $71.0

billion was up $6.7 billion from 2016. In 2017, leading U.S. exports to Mexico

were light oils; computer parts and accessories; refined petroleum products;

processors and controllers; and internal combustion diesel engines. Leading

U.S. imports from Mexico included passenger motor vehicles; computers; motor

vehicles for goods transport; crude petroleum; telecommunications equipment;

and color TV reception apparatus.

Mexico was the United States’ sixth-largest trading partner

in services after Germany. U.S. services exports to Mexico increased 3.9

percent ($1.2 billion) and imports from Mexico increased 7.0 percent ($1.7

billion) in 2017, resulting in a narrowing of the U.S. services trade surplus

with Mexico to $6.6 billion in 2017.

A major focus of U.S.-Mexico trade relations in 2017 was the

renegotiation of NAFTA. Joint efforts to modernize border procedures and

facilities also continued in 2017. After the successful conclusion of a pilot

program to address cross-border trucking between the United States and Mexico

under NAFTA, the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) started

accepting applications from Mexico-domiciled motor carriers interested in

conducting long-haul operations beyond the U.S. commercial zones. In 2017,

reports from the FMCSA showed that the safety records of Mexican-owned or

Mexico-domiciled motor carriers surpassed those of U.S. carriers.

Japan

In 2017, Japan remained the United States’ fourth-largest

single-country trading partner in terms of two-way trade, accounting for 5.3

percent of total U.S. merchandise trade. The value of U.S. merchandise trade

with Japan grew 4.6 percent, from $195.3 billion in 2016 to $204.2 billion in

2017. At the same time, the U.S. merchandise trade deficit with Japan was fairly

stable, rising by $38 million in 2017 to $68.8 billion, as U.S. imports

increased more than U.S. exports. Leading U.S. exports to Japan were civilian

aircraft, engines, and parts; liquefied propane; corn; semiconductor

manufacturing machines; and medicaments. Leading U.S. imports from Japan were

passenger motor vehicles, parts for airplanes or helicopters, motor vehicle

gearboxes, and parts for printers.

In 2017, Japan was once again the United States’

third-largest single-country trading partner based on two-way services trade.

U.S. services exports to Japan rose by $1.9 billion, or 4.2 percent, to $45.4

billion in 2017, while U.S. services imports from Japan rose by $1.2 billion,

or 3.0 percent, to $27.5 billion. As a result, the U.S. surplus in services

trade with Japan grew to $17.1 billion from $16.0 billion the year before.

Economic dialogue between the United States and Japan in

2017 focused on a variety of trade issues, including agricultural trade

developments and the efficiency of the Japanese regulatory review process for

medical devices and pharmaceuticals. According to USTR, one of the

Administration’s top trade policy goals was to resolve Japanese import barriers

for U.S. lamb, beef, horticultural products, and processed foods.

Republic of Korea

The Republic of Korea (South Korea) continued to be the

United States’ sixth-largest single-country merchandise trading partner in

2017, accounting for 3.1 percent of U.S. trade with the world. Two-way

merchandise trade was valued at $119.4 billion, up from $112.2 billion in 2016.

U.S. merchandise exports to South Korea were valued at $48.3 billion in 2017,

while U.S. merchandise imports from South Korea totaled $71.2 billion. This resulted

in a trade deficit with South Korea of $22.9 billion in 2017, down 17.0 percent

from 2016. Leading U.S. exports to South Korea included machines for

semiconductor or integrated circuit manufacturing; civilian aircraft, engines,

and parts; processors or controllers; passenger motor vehicles; and crude

petroleum. Leading U.S. imports from South Korea included passenger motor

vehicles, cellphones, computer parts and accessories, refined petroleum

products, and microchips.

In 2017, South Korea became the United States’ 9th-largest

single-country services trading partner based on two-way trade, up from 10th-largest

in 2016. U.S. services exports to South Korea increased 10.0 percent in 2017 to

reach a new high of $22.8 billion. U.S. services imports from South Korea also

increased in 2017, by 7.2 percent, to reach $9.4 billion. Because U.S. services

exports grew more than U.S. services imports, the U.S. services trade surplus

with South Korea increased by 12.0 percent, from $12.0 billion in 2016 to $13.4

billion in 2017.

In 2017, U.S. trade relations with South Korea occurred

within the framework of the U.S.-Korea FTA, which entered into force on March

15, 2012. The United States and South Korea held two special sessions of the

Joint Committee in 2017 to discuss possible amendments or modifications to the

agreement, and in December 2017, it was announced that negotiations would begin

in January 2018.

India

In 2017, India was the United States’ ninth-largest

single-country trading partner based on two-way merchandise trade, maintaining

this position since 2016. U.S. two-way merchandise trade with India increased

by 9.8 percent to $74.3 billion in 2017, accounting for 1.9 percent of U.S.

merchandise trade with the world, the same as in 2016. U.S. merchandise exports

to India were $25.7 billion in 2017 and U.S. merchandise imports from India

were $48.6 billion, resulting in a U.S. merchandise trade deficit with India of

$22.9 billion in 2017, down from $24.3 billion in 2016. Leading U.S. exports to

India in 2017 were nonindustrial diamonds; nonmonetary gold; civilian aircraft,

engines, and parts; bituminous coal; and almonds. Leading U.S. imports from

India in 2017 were nonindustrial diamonds, certain medicaments, frozen shrimp,

light oils, and gold jewelry.

India was the United States’ seventh-largest single-country trading

partner for services and was the only country among the top ten services trading

partners with which the United States had a services trade deficit in 2017. The

services trade deficit with India increased 5.3 percent to $5.8 billion in

2017.

In 2017, the U.S. Trade Representative and the Minister of

Commerce and Industry of India met for the 11th meeting of the India and the

United States Trade Policy Forum, where a wide variety of topics were

addressed. IPR protection remained one of the top bilateral trade issues

between the two countries in 2017.

Taiwan

In 2017, Taiwan became the United States’ 11th-largest

single-country trading partner, dropping from the 10th position in 2016. U.S.

two-way merchandise trade with Taiwan increased 4.5 percent to $68.2 billion

from $65.2 billion in 2016, continuing to account for 1.8 percent of the United

States’ total merchandise trade with the world. The U.S. merchandise trade

deficit with Taiwan in 2017 was $16.7 billion, a 26.7 percent increase from its

2016 trade deficit of $13.2 billion. The top U.S. exports to Taiwan in 2017

were civilian aircraft, engines, and parts; machines for semiconductor or

integrated circuit manufacturing; processors or controllers; computer memories;

and machines for semiconductor boules or wafer manufacturing. The top U.S.

imports from Taiwan were microchips; telecommunications equipment; processors

or controllers; computer parts and accessories; and portable computers and

tablets.

U.S.-Taiwan two-way services trade fell 8.8 percent to $17.2

billion in 2017, accounting for 1.4 percent of all U.S. services trade. U.S.

services exports to Taiwan fell by 18.4 percent to $9.2 billion, while imports

rose 5.5 percent to $8.1 billion, resulting in a 68.6 percent decline in the

U.S. services trade surplus with Taiwan to $1.1 billion in 2017. The drop in

U.S. services exports to Taiwan was due to a reduction in charges for the use

of intellectual property and maintenance and repair services.

The primary forum for bilateral discussions on trade and

investment issues is the U.S.-Taiwan Trade and Investment Framework Agreement

(TIFA). While there was no TIFA Council meeting in 2017, U.S. and Taiwan

officials followed up on issues raised in the 2016 TIFA Council meeting. The

main issues under discussion remained IPRs, agriculture, medical devices, and

pharmaceuticals.

Top of the page

This report provides factual information on the operation of

the U.S. trade agreements program and its administration for calendar year

2017. Section 163(c) of the Trade Act of 1974 (19 U.S.C. 2213(c)) states that

“the International Trade Commission shall submit to the Congress at least once

a year, a factual report on the operation of the trade agreements program.”

Section 1 of Executive Order 11846 defines the trade agreements program to include

“all activities consisting of, or related to, the negotiation or administration

of international agreements which primarily concern trade,”

and section 163(a) of the Trade Act of 1974 sets out the types of information

that the President is to include in his annual report to the Congress on the

operation of the trade agreements program.

This report seeks to provide information on the activities defined in the

Executive Order and, to the extent appropriate and to the extent that there

were developments to report and information was publicly available, the

elements set out in section 163(a).

This first chapter gives an overview of the international

economic and trade environment within which U.S. trade policy was conducted in

2017. It also provides a timeline of selected key trade activities. Chapter 2

covers the administration of U.S. trade laws and regulations in 2017, including

tariff preference programs such as the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP).

Chapter 3 focuses on U.S. participation in the World Trade Organization (WTO),

including developments in major WTO dispute settlement cases during 2017.

Chapter 4 covers 2017 developments at the Organisation for Economic

Co-operation and Development (OECD) and Asian-Pacific Economic Cooperation

(APEC), as well as negotiations on an agreement on trade in services and

developments with trade and investment framework agreements. Chapter 5

describes U.S. negotiation of and participation in free trade agreements (FTAs)

in 2017, and chapter 6 covers trade data and trade relations in 2017 with

selected U.S. trading partners.

This report is based on primary-source materials about U.S.

trade programs and administrative actions pertaining to them. These materials

chiefly encompass U.S. government reports,

Federal Register

notices,

and news releases, including publications and news releases by the U.S.

International Trade Commission (USITC or the Commission) and the Office of the

United States Trade Representative (USTR). Other primary sources of information

include publications of international institutions, such as the International

Monetary Fund, World Bank, OECD, WTO, United Nations, and foreign governments.

When primary-source information is unavailable, the report draws on

professional journals, trade publications, and news reports for supplemental

factual information.

Like past reports,

The Year in Trade 2017

relies on

data from the U.S. Census Bureau (U.S. Census) of the U.S. Department of

Commerce (USDOC) for the U.S. merchandise trade statistics presented throughout

the report. Most tables in the report present U.S. merchandise trade statistics

using “total exports” and “general imports” as measures,

except for data on imports that have entered the United States with a claim of

eligibility under trade preference programs and FTAs. Such data require an

analysis of U.S. “imports for consumption”—goods that have been cleared by U.S.

Customs and Border Protection to enter the customs territory of the United

States with required duties paid.

Also, much of the trade data used in the report, including U.S. services and

merchandise trade data, are revised over time, so earlier years’ trade

statistics in this report may not always match the data presented in previous

reports. Most of the merchandise trade data used in this report can be accessed

using the USITC’s DataWeb database (

https://dataweb.usitc.gov

).

Chapters 1 and 6 also offer data on services trade. The

information on services trade is based on data for cross-border trade in

private services, which exclude government sales and purchases of goods and services

not included elsewhere. The source of these data is the Bureau of Economic

Analysis (BEA) of the USDOC.

The level of U.S. imports and

exports of goods and services depends on many factors, including the strength

of the U.S. and global economies. The United States had a $19.4 trillion

economy in 2017.

The U.S. economy grew faster in 2017 than in 2016: U.S. real gross domestic

product (GDP) increased 2.3 percent in 2017, compared to the growth rate of 1.5

percent in 2016 (figure 1.1).

The largest factors behind the higher growth rate were the following four

industries: professional and business services; finance, insurance, real

estate, rental, and leasing; manufacturing; and retail trade.

Figure

1.1

U.S. real gross domestic product, percentage

change, 2013–17

Source:

USDOC, BEA,

“

Real Gross Domestic

Product

,” March 26, 2018.

Note:

Underlying data can be found in appendix table

B.3

.

The global economic growth rate rose from 2.5 percent in

2016 to 3.3 percent in 2017 (figure 1.2).

The advanced economies grew faster in 2017 than in 2016. The change in the

growth rate of emerging and developing economies was small—0.1 percentage point

from 2016 to 2017—and was primarily due to the relatively unchanged high rate

of growth of the Chinese economy. Among the United States’ top eight trading

partners, only India and Mexico showed slower growth rates in 2017 than in 2016

(figure 1.2).

Figure

1.2

Economic growth trends in the world, the

United States, and major trading partners, 2015–17

Source:

IMF,

World Economic Outlook

, October

2017 (accessed March 26, 2018).

Note:

Underlying data can be found in appendix table

B.4

.

Worldwide growth can be attributed to the strengthening of

domestic demand in advanced economies and in China. Canada showed one of the

larger improvements in terms of growth, doubling its real GDP growth rate from

1.5 percent in 2016 to 3.0 percent in 2017 due to increased domestic demand.

On the other hand, India’s growth rate slowed down, decreasing from 7.1 percent

in 2016 to 6.7 percent in 2017. This was attributed to changes in government

policies, such as the introduction of a goods and services tax, as well as a

currency exchange initiative.

South Korea’s economy continued to grow modestly, increasing its growth rate

from 2.8 percent in 2016 to 3.0 percent in 2017. Despite this increase, South

Korea’s rate of growth was below the world average in 2017.

Overall world trade volume for goods and services increased

by 4.2 percent in 2017, compared to a 2.4 percent increase in 2016.

Both advanced and emerging economies showed increased growth rates in imports

and exports in 2017, but emerging economies’ trade flows grew at a higher rate.

In 2017, exports from emerging economies grew 4.8 percent, up from 2.5 percent

in 2016. This is compared to 3.8 percent for advanced economies, up from 2.2

percent in 2016. Imports grew by 4.4 percent, up from 2.0 percent, in emerging

economies, and by 4.0 percent, up from 2.7 percent, in advanced economies over

the same period.

The U.S. dollar depreciated relative to the broad dollar

index, falling 6.3 percent between January and December of 2017.

[16]

This trend was driven by the depreciation of the U.S. dollar against major

world currencies (figure 1.3). Between January 1 and December 31, 2017, the

U.S. dollar depreciated by 12.0 percent against the euro; 9.4 percent against

the United Kingdom (UK) pound; 6.8 percent against the Canadian dollar; 6.6

percent against the Indian rupee; 6.5 percent against the Chinese yuan; 6.1

percent against the Mexican peso; and 4.2 percent against the Japanese yen.

[17]

Figure

1.3

Indexes of U.S. dollar exchange rates for

selected major foreign currencies, daily, 2017

Source:

Federal Reserve System, “

Foreign Exchange Rates

” (accessed March 26, 2018).

Note:

This figure shows the units of the foreign currency per unit of the U.S.

dollar. A decrease in the index represents a depreciation of the U.S. dollar

relative to the foreign currency, and an increase in the index represents an

appreciation of the U.S. dollar relative to the foreign currency.

The depreciation of the dollar was partly driven by changes

in the economic performance of major U.S. trading partners. As reported by some

major U.S. investment banks, during 2017 the euro and pound were recovering

from an earlier drop caused by uncertainty over the Brexit vote. At the same

time, the German and French economies were experiencing increased growth. These

factors boosted demand for the euro among global investors. On the other hand,

2017 was a year of uncertainty over the current monetary and trade policy of

the United States. This uncertainty led to a reduction in demand for the U.S.

dollar, causing depreciation of the U.S. dollar relative to other major foreign

currencies.

[18]

The broad fall of the U.S. dollar in 2017 contrasts with its mixed performance

against major currencies in 2016.

[19]

The value of U.S. merchandise exports was $1,546.7 billion

in 2017, a 6.6 percent increase from the 2016 level (figure 1.4 and appendix

table A.1). U.S. merchandise imports totaled $2,342.9 billion over the same period,

a 7.1 percent increase from the 2016 level (figure 1.4 and appendix table A.2).

U.S. imports increased more than U.S. exports, leading to a $59.4 billion

increase in the U.S. merchandise trade deficit to $796.2 million in 2017.

The agricultural sector was the only sector that experienced a trade surplus in

2017, exporting $5.7 billion in agricultural products in excess of imports.

Figure

1.4

U.S. merchandise trade with the world,

2015–17

Source:

USITC DataWeb/USDOC (accessed March 14, 2018).

Note:

Underlying data can be found in appendix table

B.5

.

Energy-related products had the largest absolute and

relative (percentage) increase in imports and exports: exports rose 45.5

percent in 2017, and imports increased by 25.5 percent over the same period